California schools can no longer suspend K-8 students for using phones. Will this help or hurt learning?

In middle school, Anthony Avila would stand up in class, talk to friends when he wasn’t supposed to and sling his legs across a second chair. His disruptive behavior got him sent to the office a lot, where he would sit in silence, often stewing.

In high school, Avila’s math teacher used another tactic. She kept him in class when he acted up and opened her room early so they could talk. When other teachers still sent him to the office, the staff at Huntington Park Institute of Applied Medicine was kind. They asked him to run errands or make copies. Counselors helped him with school work.

“I ended up getting good relationships ... so I felt like I had to respect them and do my work,” said Avila, now 18, whose behavior and grades slowly improved.

This is the kind of scenario that educators and lawmakers hope will unfold across California as schools embark on a new era of student discipline.

A law signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom prohibits suspensions for “willful defiance” in grades four and five and bans it in grades six to eight for five years. Actions such as chewing gum, playing with a phone, tapping feet, napping, mouthing off or being out of uniform may still bring consequences — but it won’t be suspension.

Many educators and public interest groups pushed for the law because research shows that black, Native American and Latino students bore the brunt of harsh discipline practices. Suspensions failed to transform students’ behavior and they missed classes, fell farther behind and became more likely to drop out of high school. Now educators are embracing more supportive practices, such as the ones that helped turn Avila around.

The alternatives, however, require an abundance of school-based support, teacher training and an infrastructure of counselors that are not available at every school. Without help, teachers become frustrated and classrooms are disrupted and demoralized by unruly behavior.

Los Angeles schools, which banned willful defiance suspensions in all grades in 2013, offer a real-time case study on the issue — and the results are mixed.

“Shifting away from punitive discipline is one piece in actually confronting implicit and explicit bias in our schools,” said Ruth Cusick, a staff attorney at Public Counsel, which advocated for the change in state law. But, Cusick said, “The real work has to be focused on what tools and supports are needed for our schools to truly transform school climate.”

The depth of the discipline problem

In the 2012-2013 school year, the Los Angeles Unified School District suspended 16,600 students, including nearly 3,700 for “defiance only.” Almost one-third of those suspended were black students, although they made up less than 10% of the student population.

Last school year, LAUSD suspensions were down to 6,400. The drop reflects a decrease in suspensions for willful defiance and also for violence, drug-related incidents and weapons possession, serious actions that are still grounds for suspension. Even with the decrease, black students still comprised one-third of all suspensions.

There are many reasons for the racial divide in discipline, including differences in family income and teacher-reported behavior, education experts said.

Annamarie Francois, executive director of Center X, an educator development and support unit in the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, said that often teachers don’t understand their students’ backgrounds or potentially the trauma they experience. Bias can also play a role.

As a student at Crenshaw High School, Timothy Walker, now 22 and a senior at San Francisco State University, often saw his peers getting suspended for putting their heads down or refusing to participate in classroom activities.

Walker, who is black, said he noticed white teachers tended to opt for the most punitive outcomes, rather than reacting with compassion or understanding. In contrast, he said, with the black or Latinx teachers, “if there was an issue, it wouldn’t go all the way to 100.”

How the suspension ban can fall short

Walker was still a student when the ban on willful defiance suspensions took effect in Los Angeles. But he was disappointed in its aftermath.

Students knew they wouldn’t be punished in the same way. But teachers did not appear to have the tools to address the underlying reasons for the behaviors, or build relationships and connect with students, he said.

Nena Anderson, a former health teacher at Crenshaw, said that in one of her classes last school year a number of upperclassmen were constantly on their phones, disrupting class and using profanity. She relied on sending kids out to keep order. However, she said, the dean or security officers were often occupied and could not immediately escort the student out.

Students were supposed to go to the library to work or receive one-on-one attention from a dean or behavior specialist. Often, though, there were too many students to give individualized attention to, she said.

Crenshaw school administrators declined to comment about Walker’s and Anderson’s experiences via a district spokesman, who said the high school’s “approach to discipline focuses on prevention and intervention strategies.” By 2016, a campus team had been trained in restorative justice practices, including community building. In addition, the school has a full-time restorative justice advisor and wellness center that offers mental health services.

Scott Martin-Rowe, who taught English language learners at a high school on the Miguel Contreras campus last year, said he dealt with a group of freshmen who repeatedly disrupted class. They would arrive half an hour late or skip out early — if they showed up at all. The group would sit together even though they were assigned seats apart. Students were constantly on their phones.

“You’d ask them to put them away, and they would do it for 30 seconds,” Martin-Rowe said. “Stuff like that, it wears you down.”

The students weren’t doing any work, and they were behind. Martin-Rowe called their parents, connected with their homeroom teachers, and discussed strategies for helping them with other teachers, counselors and the principal many times. Some of the students were referred to the school’s full-time psychiatric social worker or outside therapy.

“A lot of stuff just didn’t work with them,” he said.

Martin-Rowe said his students face “all kinds of issues” that can’t necessarily be addressed in school, such as trauma related to immigration, poverty and gang violence.

Los Angeles Unified’s goal since banning willful defiance suspensions has been to apply a “trauma-informed” lens to teaching, said Pia Escudero, executive director of health and human services for the district. That means considering the difficulties students have outside of school when handling their behavior in school.

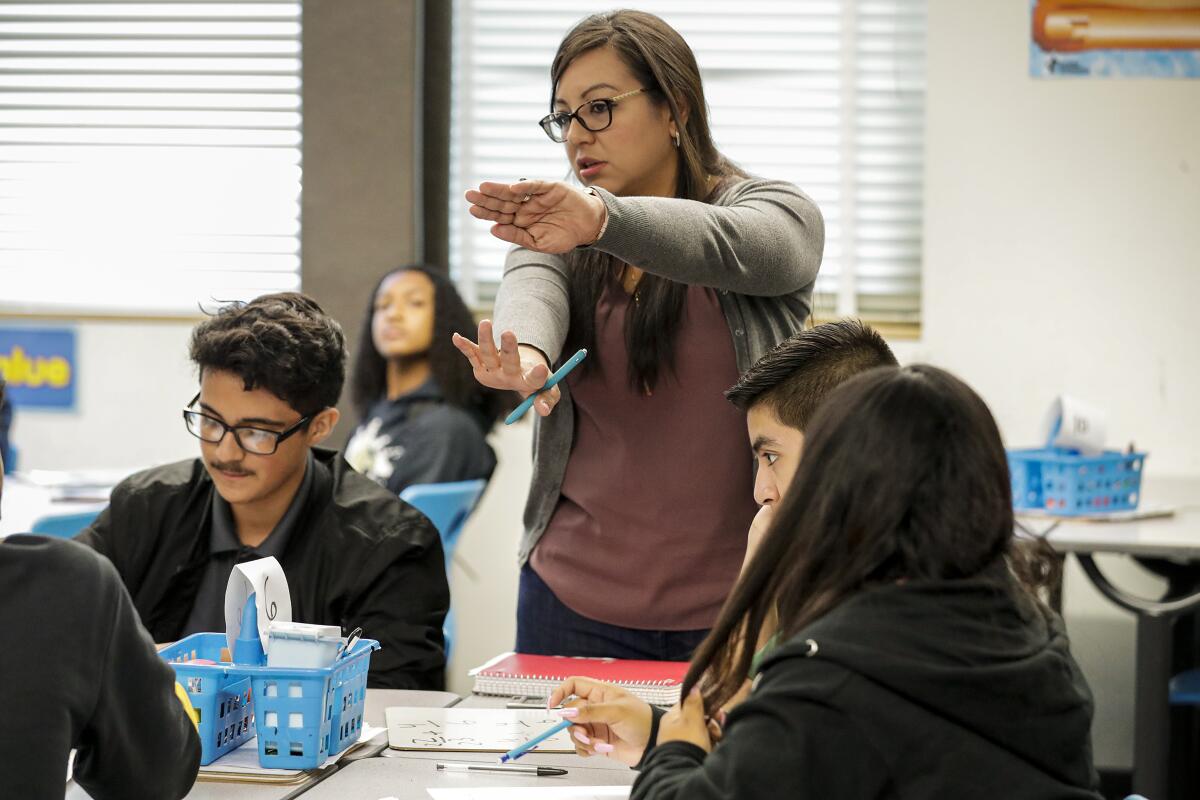

Eugenia Plascencia, a ninth-grade math teacher at Social Justice Humanitas Academy in San Fernando, checks off a list of needs when a student is being disruptive.

“I usually try to get to the bottom of, did something happen this morning? Are you hungry? … If a kid’s hungry, if a kid hasn’t slept, they’re really not going to be able to focus,” said Plascencia, who said that growing up in nearby Pacoima has helped her empathize with students.

By the end of this school year, Escudero said, teams at every school will have received training on how to help students identify and manage feelings to avoid or resolve harmful behavior.

For students who need additional help, Los Angeles Unified has allocated more money, including a little over $1 million this school year, to on-campus psychiatric social workers and attendance counselors. But district officials acknowledge they don’t have the resources to provide sufficient supports at every school.

“I do hear that schools are saying, ‘It’s not enough, we need more,’” Escudero said.

Building relationships

Anthony Avila’s Algebra I teacher used classroom techniques that exemplify the goals of Los Angeles Unified’s discipline policies.

Patricia Matos seats students at tables of four. Every student has a job to help one another and maintain peace: facilitator, task manager, resource manager and reporter. The students work together to solve problems while Matos walks around answering questions, instead of calling on students in front of their peers.

A teacher’s aide as well as a resource teacher, who focuses on special education students, are also on hand to manage the class of 38. In addition, the Huntington Park campus has benefited from being a pilot school with flexibility to try new approaches to educating underserved students. The school has a robust support staff, including a psychiatric social worker, a school psychologist, an attendance counselor, two college counselors and two academic counselors.

After Avila failed most of his classes in his first semester of freshman year, Matos was part of his student support team — along with his mother, the principal and his counselor — that came up with a plan to get his grades back on track. Not only did he graduate in June, he spoke at the school’s commencement and is now pursuing studies at Los Angeles Trade Technical College.

“That really, I guess, did it for him to realize, ‘Hey, like I’m not alone here,’” Matos said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.