Gilroy shooter meticulously planned attack, was armed for battle

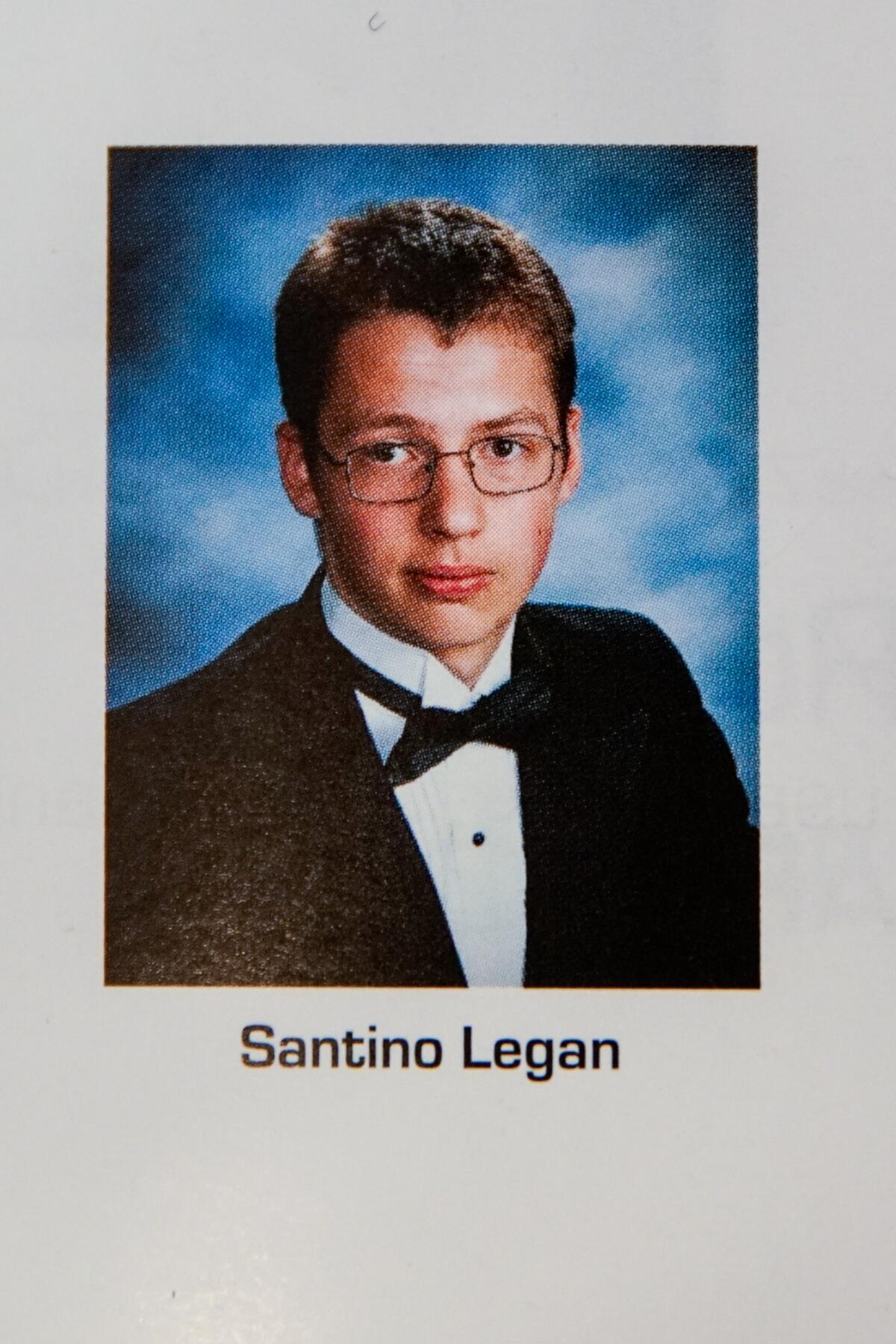

WALKER LAKE, Nev. — In the hours before the Gilroy Garlic Festival attack, Santino William Legan went shopping alone at several big-box stores in the area. It’s unclear what he bought, but sometime in the afternoon, authorities say, he drove to the festival to carry out a rampage.

He parked on the northeast side of the festival grounds, carrying a bag of ammunition and an AK-47-style rifle he’d recently purchased in Nevada. He left a shotgun behind in the car and made his way up a heavily wooded creek — ditching the bag on the way — and eventually cut through a fence to get inside.

Investigators said they had retraced Legan’s final day with video footage and a thorough search of the creek area. But they are still struggling to understand what motivated the 19-year-old Gilroy native to open fire Sunday, killing three young people and leaving a dozen more injured at the famed food festival. Authorities say they believe their best chance is through the gunman’s digital footprint.

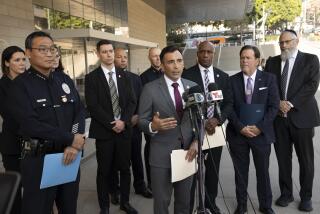

“A review of digital media historically has been very revealing in terms of somebody’s mindset, ideological beliefs, intentions,” Craig Fair, assistant special agent in charge of the FBI’s San Francisco office, told reporters at a news conference Tuesday afternoon.

In the last two days, investigators have collected hard drives and thumb drives from Legan’s home in Nevada, where he recently lived and purchased the rifle used in the attack, and searched his home in Gilroy.

A law enforcement source said Tuesday that authorities had recovered extremist materials during a search, though the source would not elaborate on their nature.

Authorities have scoured social media sites and are trying to get into Legan’s phone to figure out whom he was in touch with and what sentiments he was sharing with others.

“Everyone wants to know the answer: Why?” Gilroy Police Chief Scot Smithee said.

Getting answers has been frustratingly slow. Few people in Legan’s life have come forward to talk publicly about him in Gilroy and Nevada. And his public face on social media sites has been limited to a few posts. They suggest a racial animus, but detectives on Tuesday said there was no indication that he targeted victims based on race or class.

All our stories of Gilroy Garlic Festival shooting in one place

In the San Bernardino terror attacks that killed 14 and wounded 22, the digital footprint of the shooters yielded a considerable history of aspiring to commit a holy war on America. The killers in that case were so aware of it that they tossed away their laptop’s hard drive.

But in the 2017 mass shooting in Las Vegas, authorities were unable to ascribe a motive for Stephen Paddock’s rampage, which claimed 58 lives during the Route 91 Harvest country music festival, despite a year of investigation.

“Unfortunately that’s not uncommon to have a situation like this and never really truly understand what the motive was,” said Peter Simi, a Chapman University professor who studies political extremism and violence. It is misguided, Simi said, to try to identify a single motive.

“Often what happens is … multiple factors are driving them toward the violence they commit. A series of things are motivating them — some personal, some political, some religious.”

Before the attack, Legan posted a photo on Instagram of a Smokey Bear sign warning about fire danger, with a caption instructing people to read an obscure novel glorified by white supremacists: “Might Is Right” published under the pseudonym Ragnar Redbeard.

The book, published in 1890, includes discredited principles related to social Darwinism that have been used to justify racism, slavery and colonialism, said Brian Levin, director of Cal State San Bernardino’s Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism.

“The killer intended to send a message,” Levin said. “It would seem his postings would be probative of his motive, but what it doesn’t tell us is whether there is some mental instability, some stressor, some accomplice or peer group. Oftentimes, these kinds of killers act on idiosyncratic motives as well.”

Legan grew up in Gilroy and relocated to Walker Lake, Nev., sometime in the spring, authorities said.

He kept a low profile — the Mineral County district attorney’s office said Legan had no run-ins with the law, and sheriff’s officials said they’d had no previous contact with him.

Gilroy, California Garlic Festival Shooting: Here are cities hit by mass shootings around the country.

He was seldom seen and barely heard but was certainly noticed by Walker Lake residents. Mineral County Sheriff Randy Adams said people didn’t fade into a small town easily, especially when they’re new. “You’d stand out,” he said.

But Legan didn’t make much of an impression during his short time in this rural county of about 4,500.

Spud Winn, who lives in a row of apartments across from where Legan resided, said he saw him walk to the mailbox and saw him occasionally leave the gray triplex.

“I never even heard his voice,” Winn said.

The bearded 60-year-old construction worker said most people kept to themselves around the lake, which has been sucked dry by drought and farms upstream from its main water source, the Walker River.

Its glory days of being a resort town with crowds coming to fish its waters for trout have been gone for years — though there is a robust campaign to save Walker Lake through websites and court cases. Now it’s largely quiet.

But why a teenager would come to Walker Lake remained mysterious to residents and local officials.

Winn said an older woman used to live in the unit raided by police Monday morning after the shooting in Gilroy. He figured it was a relative.

Another neighbor who asked not to be identified said she once rented the same unit Legan had inhabited and said the older woman hadn’t been seen for months. Mineral County Dist. Atty. Sean Rowe said the community was made up mostly of fixed-income retirees.

Rowe said authorities searched a triplex unit where Legan lived. Court documents showed they retrieved weapon-related items, including a bulletproof vest, empty weapon and ammunition boxes, a pocketknife, a gun light, a camouflage backpack, pamphlets on guns, a sack of ammo casings, a gas mask and gloves.

They also took electronics: three hard drives, three thumb drives, a flip phone and a computer tower. They found a letter to him from a woman, according to the court records.

Neither Rowe nor Adams was aware of Legan doing any shooting in the area.

“There isn’t a public range around here, but there is a lot of public land,” Rowe said.

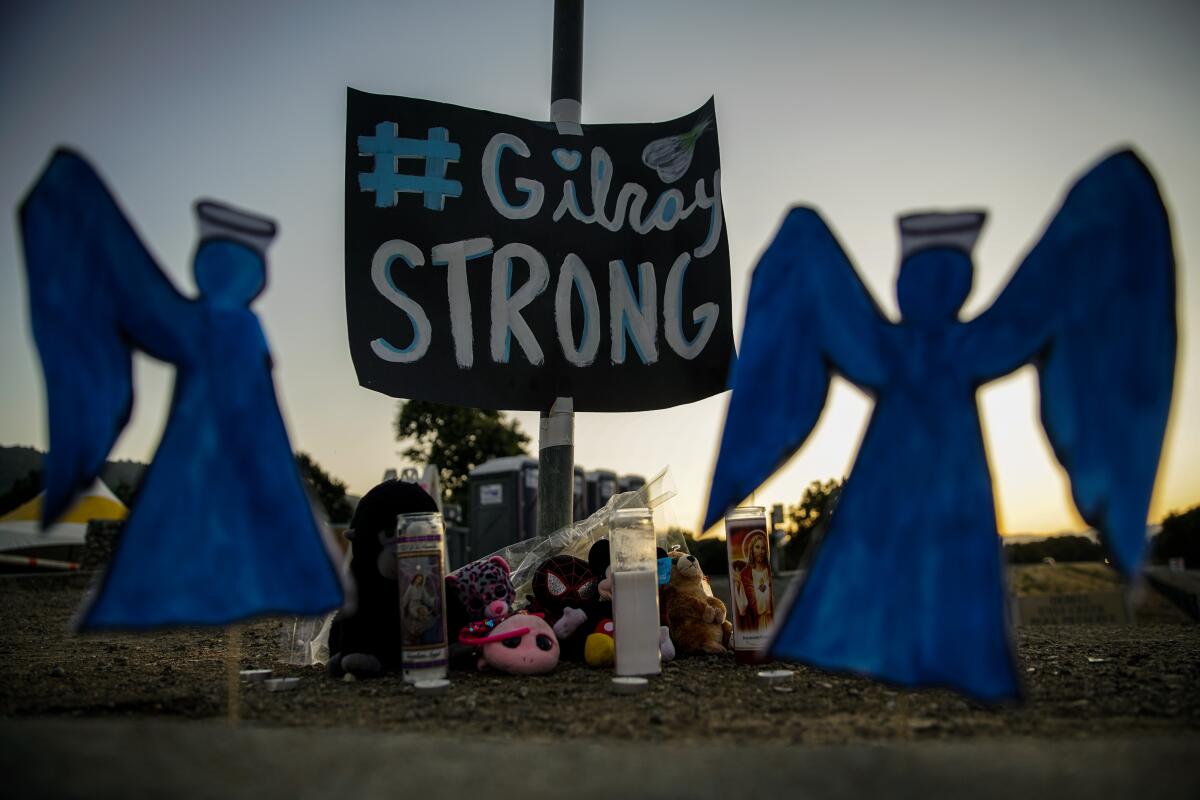

Hundreds gathered Monday night in Gilroy to grieve together over the killings Sunday of three people at the city’s annual garlic festival.

As the investigation continued into Tuesday evening, about a hundred of Keyla Allison Salazar‘s classmates and family gathered in San Jose to remember her. Some wore white shirts with the words “I love you Keyla” and “Rest in paradise” stenciled in blue.

Salazar, 13, was killed in the shooting along with Stephen Romero, 6, of San Jose and Trevor Deon Irby, 25, of Romulus, N.Y.

Among those who attended the vigil was Katiuska Pimentel, who delivered a message from Keyla Salazar’s mother.

“Keyla was a beautiful child who cared about people, who cared about animals,” Pimentel said. “We’re in pain that we lost her.”

Montero reported from Walker Lake, Vives from Gilroy, and Tchekmedyian and Winton from Los Angeles. Times staff writers Laura J. Nelson and Matthew Ormseth contributed from Gilroy, and Hannah Fry, Alex Wigglesworth, Hailey Branson-Potts and Alexa Diaz from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.