Steve Jobs dies at 56; Apple’s co-founder transformed computers and culture

Steven P. Jobs, the charismatic technology pioneer who co-founded Apple Inc. and transformed one industry after another, from computers and smartphones to music and movies, has died. He was 56.

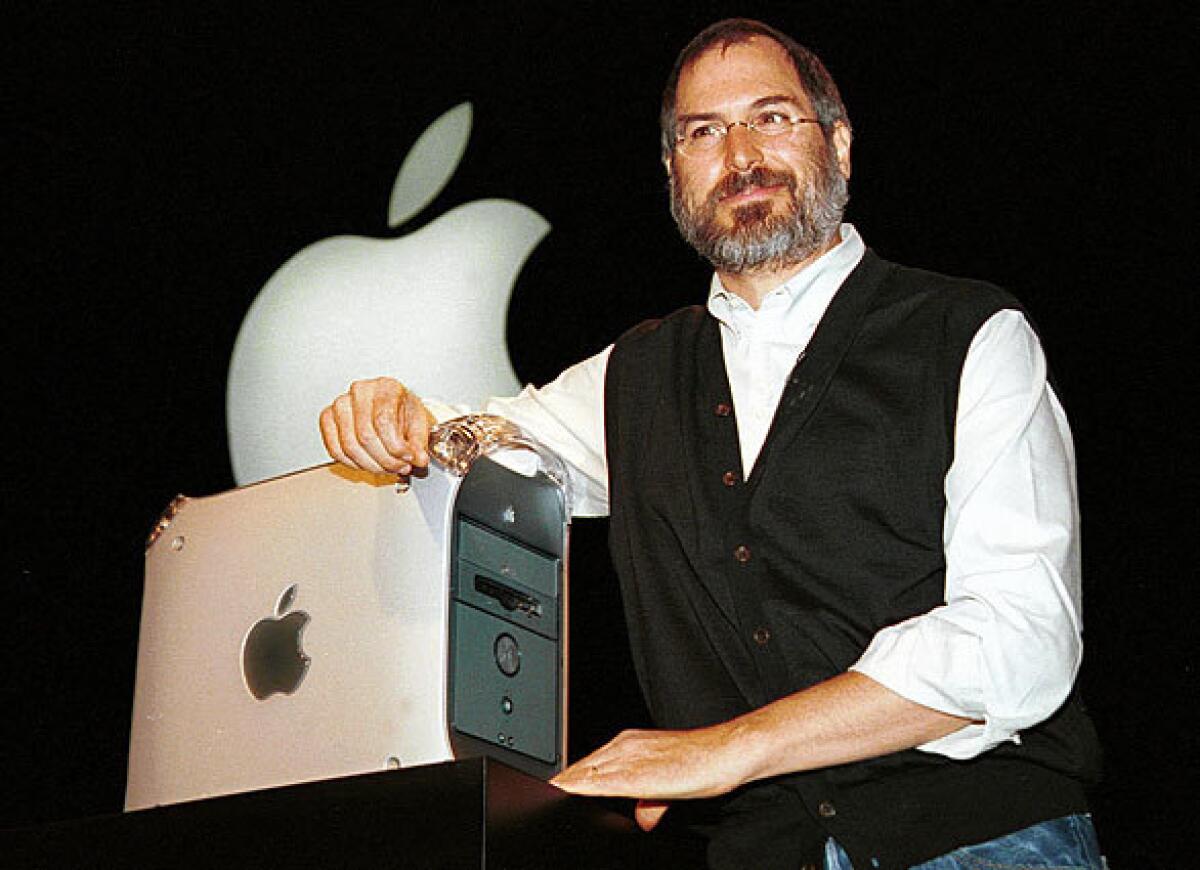

Apple announced the death of Jobs — whose legacy included the Apple II, Macintosh, iMac, iPod, iPhone and iPad.

“We are deeply saddened to announce that Steve Jobs passed away today,” Apple said. “Steve’s brilliance, passion and energy were the source of countless innovations that enrich and improve all of our lives. The world is immeasurably better because of Steve.”

He had resigned as chief executive of Apple in August, after struggling with illness for nearly a decade, including a bout with pancreatic cancer in 2003 and a liver transplant six years later.

Few public companies were as entwined with their leaders as Apple was with Jobs, who co-founded the computer maker in his parents’ Silicon Valley garage in 1976, and decades later — in a comeback as stunning as it seemed improbable — plucked it from near-bankruptcy and turned it into the world’s most valuable technology company.

Jobs spoke of his desire to make “a dent in the universe,” bringing a messianic intensity to his message that technology was a tool to improve human life and unleash creativity.

“His ability to always come around and figure out where that next bet should be has been phenomenal,” Microsoft Corp. co-founder Bill Gates, the high-tech mogul with whom Jobs was most closely compared, said in 2007.

In the annals of modern American entrepreneur-heroes, few careers traced a more mythic sweep. An adopted child in a working-class California home, Jobs dropped out of college and won the title “father of the computer revolution” by the age of 29. But by 30 he had been forced out of the company he had created, a bitter wound he nursed for years as his fortune shrank and he fought to regain his early eminence.

Once out of the wilderness of exile, however, he brought forth a series of innovations — unveiling them with matchless showmanship — that quickly became ubiquitous. He turned the release of a new gadget into a cultural event, with Apple acolytes lining up like pilgrims at Lourdes.

Jobs was born in San Francisco on Feb. 24, 1955, to Joanne Carole Schieble and Syrian immigrant Abdulfattah Jandali, unmarried University of Wisconsin graduate students who put him up for adoption. He was adopted by Paul Jobs, a high school dropout who sold used cars and worked as a machinist, and his wife, Clara.

Jobs’ willfulness and chutzpah were evident early on. At 11, he decided he didn’t like his rowdy and chaotic middle school in Mountain View, Calif., and refused to go back. His family moved to a nearby town so he could attend another school.

When he was 12 or 13, Jobs would recall, he called the home of William Hewlett, one of the founders of Hewlett-Packard Co., to ask about parts he needed for a device he was building. For Jobs, it led to a humble summer job on a Hewlett-Packard assembly line, which he compared to being “in heaven.”

While attending Homestead High School in Cupertino, Calif., Jobs met Steve Wozniak, who was nearly five years older. A technical wizard who was in and out of college, Wozniak liked to make machines to show off to other tinkerers.

The two collaborated on a series of pranks and built and sold “blue boxes” — devices that enabled users to hijack phone lines and make free — and illegal — calls.

In 1972, Jobs dropped out of Reed College in Oregon after six months but lingered on campus, sleeping on friends’ dorm-room floors. He sat in on classes that interested him, such as calligraphy, which later inspired him to offer Macintosh users multiple fonts, a feature that would become a fixture of personal computing.

He worked sporadically as an electronics technician at video game maker Atari Inc., traveled to India on a quest for enlightenment and found guidance from a Zen Buddhist master.

Meanwhile, Wozniak had created a computer circuit board he was showing off to a group of Silicon Valley computer hobbyists. Jobs saw the device’s potential for broad appeal and persuaded Wozniak to leave his engineering job so they could design computers themselves.

In April 1976, the two launched Apple Computer out of Jobs’ parents’ garage, reproducing Wozniak’s circuit board as their first product.

They called it the Apple I and set the price at $666.66 because Wozniak liked repeating digits. In the following year came the Apple II, which carried a then-novel keyboard and color monitor and became the first popular home computer. When the company went public in 1980, the 25-year-old Jobs made an estimated $217 million.

Whether pitching a product or wooing a job candidate, Jobs liked to paint what he was selling as part of a revolution, an idea that reverberates in Silicon Valley start-ups today.

“He was by far the most articulate person our industry has ever had,” said Esther Dyson, a longtime technology observer and entrepreneur.

When he approached PepsiCo executive John Sculley to become chief executive of Apple in 1983, Jobs asked him, “Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water or do you want to change the world?”

At Apple, Jobs spearheaded the creation of a computer he called Lisa (also the name of his daughter born to a former girlfriend). The cocky, headstrong Jobs tangled with Lisa engineers over the direction of the computer, and Apple executives curtailed his role in the project. “It hurt a lot,” Jobs told a Playboy interviewer.

Jobs turned his attention to a small research effort called Macintosh, producing what he described as “the most insanely great computer in the world,” with a graphics-rich interface and a mouse that allowed users to navigate much more easily than they could with keyboard commands.

In 1984, Apple promoted the Macintosh with a television spot that aired during the Super Bowl. The minute-long commercial portrayed a sledgehammer-hurling runner heroically smashing the image of a sinister Big Brother figure, who was preaching to an assembly of gray drones.

“On Jan. 24, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh,” the narrator announced. “And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’”

The Orwellian tyrant, as Jobs portrayed it, was rival IBM Corp., then the dominant computer maker. In a 1985 Playboy interview, he cast IBM as the great enemy of innovation and described the battle as nothing less than light versus dark in the race for the future.

“If, for some reason, we make some giant mistakes and IBM wins, my personal feeling is that we are going to enter sort of a computer Dark Ages for about 20 years,” he said. “Once IBM gains control of a market sector, they almost always stop innovation. They prevent innovation from happening.”

Macintosh inaugurated an era of visual, clickable computing that remains the norm today, and its look, adopted by Microsoft for its Windows software, became a global standard. Still, although Jobs was a celebrity and wealthy beyond imagining, the Macintosh struggled early to capture sales and trailed the increasingly popular IBM PC.

As panic set in about the Macintosh’s problems, tensions flared between Jobs and Sculley, who, with the Apple board’s blessing, further reduced Jobs’ role. Jobs resigned in 1985, a 30-year-old tech king deposed from the palace he had built. As he saw it, he was fired.

“What had been the focus of my entire adult life was gone, and it was devastating,” Jobs later recalled in a Stanford University address. “I didn’t really know what to do for a few months. I felt that I had let the previous generation of entrepreneurs down.

“I was a very public failure.”

He started NeXT Computing, which made computers for higher education and corporations. Technologists took to the computers — including British computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee, who used them to create the World Wide Web in the early 1990s. But at $6,000, they were too expensive for consumers and failed to catch on.

In what many saw as a hobby, Jobs began dabbling in moviemaking technology in 1986, buying a small computer graphics division from filmmaker George Lucas’ Lucasfilm Ltd. and renaming the company Pixar.

Around that time he met Laurene Powell, a Stanford business student, and they were married in 1991 by a Buddhist monk.

Jobs also found his biological mother, Joanne Simpson, and biological sister, Mona Simpson. He and his sister became close, and she dedicated her 1992 novel “Anywhere But Here” to him and their mother.

By then, he had established a relationship with his daughter Lisa. Jobs initially denied paternity and refused to pay child support. He eventually accepted her as his child, and she is now a New York writer.

NeXT and Pixar struggled financially, and he sank much of his personal fortune — upward of $70 million — into the two companies, according to Alan Deutschman’s “The Second Coming of Steve Jobs” (2000). Setbacks mounted as he slashed staff and scaled back both operations.

A 1993 Wall Street Journal article described “the decline of Mr. Jobs,” saying that his vision for NeXT resembled “a pipe dream” and portraying him as a once-great but increasingly irrelevant figure who might survive “as a niche player.”

The turnaround began in late 1995 when Pixar released “Toy Story,” the first feature-length computer-animated film, and it became a smash hit. Pixar went public one week later, making Jobs a billionaire, and has continued to produce box-office hits such as “Up,” “Finding Nemo” and two “Toy Story” sequels. Walt Disney Co. bought Pixar for $7.5 billion in 2006, making Jobs the entertainment giant’s largest shareholder.

In Jobs’ absence, Apple had been foundering as its share of the computer market shriveled. Seeking new software for the Macintosh, Apple decided on NeXT’s system, and bought the company for $377 million.

Jobs came back to Apple as a “special advisor” in 1996, but within a year he orchestrated the ouster of most of Apple’s board and had himself installed as chief executive. He reshaped a moribund company into a $380-billion technology titan, which this year temporarily surpassed Exxon Mobil Corp. as the world’s most valuable company.

The comeback was powered by a string of blockbuster products for which Jobs is largely credited — each of which had far-reaching effects in both culture and industry.

“To have your whole music library with you at all times is a quantum leap in listening to music,” he said in a 2001 presentation. “How do we possibly do this?” A moment later, he pulled the first iPod from his jeans pocket to show off the answer.

With the iPod’s release, Jobs lighted the way for the entertainment industry in the digital age. The iPod became Apple’s most popular product and soon captured about 70% of the market for digital music players.

Two years later, through deals that Jobs brokered with the recording industry, Apple opened its iTunes online store, which is now the country’s No. 1 music retailer.

With iTunes — which expanded to selling movies, TV shows, books and games — Jobs transformed Apple from a computer maker into one of the primary gatekeepers for the explosion of online media.

The iPhone, introduced in 2007, gave the cellphone a touch screen and a Web browser and enabled the growth of a booming industry of small mobile games and applications. It was then that Jobs dropped the word “Computer” from Apple’s name to make it simply Apple Inc.

Last year, Apple released its iPad tablet computer, a wireless reading, gaming and Web-surfing slate that has sold nearly 30 million units since its release.

In a testament to Jobs’ knack for picking transforming technologies, many industry analysts believe the iPad will hasten the demise of the laptop and desktop computers that Jobs himself once helped bring to prominence.

In his second term at Apple, Jobs’ instincts became the company’s internal compass. Unlike many chief executives, Jobs shunned focus groups and consumer surveys, personally driving Apple’s search for the next great idea.

“A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them,” Jobs once told BusinessWeek magazine.

He had a cult-like following, and he mesmerized audiences when unveiling Apple’s newest products, but no one was shown anything until Jobs said it was time. He kept a tight lid on information flowing out of the Cupertino company.

He was known as an imperious boss with little patience for weakness, one who launched blistering tirades that left subordinates fuming, or in tears.

“Steve tests you, challenges you, frightens you,” Todd Rulon-Miller, a friend and NeXT executive, said in “The Second Coming of Steve Jobs.” “He uses this as a tactic to get to the truth.”

Mercurial and brilliant, Jobs presented himself as an outsider even at the apex of American business, a convention-bucking visionary who was willing to wade into new industries to do battle with movie studios, record labels and cellphone giants. As a Buddhist and vegetarian following the principles of minimalism, he nearly always appeared in public in a black turtleneck, worn jeans and sneakers.

Apple’s “Think Different” ad campaign, with its parade of iconic pioneers and world-shaping figures from Einstein to Gandhi, relentlessly promoted the concept of triumphant individual genius. The implicit hero was Jobs himself, who embodied that ideal as much as any modern American.

Jobs was not afraid to blast rivals — chief among them software giant Microsoft, whose products he once described as “really third-rate” and aesthetically tasteless. The skewering later became more playful, with TV commercials portraying Microsoft users as frumpy and bookish and hipper Mac fans as stylish and quick-witted.

An intensely private person, Jobs rarely discussed his personal life and had little taste for the trappings of celebrity. As a philanthropist, his public profile paled beside that of Gates and Warren Buffett, and critics wondered why Jobs — who had an estimated net worth of $8.3 billion — didn’t give more money away, or if he did, why he kept it secret.

For years, Jobs’ health was an issue that wouldn’t go away. Although he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2003, he did not reveal his illness for nine months, according to a Fortune magazine report. He finally agreed to surgery in 2004.

After the surgery, Jobs announced that he had recovered. But in 2009, he underwent a liver transplant that was only later brought to light by the Wall Street Journal. As time went on, Jobs looked noticeably thinner in public appearances.

In a Stanford commencement speech in 2005, Jobs spoke at length about mortality and its value as a force against complacency.

“Death is very likely the best invention of life,” he said in the speech. “All pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure, these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important.”

Jobs’ survivors include his wife, their son Reed Paul and their daughters Erin Sienna and Eve, as well as his daughter Lisa Brennan-Jobs.

Timeline: The life and work of Steve Jobs

christopher.goffard@latimes.com

Former Los Angeles Times staff writer Michelle Quinn contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.