Column: Eli Lilly assails Indiana antiabortion law — after plying its supporters with campaign funds

Last month, I wrote that the surge in antiabortion laws in red states might induce working professionals to refuse job offers in those states or even produce a flood of exits.

The evidence then was largely anecdotal. Now, thanks to the giant pharmaceutical firm Eli Lilly & Co., there’s hard evidence that we stand on the water’s edge.

This law will hinder Lilly’s — and Indiana’s — ability to attract diverse scientific, engineering and business talent from around the world.

— Eli Lilly & Co. protests Indiana antiabortion law

Lilly, one of the largest employers in Indiana, said late last week that the recent enactment of one of the nation’s strictest antiabortion laws would force it to “plan for more employment growth outside our home state.”

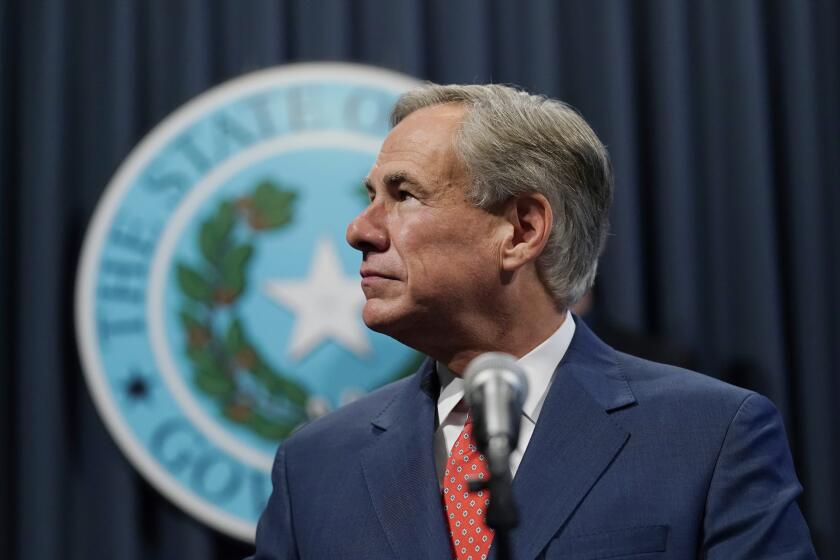

Lilly said it is concerned that the measure, which passed at a special session called by Republican Gov. Eric Holcomb, “will hinder Lilly’s — and Indiana’s — ability to attract diverse scientific, engineering and business talent from around the world.”

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The company’s statement noted that although Lilly has “expanded our employee health plan coverage to include travel for reproductive services unavailable locally, that may not be enough for some current and potential employees.”

A multinational company that has been based in Indianapolis for 145 years, Lilly also took a swipe at the legislators who passed the law and at Holcomb, who signed it on Aug. 5.

Although abortion is “a divisive and deeply personal issue with no clear consensus among the citizens of Indiana,” the company said, the state “opted to quickly adopt one of the most restrictive anti-abortion laws in the United States.”

These are strong words from a major employer. They’re undermined, however, by Lilly’s financial support for many of the state legislators who voted for the measure — including its two Republican sponsors, Sen. Jean Leising and Rep. Wendy McNamara. Lilly also contributed to Holcomb’s 2016 gubernatorial campaign and 2020 reelection campaign.

That points to the inescapable drawbacks of allowing corporations to contribute to political campaigns, for democratic values as well as the social principles espoused by the companies themselves. Corporations normally make political contributions to advance their own narrow interests, which often are in conflict with the interests of ordinary citizens.

The very idea that a multibillion-dollar corporation (Lilly reported $5.6 billion in profit on $28.3 billion in revenue last year) should be able to pay thousands of dollars to elected representatives to get its way undermines the political process.

Lilly’s reaction to the antiabortion law is reminiscent of the firestorm ignited by another right-wing law enacted by Indiana political leaders. This was the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, passed in 2015 and signed in a secret ceremony by then-Gov. Mike Pence.

Antiabortion and other conservative policies are driving students and high-paid professionals away from red states.

That law was widely seen as an attack on LGBTQ rights. After businesses threatened to leave the state or curtail their activities there, including the NCAA, which spoke pointedly about the law’s impact on its national basketball championship in Indianapolis, the law was modified to allow local governments to maintain or enact their own antidiscrimination policies.

Lilly was among the big Indiana companies that urged the Legislature to “fix” the law to make it less draconian. Lilly contributed a total of $46,000 to Pence’s successful 2012 gubernatorial campaign and his 2016 reelection campaign, which ended when he was chosen as Donald Trump’s running mate that year.

Before we delve into the implications of Lilly’s latest statement — and into the company’s own support for many of the legislators who voted for the law — here are some points about the law itself and the antiabortion landscape.

As is well known by now, the Supreme Court’s June 24 decision in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturned the guaranteed right to abortion that the court established through its decision in Roe vs. Wade 49 years ago.

Laws to ban abortion in the ruling’s wake are planned or pending in 26 states. Of those states, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which supports women’s reproductive health rights, 13 have “trigger” laws, which either went into effect immediately after the court ruled, or will do so after a brief delay or a routine official certification.

Signs have been mounting that professionals may be averse to moving to states with strict abortion bans. Among the professions likely to be most deeply affected is medicine, especially in the obstetrics and gynecology fields. Healthcare staffing firms say that candidates in those fields are rejecting offers to move to red states by the score, according to a survey by the Washington Post.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was America’s most detested law. Why are some anti-abortion states trying to duplicate it?

Indiana is the first state to actually enact a new antiabortion law since the court’s ruling. Its enactment came only three days after voters in Kansas overwhelmingly supported abortion rights by rejecting a constitutional amendment that would have opened the way for antiabortion legislation in that state.

The Indiana law, which will go into effect Sept. 15, bans almost all abortions. There are narrow exceptions for rape and incest, in which case the victim has 10 weeks to get an abortion. Abortions are also permitted when the long-term health and life of the mother are at risk and for abnormalities that render the fetus nonviable.

Abortion clinics unaffiliated with hospitals are outlawed, eliminating the locations where 98% of abortions in Indiana took place, according to the Indianapolis Star. The newspaper also reported that only six hospitals in Indiana performed abortions last year, only one of which is located outside Indianapolis.

The law subjects doctors who perform illegal abortions to criminal sanctions, including up to six years in jail.

Legislators crowed about their achievement in passing the law. “This is a monumental day for the unborn in Indiana, Leising said.

Leising added that the law “put Indiana in a position to be a shining example of how to move past abortion and give mothers and families the ability to raise happy, healthy children.”

Gov. Holcomb boasted that passage of the law fulfilled a commitment he made after the Dobbs ruling “to support legislation that made progress in protecting life.”

It’s proper that Eli Lilly, which depends on a professional workforce to pursue its business, would be concerned enough about this law to speak out. The company employs more than 10,000 workers in Indianapolis, among its 15,400 workers in the U.S. and about 35,000 worldwide.

But here’s the dark side of its hand-wringing: Lilly has supported many of the legislators who voted in favor of this law with campaign contributions for years.

California’s role as a beacon of women’s healthcare rights is about to become stronger.

Even if Lilly had not donated a dime to state legislators, it’s probable that the antiabortion measure would have passed — the vote in favor was 62 to 38 in the House of Representatives and 26 to 20 in the state Senate.

Lilly contributed a total of $79,550 to 15 of the representatives who voted for the bill, and $53,900 to 12 of the senators. That’s according to a state database that tracks campaign contributions at least as far back as 2008.

But it’s conceivable that the company would have had more sway over Holcomb, whose signature was the crucial step in the measure’s enactment. Lilly gave Holcomb’s campaign committee about $66,000 starting in 2016, when Holcomb first ran to succeed Pence as governor.

Lilly declined to comment on its support of the politicians who passed a law the company thinks is so inimical to its own interests and those of Hoosiers generally. Nor would the company comment on whether it had tried to head off the law prior to its enactment.

The firm certainly never made a public statement prior to the legislative vote. Indeed, its name was absent from an open letter circulated by the ACLU of Indiana prior to the vote and signed by nearly 300 Indiana employers.

“Restricting access to comprehensive reproductive care, including abortion, threatens the health, independence and economic stability of our employees and customers,” the letter warned. “It impairs our ability to build diverse and inclusive workforce pipelines, recruit top talent across the states, and protect the well-being of all the people who keep our businesses thriving day in and out.”

Also missing from the letter was Cummins Inc., a manufacturer of heavy machinery based in southern Indiana. Cummins, however, issued its own statement voicing its discontent with the law.

“We are deeply concerned about how this law impacts our people and impedes our ability to attract and retain a diverse workforce in Indiana — concerns that we have voiced to legislators,” the company said.

“Cummins believes that women should have the right to make reproductive healthcare decisions as a matter of gender equity, ensuring that women have the same opportunity as others to participate fully in the workforce and that our workforce is diverse. This law is contrary to this goal and we oppose it.”

The company noted that “this law does not affect our right to offer reproductive health benefits and we will continue to offer such benefits to our employees.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.