WORD OF MOUTH: ‘Lottery Ticket’ tries to beat the odds

Alcon Entertainment has been here before.

Seven years ago, the financier of “The Blind Side,” “The Book of Eli” and “Insomnia” took a shot at an urban comedy. “Love Don’t Cost a Thing,” an African American-themed remake of 1987’s high school romance “Can’t Buy Me Love,” was a middling success, grossing about $22 million in domestic release. But the movie business is not driven by middling successes, and Alcon hasn’t made another such movie until “Lottery Ticket,” which opens in wide release on Friday.

Alcon isn’t alone. Hollywood’s interest in comedies anchored by black casts is as fleeting as a soap bubble.

Over the years, studios and specialized film distributors have released any number of commercial hits led by African American performers, including 1995’s “Friday,” 1997’s “Soul Food,” 1999’s “The Best Man,” 2000’s “Big Momma’s House,” and 2002’s “Barbershop,” “Drumline,” 2005’s “Are We There Yet?” and this April’s “Death at a Funeral,” to cite but a few.

FOR THE RECORD:

‘Lottery Ticket’: An article in Thursday’s Calendar about the movie “Lottery Ticket” misspelled the name of Relativity Media’s Ryan Kavanaugh as Cavanaugh. —

These days, though, the genre nearly has become a one-studio monopoly: Lionsgate with its steady stream of popular Tyler Perry titles, with three films from the writer/director/producer/actor due next year: “We the Peeples,” “Madea’s Big Happy Family” and “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf.”

As Perry’s power has surged, some of the previous purveyors of movies aimed at black audiences have backed away.

New Line Cinema, the studio behind “Friday” and its sequels and once a reliable maker of urban comedies, is now focused on chick flicks ( “Sex and the City,” “Valentine’s Day,” “The Time Traveler’s Wife”) and mainstream sequels (including follow-ups to “Final Destination,” “Journey to the Center of the Earth” and “Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle”). After the unremarkable performance of its “Just Wright” and “Our Family Wedding,” Fox Searchlight earlier this summer pulled the plug on “Baggage Claim,” a romantic comedy that was to star “ The Curious Case of Benjamin Button’s” Oscar-nominated Taraji P. Henson.

“Lottery Ticket” nearly was ripped up in the retrenchment.

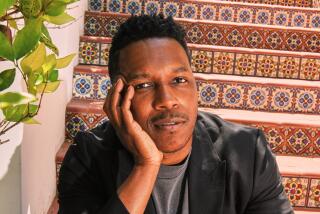

The story about a recent high school graduate who wins a massive jackpot but can’t immediately cash the ticket (thus creating more personal problems than any amount of money can solve) had been in development at Rogue Pictures, with rapper Chris Brown an early candidate to play the film’s lead role before his arrest in connection with an assault. When Ryan Cavanaugh’s Relativity Media bought Rogue from Universal Studios in early 2009, “Lottery Ticket” was orphaned. “It just didn’t fit into their plans,” says Abdul Williams, “Lottery Ticket’s” screenwriter. “We thought it was dead.”

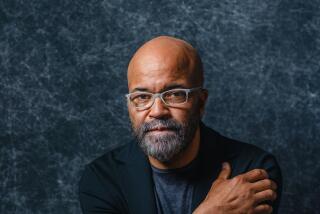

But Alcon, the production company launched by Federal Express founder and Chairman Frederick Smith, had just refinanced its production deal, and was obligated to lower its slate’s average budget, owing to the $82-million “Book of Eli.” “We were looking for a niche picture, and we didn’t really have one,” says Andrew Kosove, who runs Alcon with Broderick Johnson.

Alcon’s movies, which are released by Warner Bros., tend to have some positive social message — “The Blind Side” being a perfect example — and the company felt “Lottery Ticket” fit with its mission. “Even though the movie is very much of a popcorn movie, it has a moral center,” Kosove says. “And it’s really a lot about economic anxiety. Broderick and I thought it was an interesting story in these times.”

As written by Williams and directed by music video veteran Erik White (Fabolous, T.I.), the film’s Kevin Carson (now played by rapper Bow Wow) is an 18-year-old with entrepreneurial ambitions who wins a $370-million jackpot. Due to a holiday weekend, he has to sit on his ticket for several days, but everyone in the projects soon finds out about the coming windfall. Carson’s platonic relationship with a girlfriend (“Fame’s” Naturi Naughton), his friendship with his best friend (“Tropic Thunders” Brandon Jackson) and his interactions with a mysterious neighbor (“Friday’s” Ice Cube) are all transformed by his impending wealth.

Kosove describes Alcon’s experience on “Love Don’t Cost a Thing” as “a mixed one. We broke even on it, fortunately, but it did not do as well based on our expectations. And that really bugged me.” He says the company wanted to ensure that the $17-million “Lottery Ticket” appealed to a broader range of the black audience, not just the teens who attended “Love Don’t Cost a Thing.”

Consequently, “Lottery Ticket” is populated with older actors who may have unique constituencies. In addition to Cube, the film co-stars veterans Keith David (“Crash”), Terry Crews ( “The Expendables”), Loretta Devine (“Death at a Funeral”) and Gbenga Akinnagbe (“The Wire”). “The cool thing about a cast like this is they all bring a certain segment,” screenwriter Williams says.

Williams also knows that just as his film’s characters are playing the lottery, his movie is a Hollywood gamble.

“The reality now is that fewer movies of any kind get made,” Williams says. “And there’s no black ‘Avatar.’ There’s no black ‘Titanic.’ Not to pick on James Cameron, but when you do get a black movie made, there is more pressure on you.

“If ‘Lottery Ticket’ turns out to be a hit, all of a sudden the town will say that young urban comedies are hot again. Hopefully, people will say there’s an audience out there who still wants these kind of movies,” he says. “They don’t want to be preached to. They want to have fun.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.