Parole case may dog Huckabee

Pastor Jay D. Cole had two close friends. One was an inmate in the Arkansas state penitentiary. There, the minister would sit with Wayne DuMond “and pray and read the Bible.” For a while, the prisoner’s wife even lived in Cole’s home.

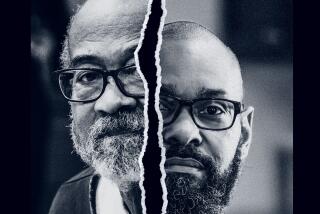

Cole’s friendship with Mike Huckabee ran deeper, back to when Huckabee was the youngest-ever head of the Arkansas Baptist State Convention. The two men produced Bible lessons on videotape. “We worked heavily with him when he got politically involved too,” Cole said.

A little over 10 years ago, the paths of these three men merged in Little Rock, the state capital, where Huckabee was the new governor. With Cole’s urging, and with DuMond insisting he was “born again,” Huckabee played a key role in setting free a rapist who was supposed to serve many more years, say three of the seven members of the state board that paroled DuMond.

After being released, DuMond moved to Missouri, where less than a year later he suffocated the mother of three in a Kansas City suburb. Police suspect that he killed another woman there as well.

How a convicted rapist went free has become an issue in today’s increasingly heated presidential campaign. As if out of nowhere, Huckabee has surged to a leading spot in public opinion polls in the Republican contest. Amid the new attention, he is facing questions about whether his deep Christian faith -- what on the stump he says “defines me” -- colored his view of Wayne DuMond’s case.

Trying to bury any doubts, Huckabee said this week that he had “considered” -- but then rejected -- the idea of using his powers as governor to commute DuMond’s sentence and release him for time served. The state parole board acted before he had to make a final call. It was the parole board, Huckabee said, that unlocked the cell door.

“It was a horrible situation, horrible. I feel awful about it in every way. I wish there was some way I could go back and reverse the clock and put him back in prison,” the candidate said at a news conference this week.

Though he acknowledged discussing the case with the state parole board, Huckabee said that conversation was “simply part of a broader discussion” initiated at the request of the board chairman. “I did not ask them to do anything,” he said.

Three board members recalled it differently. They said Huckabee raised the issue of DuMond’s release, asking to discuss the matter with them in a closed session. They said his religious beliefs, and the influence of the evangelical community from which he came, drove him.

“We felt pressured by him,” said board member Ermer Pondexter. “I felt compelled to do it. . . . It was a favor for the governor.”

Looking back, she added, “I regret it.”

Parole board member Deborah Springer Suttlar said Huckabee did not mince his feelings about DuMond: “He wanted him out.”

A committee of board members voted to parole DuMond. It took the action just before the deadline by which Huckabee would have had to decide what assistance, if any, he would grant to an inmate whom he had already said he wanted to help.

“He thought DuMond just grew up on the wrong side of the tracks, that he may have gotten a raw deal and a longer sentence than others under similar circumstances,” recalled board member Charles Chastain, who said he was the lone dissenter in a 4-1 committee vote to grant parole.

All seven members of the board had been appointed by Huckabee’s Democratic predecessors.

The board chairman declined to comment; one board member could not be reached and one said he did not remember details of the case. A seventh member is deceased.

Huckabee said at the news conference that he was unnerved by accounts from parole board and other critics that he played a larger role in DuMond’s release. “There will be people who will probably be brought forth to make statements but, you know, I can’t fix it,” he said. “I can only tell the truth and let the truth be my judge.”

Cole, the minister who befriended DuMond, said: “The governor felt compassion for Wayne. He was sorry for him. So, I asked the governor to help. I asked him if anything could be done. And Mike had a lot of people on his neck trying to get him to get Wayne released.”

“Many of them,” Cole added, “were in the Christian community.”

The story of the convict, the preacher and the governor who wants to be president rings with Gothic details -- rape and castration, a corrupt county sheriff and state politics. Finally, there is murder.

It opens in 1984, when a 17-year-old cheerleader, the daughter of a mortician called “Stevie” Stevens, was kidnapped from Forrest City by a man in a red pickup. The man drove her to a field and raped her. He used a knife to cut off her bra. The Forrest City case drew public attention, because the cheerleader was a distant cousin of then-Gov. Bill Clinton.

The police arrested DuMond, a skinny Vietnam War veteran, handyman and father of six. He had been suspected in a rape in Texas and as an accomplice to murder in Oklahoma. Those cases didn’t stick.

While DuMond remained free on bail awaiting trial, police were summoned to his home, where the bleeding suspect told them that several men had pushed their way in and castrated him. Some authorities were skeptical, theorizing that DuMond had castrated himself in a ploy for mercy -- to claim, once castrated, that he would no longer be a threat to women.

For a while, the local sheriff kept DuMond’s testicles in a fruit jar on his desk, with a sign: “This is what happens to men who go bad in my county.” DuMond sued the sheriff over that humiliation and won a $110,000 judgment. The sheriff went to prison in an unrelated extortion case and died there.

DuMond was sentenced to life in prison for rape, plus 20 years for the kidnapping. Clinton ignored his pleas for parole or a sentence reduction.

Once in prison, DuMond said he found religion.

“I became his spiritual director,” Cole said. “He was a nice fella, and it was hard to believe he could have done what he was accused of doing. And Wayne claimed to be saved. So, we’d sit and talk and pray for two hours, and other times he’d call me on the phone a lot. Collect. He was just wanting to know if I’d made any headway finding people who could help his situation.”

In 1992, Clinton was elected president, and the state’s lieutenant governor, Jim Guy Tucker, became governor. Tucker evaluated the DuMond case and found the life sentence, coupled with the castration, made for an unusually harsh punishment. He reduced the sentence to a fixed term of 39 years and six months; DuMond was now eligible for parole.

In 1996, Tucker was convicted of fraud in the Arkansas-based Whitewater investigation. Huckabee, the lieutenant governor, was elevated to governor.

Cole, meanwhile, was working to help DuMond. Cole said he talked to “probably a hundred people” about his hope of winning DuMond’s release, turning foremost to the evangelical community. He said many evangelicals were encouraged that DuMond had claimed a religious conversion, and that many joined Cole in writing to Huckabee about DuMond’s situation.

The clincher, he said, was their belief that DuMond had been “saved.”

“All of them thought Wayne was innocent,” said Cole. “And the governor knew about it. We talked about it together. But Mike was very careful. He was cautious about saying too much. In an elevated position like governor, you’ve got to be careful.”

Huckabee said the DuMond case was already “on my desk” when he became governor in July 1996. He announced that he was considering a commutation. Later, he acknowledged, he wrote a letter to the prisoner saying parole was a better option.

“Dear Wayne. . . . My desire is that you be released from prison,” the governor wrote. “I feel now that parole is the best way. . . .”

The rape victim, Ashley Stevens, became enraged. She and prosecutor Fletcher Long met with Huckabee at the Capitol. They warned him that DuMond would strike again.

At one point in the meeting, Stevens recalled, she stood up, put her face next to Huckabee’s and told the governor: “This is how close I was to DuMond. I’ll never forget his face, and you’ll never forget mine.”

The meeting ended, and Long, a Republican, could tell the governor was unmoved: “Most of what I think about him would be unprintable. His actions were just about as arrogant as you can get.”

The prosecutor added that Huckabee and Arkansas evangelicals were conned by DuMond’s contention that he had been “saved” -- a common ruse by prisoners.

“If you’re religiously converted,” Long said, “how do you go out and kill two women in Missouri?”

Before DuMond could be paroled, he had to find another state that would take him, a process that took several years. Texas did not want DuMond, nor did Florida. A new wife he had met while in prison was from Missouri.

So, in 1999, after serving 14 years of his sentence, DuMond relocated to the Kansas City area.

Less than a year later, Carol Shields was suffocated in a friend’s apartment. Scrapings of DNA under her fingernails led to DuMond. The day before DuMond was arrested in the slaying, another woman, Sara Andrasek, was killed in much the same way.

DuMond was convicted of killing Shields and in 2004 was sentenced to life in prison, this time without parole. He was not charged in the second slaying.

He died in 2005 in prison, of cancer of the vocal chords. He was 55.

Prosecutor Dan White of Clay County, Mo., the man who put him away for good, said: “The world’s a better place without Wayne DuMond in it.”

--

Times staff writer Richard Fausset contributed to this report.

--

GOP debate

The Republican presidential candidates will debate Sunday at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Fla. The 90-minute forum will be broadcast at 7 p.m. on Univision.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.