High-stakes legal battle looms in California boat fire that killed 34

Owners of boats in which people are hurt or killed succeed about half the time in winning court rulings that protect them from huge damage awards, according to a maritime legal expert.

Tulane University maritime law professor Martin J. Davies said the Limitation of Liability Act of 1851 could shield the owners of the California diving boat Conception, in which 34 people perished, from significant damages.

“It might,” Davies said. “It might.”

In a petition filed Thursday, attorneys for the owners of Truth Aquatics Inc., Glen Fritzler and his wife, Dana, cited the 1851 law in asking a judge to eliminate their financial liability or lower it to an amount equal to the post-fire value of the boat, or zero.

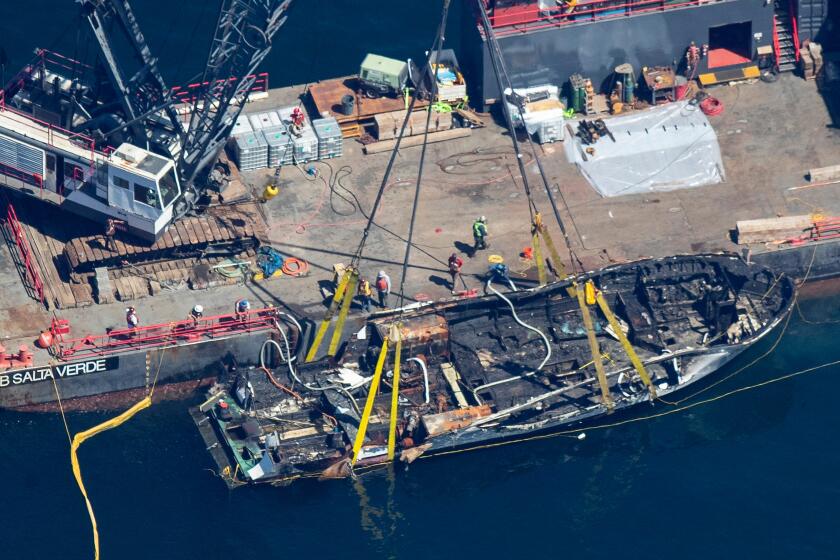

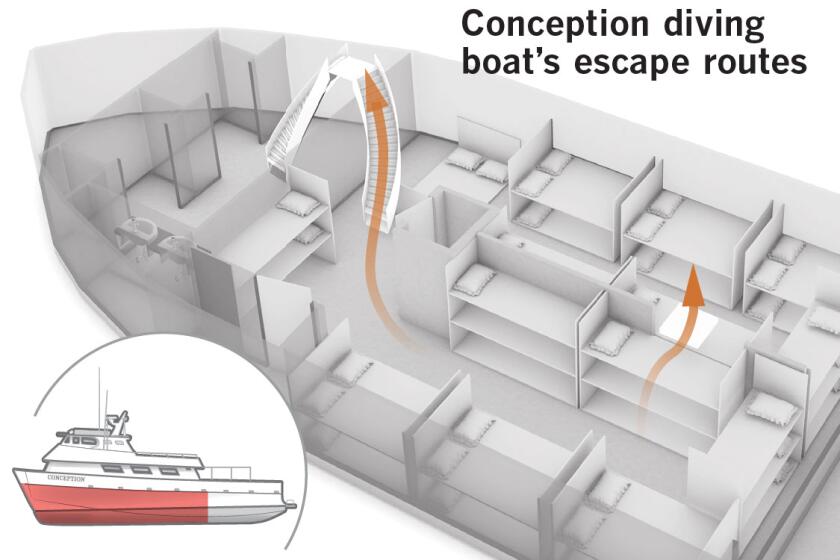

A commercial diving boat caught fire near the shoreline of Santa Cruz Island, Calif., early Monday. Many aboard the boat were believed to be sleeping below deck when the fire broke out in the pre-dawn hours.

The law, passed to spur American shipbuilding at a time when Great Britain ruled the seas, allows shipowners to sharply limit liability for accidents if there is no evidence the owner had any knowledge of the problem that caused the mishap.

The case is before U.S. District Judge Percy Anderson, a former federal prosecutor appointed by President George W. Bush.

If a fire similar to the fatal Labor Day fire that engulfed the 75-foot vessel occurred on land, the owners would bear responsibility for any negligence, an amount that could exceed $100 million.

But the maritime law limits liability to the value of the vessel after the accident.

Some maritime legal experts said the large number of casualties on the California boat and widespread publicity about the disaster might make a federal judge wary of granting the owners the protection of the law.

Agents served warrants at Truth Aquatics’ Santa Barbara headquarters, officials said. Investigators want training, safety and maintenance records.

Daniel O. Rose, a plaintiff’s maritime lawyer in New York, said it is generally difficult for owners to prove in today’s era of instantaneous communication that they “didn’t have knowledge or constructive knowledge of the fault.”

“I would not want to give [the Limitation of Liability Act] short shrift,” Rose added. “It is a real defense, and we still don’t know what all the facts are.”

But he predicted a judge would be “more likely than not” to decline to limit damages in the high-profile case.

Legal analysts said the owners would lose the protection of the law if they failed to train the crew properly or maintained equipment they knew was faulty.

But even if a judge refuses to limit liability, the owners already have obtained a legal advantage by their filing. It forces victims’ families into federal court, where a single judge, not a jury, will decide the petition.

The passengers of the Conception dive boat ended their second day in the waters off the California coast with a nighttime swim, exploring a lush, watery world populated with coral and kelp forests.

If the owner is not shielded from wide damages, the judge could decide to keep the lawsuits in federal court or allow them to be transferred to state court. State courts are considered more favorable venues for plaintiffs in personal injury and wrongful-death cases.

“Typically what claimants have to do in cases like this is show some fault on the part of the shipowner, show there was something wrong with the ship that the owners should have fixed or there was a systemic fault,” Davies said.

He said the law was invoked by the owners of the Titanic to limit liability. A court determined the cause of the disaster was a navigational error by the captain, not a flaw the owners should have known about, and the liability of the owners was limited to the value of the life boats that did not sink.

The Limitation of Liability Act applies to vessels used to navigate the ocean, lakes and rivers, including canal boats. The Supreme Court in 2005 defined vessels as watercraft capable of maritime transportation, even if transportation was not the vessel’s main function.

At the time the law was passed, owners of vessels were likely to lose contact with their ships for long periods of time. Today, owners usually are in close contact with their vessels, making it more difficult for them to argue they were unaware of dangers, legal analysts said.

Michael Karcher, a Fort Lauderdale, Fla., maritime lawyer and adjunct professor at the University of Miami, said that if a boat owner hired a poor crew or did not properly train employees, the owner would not be entitled to the limit on damages.

Claimants could seek emails and other communications to show that the owner knew of problems on the boat that contributed to the deaths, he said.

“Owners are a lot closer to their vessels and their operations than they were 50 years ago or 100 years ago or even 20 years ago,” Karcher said.

The more involved the owner was in the vessel, the more difficulty the owner will have in limiting liability, he said.

The passengers of the Conception dive boat ended their second day in the waters off the California coast with a nighttime swim, exploring a lush, watery world populated with coral and kelp forests.

Stevan C. Dittman, a New Orleans-based maritime lawyer who also teaches at Tulane, said watercraft owners regularly invoke the liability limit, even when only a single member of a crew is injured. Owners of jet skis even invoke it, he said.

Some legal commentators condemned Truth Aquatics for filing its petition with the court last week while the disaster was so fresh.

The company, in a posting on Instagram, called the suit “another unfortunate side of these tragedies.”

“This wouldn’t be something that we as a family would even consider, yet when something like this happens, insurance companies and numerous stakeholders convene and activate a legal checklist,” the company said. “The timing is on them.

“Our hearts and minds are on the tragedy and finding answers.”

A preliminary investigation into the boat fire has suggested safety deficiencies aboard the vessel, including the lack of a “roaming night watchman” who is required to be awake and alert passengers in the event of a fire or other dangers.

The company described itself as a small, family-run business that in 45 years never had an “incident.”

In addition to having to defend itself from civil lawsuits, the company or its employees could face criminal charges under a federal law established in the age of steamships dubbed “seaman’s manslaughter.”

That law has been applied aggressively during the last few decades.

Although the investigation remains in the early stages, federal prosecutors have been at the disaster scene preparing to assist U.S. Coast Guard criminal investigators and keeping tabs on the unfolding probe.

On Sunday, the FBI, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, and the Coast Guard served warrants at the Santa Barbara headquarters of Truth Aquatics seeking training, safety and maintenance records.

The theory, a good Samaritan said, was that the fire started in the galley, where cellphones and cameras had been plugged in to charge overnight.

The maritime criminal law requires a vessel’s crew, owners and corporate officers to do everything possible to protect the lives of people on board.

That law was used last year in Missouri by federal prosecutors to charge a duck boat captain and two executives of its management company in connection with 17 deaths when the amphibious craft capsized in a storm. In that case, Coast Guard investigators built the case for criminal negligence against the captain and two managers at Ripley Entertainment in Branson, Mo.

Philadelphia-based attorney Robert Mongeluzzi, a maritime-law expert, said seaman’s manslaughter was unusual in that a federal prosecutor needed to find only “negligence,” as opposed to gross negligence, to obtain a conviction. Mongeluzzi represents some of the victims’ families in the Missouri duck boat incident.

Seaman’s manslaughter became the law of the land after a series of steamboat disasters killed hundreds of people in fires and boiler explosions.

In 1838, Congress approved legislation that captains and crew could be held criminally liable if anyone on the vessel died as a result of their misconduct, negligence or inattention to duties. The penalty is up to 10 years in prison.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.