King Children Divided Over Fate of Center

ATLANTA — Every year since the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., his widow, Coretta Scott King, has marked his birthday at the church where he delivered his first and last sermon.

But this year, no one at Ebenezer Baptist Church is sure Coretta King -- or any of her four children -- will attend Monday.

As Coretta King, 78, has spent the last few months recuperating from a major stroke that left her unable to speak, her children have been embroiled in a bitter squabble over the fate of the struggling King Center, which their mother founded shortly after her husband’s death.

Just steps away from the church where King preached his gospel of nonviolence, his children have hired locksmiths to keep each other out of the center, and have shared their grievances with local media.

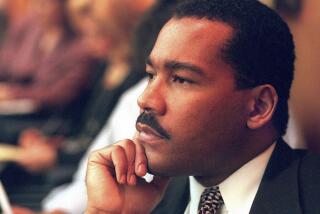

While Dexter Scott King and Yolanda Denise King are pushing efforts to sell the Atlanta landmark -- which needs an estimated $11.6 million in repairs -- to the National Park Service, their siblings, Martin Luther King III and Bernice Albertine King, are opposing the sale.

“Bernice and I stand to differ with those who would sell our father’s legacy and barter our mother’s vision, whether it is for 30 pieces of silver or $30 million,” Martin King said at a news conference last month.

The spectacle of King’s children squabbling over their father’s legacy has embarrassed many of Atlanta’s civil rights activists, who have spent months preparing for what would have been King’s 77th birthday.

“Its petty, really petty,” said Pamela Orange, 25, who spent last week coordinating the Martin Luther King March Committee after her father, the Rev. James Orange, the committee’s chairperson, fell ill.

Orange -- whose father was a member of King’s staff -- is disappointed that the King children do not do more to promote their father’s teachings, but she also worried that they received too much scrutiny.

“I know how hard it can be,” she said. “Not everyone wants to follow their father’s footsteps.”

While King’s children were not readily available for comment, other members of the family downplayed the significance of the feud.

“If this was the Jones family or the Smith family, no one would pay attention,” said Alveda C. King, 54, the daughter of King’s brother, the Rev. Alfred Daniel King, who said her own children locked each other out of their rooms and then happily tossed balls together the next day. “Of course, this happens to be a bigger building called the King Center,” she said. “But you can expect those four to go on and promote their father.”

Yet up and down Auburn Avenue -- where King was born, and where he, his father and his grandfather served as pastors of Ebenezer Baptist Church -- there is growing concern about who will continue King’s mission against poverty, racism and war.

The Rev. Joseph Lowery, one of King’s most trusted lieutenants, said that everyone within the civil rights community was concerned about how the conflict in the King family might affect Coretta King’s health.

“Dr. King’s legacy is not deposited in Coretta or his children or in the brick and mortar of the center,” Lowery said. “It’s in the hearts and minds of people who celebrate his birthday.”

The King Center is not the only struggling civil rights institution in Atlanta. A couple of blocks away, the once renowned Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was co-founded by King and led the battle against segregation in the 1960s, has recently suffered from leadership squabbles and financial difficulties.

“We’re watching the changing of the guard,” said Wellington Howard, who founded Georgia Insurance Brokerage on Auburn Avenue 36 years ago. “There are no leaders like King and [the Rev. Ralph David] Abernathy and Lowery anymore.”

Soon after Dexter King succeeded his mother as head of the King center in 1989, Howard said, the family’s standing in the Sweet Auburn neighborhood dropped.

“Coretta was not quite a saint, but she had a lot of hopes and dreams,” he said. “The kids have only used their daddy’s image to make money.”

Dexter and Martin King have drawn considerable criticism from the community for drawing six-figure salaries from the King Center, while reducing programs and allowing its buildings to fall into disrepair.

When Coretta King founded the center in the basement of her home shortly after her husband was assassinated in 1968, she envisaged that it would play a leading role in furthering the Rev. King’s vision of social change.

By 1981, she had raised $8 million to build on Auburn Avenue, and invited a wide selection of notable African Americans -- including author James Baldwin and actor Sidney Poitier -- to serve on the board.

Now only nine board members remain. All are family members, except former U.N. Ambassador Andrew Young, who was a close colleague of King’s.

The National Park Service has estimated that the nearly 25-year-old Auburn Avenue complex -- which includes an exhibition hall, an archives building, and King’s marble tomb, which sits on top of a reflective pool -- is in need of $11.6 million in repairs. The reflective pool leaks, drainage pipes have collapsed and wiring is loose and exposed.

Perhaps most significantly, the center -- whose mission statement declares its dedication to “developing and disseminating programs that educate the world about Dr. King’s philosophy and methods of nonviolence” -- no longer offers programs on nonviolence.

“Nothing happens at the center anymore,” said William “Sonny” Walker, a former King Center board member and interim executive director of the center from 1993 to 1995. During that time, he said, the center sent staff to South Africa to monitor the 1994 elections and developed school curriculums around King’s teaching.

According to Walker, the family’s mismanagement means that the King Center is no longer an institution that people want to support.

“All four of those King offspring ought to say: ‘What would Daddy do?’ ” he said. “If they did that, I just happen to think they would come together.”

Others insist that the community should not look to the Kings to solve the King Center’s struggle.

For Georgia Rep. Tyrone Brooks, president of the Georgia Assn. of Black Elected Officials, the problem is not the Kings, but those who have benefited from the Kings and not contributed financially to the movement.

“African American citizens in this country and throughout the world should search their souls and consciences,” he said. “If we want to see the center controlled by the family, we should put the King Center back in our budgets.”

Many people in Atlanta, however, no longer seem to want the Kings to control the King Center.

From his modest office on Auburn Avenue, Howard said the Kings no longer spoke for his Sweet Auburn neighborhood, Atlanta or the nation.

“The Kings are a world away from us,” he said. “Down here, we have more communication with the National Park rangers who walk up and down the street.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.