Column: Is America cheating its children to subsidize old people? Refuting a common falsehood

Whether it’s because the current partisan environment has us fixated on age in America, or because everyone is seeking an explanation for Americans’ discontent with a growing economy, or for some other reason, an old yarn about a generational war in the country has been making the rounds lately.

Over just the last four weeks, the idea that America is subsidizing its seniors at the expense of future generations has surfaced in the Washington Post (“Why we’re borrowing to fund the elderly while neglecting everyone else”), the Wall Street Journal (“Older Americans Are Better off Than Ever”) and twice in the New York Times (“For the Good of the Country, Older Americans Should Work More and Take Less,” and “Older Americans are Winning the Battle of the Generations”).

It also played a starring role in an exceptionally dumb article about Social Security at Slate.com that I deconstructed just last week. But since it appears in many contexts other than Social Security, and seems fated to become a common meme in the coming presidential election, I think it’s worth a focused examination all its own.

Social Security is not a big subsidy to retirees.

— Economist Dean Baker debunks a common and incorrect claim

Some of the recent articles have been accompanied by illustrations of happy, active seniors at play, presumably at the expense of their children or grandchildren or society at large.

(The New York Times’ illustrations were somewhat more sinister, consisting of artworks depicting lazy, wizened old men allowing themselves heedlessly and heartlessly to be physically carried about by younger people, including children, doubled over from the weight.)

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

These pieces would be instructive for policymakers, if they were true. But they’re not true.

Rather, they’re all variations on an old meme known as “the undeserving poor,” which has been commonly deployed to imply that the recipients of government assistance are layabouts and malingerers sucking up resources from hardworking taxpayers. In this case, the targets can be defined as “the undeserving old.”

The worst enemies of Social Security are would-be journalists who don’t do their homework before writing about it, and consequently get everything wrong.

What the most recent screeds tend to have in common is the notion that we spend enormously greater sums on elderly people than on our children, and that it’s an economic choice with inescapable consequences in a fiscal zero-sum game — “the fundamental challenge that clouds our long-term fiscal outlook,” writes Catherine Rampell, the author of the Washington Post’s version.

The subtext is that by monopolizing America’s resources, the powerful seniors’ lobby is depriving our children of sustenance and adequate healthcare. Spending on Social Security and Medicare is the main culprit: The cost of entitlements, Rampell writes, “will continue to crowd out future spending obligations in years ahead as the country ages and birthrates fall.”

But that’s completely wrong. What Rampell depicts as a fiscal inevitability is nothing of the kind. The notion that spending on seniors cuts directly into our capacity to spend on children reflects a political choice. It’s a moral test, not an economic one, and one that we consistently fail.

The truth is that America has more than enough resources to meet all its social needs, of all generations. If it has not done so, the reason isn’t that resources are scarce, but that those who wield power in government have chosen to veto spending that benefits children and young people (who, of course, don’t vote).

Let’s examine how this worked recently, using the Child Tax Credit as our laboratory sample.

The credit, which was originally enacted in 1997, was enhanced in 2021 as part of the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan, a pandemic recovery measure. The American Rescue Plan increased the credit to an annual $3,000 per child ($3,600 for children under age 6), from $2,000. It raised the maximum age of children eligible for the credit to 17 from 16.

The American Rescue Plan also made the credit fully refundable, meaning that it went to families regardless of whether or how much they paid in federal income taxes. The preexisting program’s work incentives, which reduced the credit for lower-income families, were rescinded.

The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimated the annual cost of the enhanced child credit at about $12 billion a year.

Is this an expenditure that the cost of Social Security and Medicare rendered unaffordable? Certainly not in comparison with other things that landed on the federal government’s expense ledger, such as the tax cuts enacted by Republicans for the benefit of corporations and wealthy people.

America’s retirement system is already among the worst in the developed world. If new House Speaker Mike Johnson were to get his way, it would be far worse.

Their cost has been estimated by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a billionaire-funded Washington think tank staffed by deficit hawks, at $1.5 trillion over 10 years, or $150 billion a year. If you’re looking for expenditures that crowd out spending on children, you could start and finish right there.

(You can be sure that the commission being launched by House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) to examine the cost of “entitlement” programs will ignore those figures.)

The Child Tax Credit enhancements reduced the child poverty rate in America by almost one-third, to 12.1% by the end of 2021. That worked out to lifting 3.7 million children out of poverty. When Congress failed to extend the enhancements beyond the end of 2021, the child poverty rate jumped up to 17%. (Black and Latino families were hit even harder.)

In other words, the Child Tax Credit had worked exactly as expected. It did so, moreover, without having any measurable effect on inflation.

Yet its purported inflationary impact was among the rationales offered by the credit’s enemy-in-chief, Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.), for killing the enhancements. Manchin had other objections, as it happened, but they were all equally specious. They included the absence of work requirements, which as I’ve shown time and again accomplish nothing in terms of raising employment but do make all such programs more expensive to run.

Rampell, drawing on statistics developed by C. Eugene Steuerle — who happens to be a co-author of one of the New York Times pieces — wrote in the Washington Post of America’s “seemingly bottomless commitment to add debt on behalf of retirees.” (Social Security, by the way, doesn’t add debt to the federal budget — in fact, it lends money to the government, taking interest-bearing Treasury securities in return.)

Rampell selects as an example a single man who earned the average wage every year of his adult life before retiring in 2020 at age 65, paying about $470,000 in Social Security and Medicare taxes and receiving benefits projected to total $640,000 in retirement — one of the system’s “lucky individuals,” she writes.

According to Steuerle’s figures, however, the “lucky individuals” receiving this subsidy are mostly people at the lower end of the income scale. The projected benefits of those with average lifetime earnings of less than about $66,000 a year in 2023 dollars do exceed the payroll taxes they paid over their lifetimes, though not by much. The single male with average annual lifetime earnings of $66,000 who retired in 2020, for instance, will have paid an estimated $367,000 in Social Security taxes but will receive a projected $383,000 in benefits.

Those with higher lifetime earnings will have paid for their own benefits through payroll taxes, Steuerle shows, and the higher their income, the more they’ve paid. Those with maximum taxable earnings ($160,200 in 2023 dollars) will have paid about 40% more in taxes than they receive in benefits. (Some of the excess will go to cover the little-understood insurance features of Social Security — its disability and dependent coverages.)

The GOP’s far-right wing want to use a shutdown threat to take aim at school funding, children’s healthcare and food, housing and heating assistance. What’s to like?

In other words, as economist Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research observes, these figures demonstrate that, contrary to the generational war hype, by Steuerle’s calculations young people are not really paying for the benefits of their elders. “Social Security is not a big subsidy to retirees,” he says. The working poor receive a subsidy, but would anyone really call them “lucky”? The truly fortunate in our society are paying for their own Social Security benefits.

It’s true that retirees typically receive more in Medicare benefits than they have paid for through the payroll tax. But that’s the direct result of America’s failure to get a grip on per capita healthcare costs, which run (unnecessarily) at more than twice the average of all developed countries. That’s a political choice, too — the choice by lawmakers unwilling to get off their duffs to bring those costs under control, say, by capping prescription drug prices.

All this should provide some context to the constant drumbeat from budget conservatives that we’ll need to cut benefits to keep Social Security afloat. As Baker points out, cutting the Social Security “subsidy” would mean reducing benefits for those with average lifetime earnings below $66,000. No one in that category is living what most people would consider a carefree life.

They’re certainly not in the category of retirees who, as Steuerle described them in his New York Times op-ed, “live independently, play golf or pickleball daily and travel far and wide.”

That brings us to another point about one of the most commonly mentioned “solutions” to the consequences of the supposed generational war: raising the retirement age.

Former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, currently running for second place in the GOP presidential nomination sweepstakes, emitted a fire hose of misconceptions and lies in an appearance on Bloomberg News in August, starting with the assertion that Social Security and Medicare are heading for bankruptcy, which is completely untrue.

She went on to suggest that “we change retirement age to reflect life expectancy....What we do know is 65 is way too low.”

Actually, the Social Security full retirement age is not 65. For those reaching age 64 this year, it’s 66 and 10 months, and for those 63 and younger, it’s 67 — dates that were set in 1983, which should have given Haley enough time to get up to speed. Anyone can start collecting at age 62, but only by taking a haircut of nearly 30% in annual benefits.

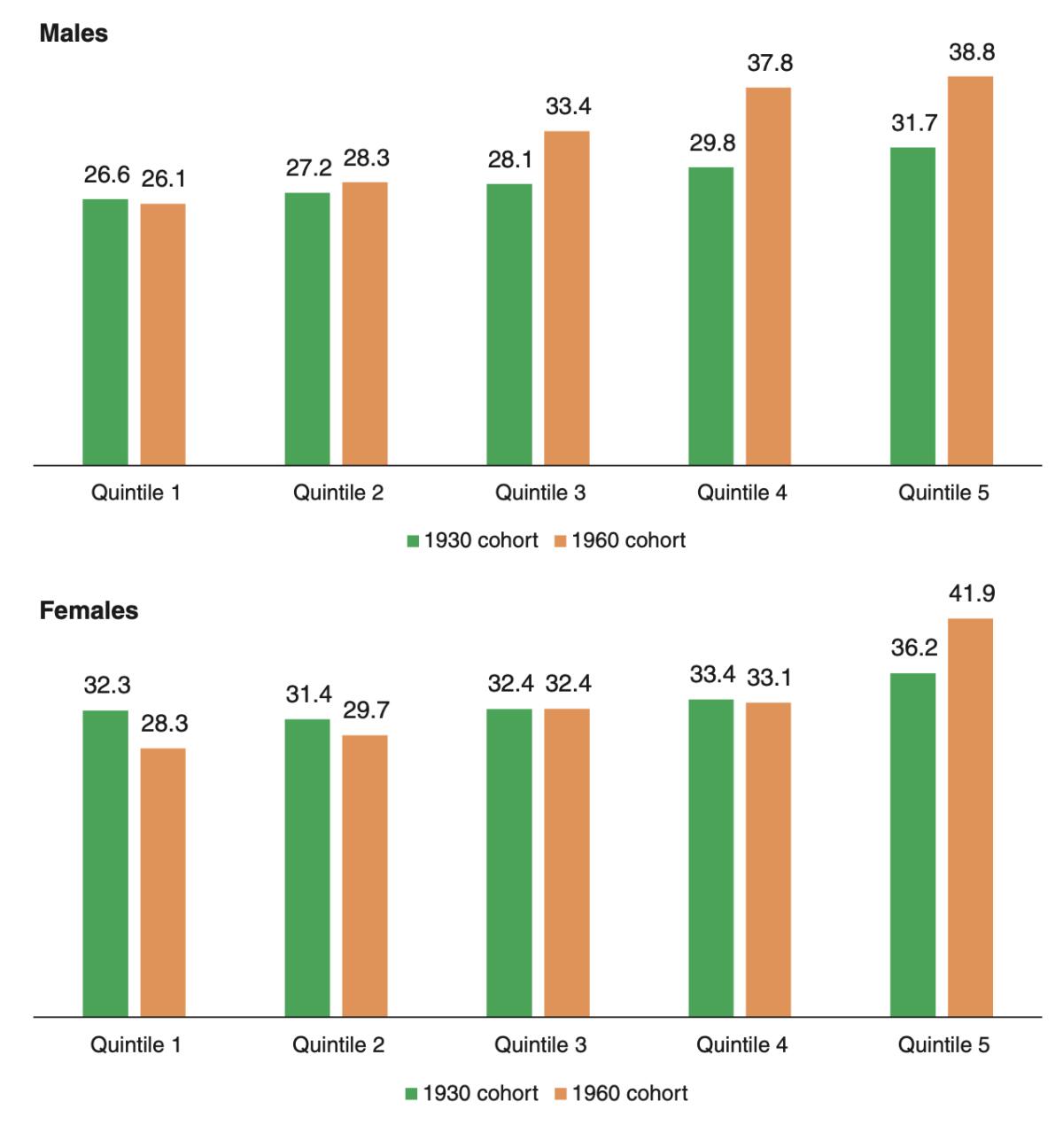

Life expectancy is a moving target, varying by race, educational attainment and income. Indeed, new figures from the National Academy of Sciences show a dramatic effect from the last of those metrics. Among people born in 1960, those in the lowest 20% of income earners — households earning $28,000 or less — males reaching age 50 could expect on average to live to age 76 and females to age 78.

Among those in the highest 20% of earners — households with about $150,000 in average earnings — life expectancy for those reaching age 50 is nearly 89 for males and 92 for females. The gap has widened considerably over the last 30 years, the National Academy of Sciences found.

Does Haley know of a way to make increases in the retirement age more equitable, given these circumstances? One would doubt it, since she also told Bloomberg that “instead of cost-of-living increases, we do it based on inflation.” Um, Ms. Haley, cost-of-living increases are based on inflation.

The bottom line is that all this talk of generational war is a diversion, aimed at obscuring what really accounts for inequality in our economic system. It’s not the young versus the old, but the rich versus all the rest, a battle in which the 1%, determined to hold on to all that they have, convince the 99% by distracting them with talk of “generational war.”

As long as politicians and the press buy this act and sell it to the public, the rich will be winning.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.