PG&E;’s Recovery Stifles Oversight

For us Southern Californians, the one saving grace about Pacific Gas & Electric Co.’s performance as a utility company and a corporate neighbor has long been this: It’s not our problem.

Because its service area is limited to the northern and central parts of the state, we could afford to watch with amused detachment in 2001 when Robert Glynn, the chairman and chief executive of parent company PG&E; Corp., truculently threw the utility into bankruptcy protection at the height of the energy crisis instead of trying to negotiate a solution with then-Gov. Gray Davis. Would the move threaten power supplies or lead to higher bills? That was of merely academic concern to ratepayers at this end of California.

But now it’s time for the rest of us to get worried.

PG&E;’s plan to emerge from bankruptcy protection Monday is based on a reorganization agreement that will undermine the authority of California regulators for years to come. It includes a commitment by the Public Utilities Commission to help the company acquire an investment-grade credit rating, a role that government agencies arguably shouldn’t accept as their responsibility. It allows PG&E; to appeal certain PUC actions to federal courts, which normally don’t have jurisdiction over the commission.

Finally, it includes a customer-financed bailout of as much as $9 billion -- so lavish that consumer advocates worry that it could provide other troubled utilities with the incentive to declare bankruptcy themselves.

“The bankruptcy was an abomination, the worst abuse of the process by a solvent company that I’m aware of,” says Bob Finkelstein, executive director of San Francisco-based TURN, The Utility Reform Network. “But it worked out just as PG&E; wanted.”

Regardless of the troubling precedents in the plan, the PUC signed off on it in a 3-2 vote in December. The Bankruptcy Court did the same a few weeks later. Even TURN capitulated, conceding that the terms were “a fact of life.” At this moment, the only obstacle to PG&E;’s implementing the plan on schedule is a hearing Friday before a federal judge, who has been asked by the two PUC commissioners in opposition, Loretta Lynch and Carl Wood, to suspend the process until the judge can determine whether the plan’s terms violate state law. San Francisco and Palo Alto city officials, meanwhile, will be asking a state appeals court to overturn the PUC’s approval, but their motion won’t even be formally filed until April 15.

What’s extraordinary about this outcome is that the reorganization leaves PG&E; investors almost unaffected by the bankruptcy proceedings. In a normal Chapter 11 case, investors get eviscerated. Bondholders receive pennies on the dollar, and shareholders end up, at best, with a tiny fraction of the ownership they started with.

Not here. PG&E; bondholders are going to be repaid all interest and principal due. Shareholders similarly will be made whole, with owners of preferred stock receiving all $82 million of their accrued dividends immediately. PG&E; expects to restore the dividend on common shares by mid-2005.

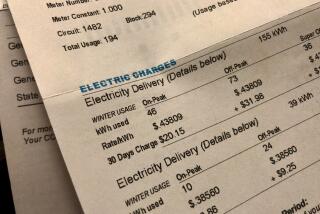

No prize for guessing who loses. The money for these handouts will come out of the customers’ hides, through artificially elevated electricity and gas rates. PG&E; sugar-coated the plan by announcing a rate cut, but its size isn’t anywhere near what has been implemented by Southern California Edison, which somehow stayed out of bankruptcy during the crisis.

More relevant for non-PG&E; customers is the way the plan will stifle the PUC. The commission will be prevented from imposing on PG&E; the thorough oversight it exercises over other utilities, which have to justify their financial decisions to the PUC every year. If they’ve overpaid their executives, made a dumb financing deal, or otherwise failed to run a tight ship, they face the risk that the commission will disallow the resulting costs and stick shareholders, not customers, with the bill.

But the bankruptcy settlement exempts a portion of PG&E;’s rates -- exactly how much is a matter of debate -- from this oversight. To start with, the settlement gives the utility a special handout, known as a “regulatory asset,” of $2.2 billion, to be extracted from customer rates without any adjustment by the PUC.

The deal further grants PG&E; a guaranteed minimum return on equity, the key rate-making benchmark, of 11.22% for as long as nine years. Normally, this figure would decline as the utility’s financial performance improved; a lower return tends to mean lower rates. But because the PUC will be locked into this minimum, its rate-making flexibility will be necessarily constrained.

Also exempted from PUC oversight is the company’s recent $6.7-billion bond issue, which was floated to improve the utility’s financial footing. The cost, including the interest charged and fees for PG&E;’s investment bankers, is fully recoverable from gas and electric customers “without further review” by the commission. That’s an unusual provision in utility finance, experts say, especially where no other independent check on the financing terms exists. New Jersey and Texas, for example, mandate that both the utility and an independent advisor formally certify that any similar “no further review” bonds have been issued at the most advantageous price for ratepayers.

By some accounts, the absence of such review in PG&E;’s case may have cost ratepayers as much as $100 million when the bonds were floated last month. Even before the issue was completed, market experts say, the bonds started selling for more than the offering price -- a signal that the underwriters underestimated demand and sold them cheap. But as long as PG&E; figured it would recover the financing cost from customers no matter what, why should anyone care?

This is not to blame PG&E; for instinctively trying to protect its investors at its customers’ expense; it’s as natural as it is for a cat to acquire a hairball. For all the grumbling that greeted the disclosure a few months back that Chairman Glynn would be receiving a $17-million bonus for his great work in shepherding the utility out of bankruptcy, one must acknowledge that his shareholders have made out like bandits.

But what’s the PUC’s excuse? In defending the bankruptcy settlement, the commission majority wrote at length of the need to dress up PG&E; as an investment-grade credit, like Eliza Doolittle getting primped for Ascot. The mystery is why customers should bear the entire $9-billion expense of this process.

Why not recapitalize the company by issuing a few billion dollars in new stock, for example, forcing existing shareholders to suffer a commensurate shearing? Why not shave a few hundred million off the money due bondholders? Why not impose a series of financial strictures, including limitations on executive compensation, and ensure that the money saved goes into cutting rates?

One can argue that to take any of those steps would impair the company’s investment standing, raise its capital costs, and therefore cost customers money. But the truth is that the most damaging step was Glynn’s decision to declare bankruptcy. It was obvious in April 2001, when the filing was made, and it’s obvious today that this was by no means financially necessary. Glynn’s goal, instead, was to extricate PG&E; from as much state oversight as he could manage. That he succeeded so well can only be a signal to his fellow utility magnates that the system can be conned.

Golden State appears every Monday and Thursday. You can reach Michael Hiltzik at golden.state@latimes.com and read his previous columns at latimes.com/hiltzik.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.