Saddleridge fire’s rapid spread left residents little time to get out

The sensation was so familiar — the crackling wood, the helicopter rotors drumming through dread and adrenaline, dry wind and smoke and fire lighting the sky blood red.

Jackie Herrera was watching the flames in the hills above her home in Sylmar. She had known the Santa Ana winds were coming, and what that inevitably means this time of year: fire somewhere, maybe many places.

But she couldn’t believe it was here at this very spot again, where her home burned to the ground 11 years ago.

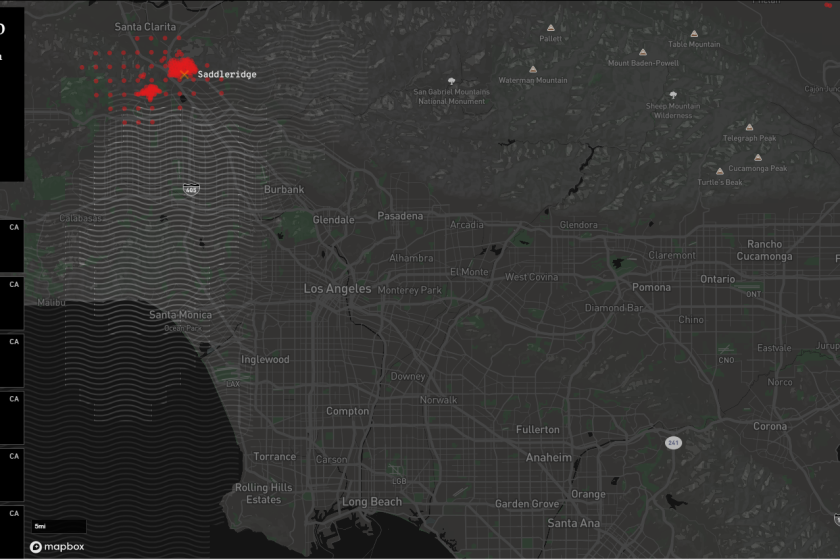

The Saddleridge fire ripped through the hills rimming the north edge of the San Fernando Valley on Thursday night and Friday, burning at least 31 structures, closing freeways and forcing the evacuations of thousands.

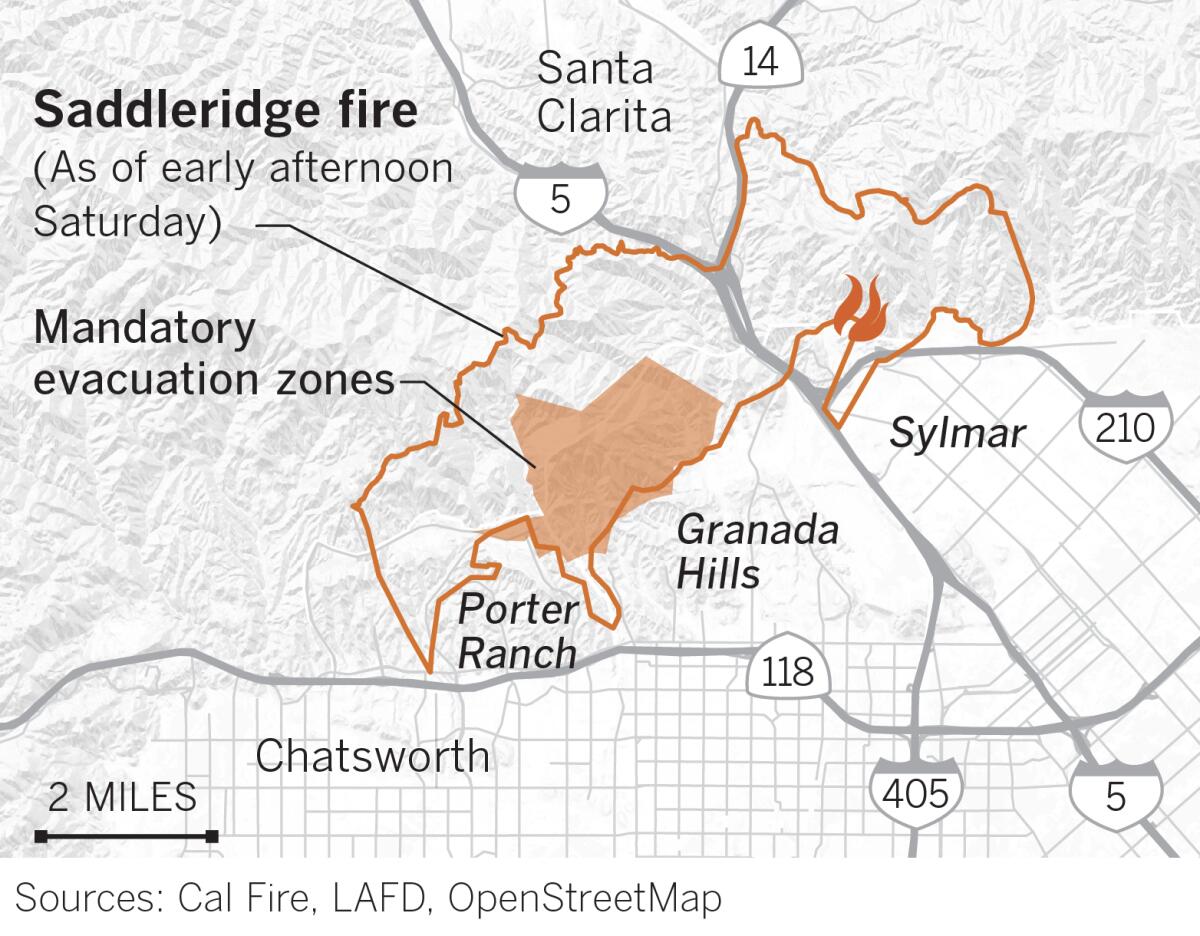

Peak winds above 50 mph drove embers hundreds of yards in front of the flames. The fire hopscotched west from Sylmar — leaping over the 5 Freeway into Granada Hills and Porter Ranch, at times consuming 800 acres an hour.

More than 1,000 firefighters from multiple agencies fought the sprawling blaze night and day, deploying eight helicopters and amphibious fixed-wing “super scoopers.” Ground crews manned bulldozers to cut containment lines into nearby hillsides. At least one air tanker blanketed fire retardant across the ridges between Granada Hills and Porter Ranch.

By late morning Friday, the Saddleridge fire in the San Fernando Valley had exploded to 4,700 acres and burned 25 homes.

By Friday afternoon, 7,500 acres had burned.

L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti and Gov. Gavin Newsom both issued emergency declarations. The governor’s office said it has obtained a federal grant to help offset the costs of fighting the Saddleridge fire and others in the state.

Mandatory evacuations have been issued to roughly 23,000 homes north of the 118 Freeway from Tampa Avenue west to the Ventura County line. Officials warned that other communities near the fire need to be ready to leave at a moment’s notice.

Deputy Chief Jorge Rodriguez of the Los Angeles Police Department said the city sent alerts, used police public address systems and sent dozens of officers knocking on doors as the fire swept west. “A lot of people left, but some didn’t,” he said. “We aren’t going to force people to leave.”

It was depressingly familiar territory, not just because of the Sayre fire in Sylmar that burned 489 homes in 2008 but also the Aliso Canyon gas leak four years ago that forced the evacuation of 11,000 people in and around Porter Ranch, and the fire that destroyed 13 homes in Porter Ranch in 1988.

With the unrelenting wind, warm temperatures and low humidity, officials said they expect it will take days to get the blaze under control.

“Nobody is going home right away,” said Los Angeles Fire Chief Ralph Terrazas.

One firefighter suffered a minor injury to his eye while battling the blaze, and a man in his late 50s died after suffering a heart attack while talking with firefighters early Friday, officials said.

Friday afternoon, the wind was pushing the fire west into residential neighborhoods in Porter Ranch and farther west to less-populated areas approaching Rocky Peak Park near the Ventura County line, said Capt. Branden Silverman, an LAFD spokesman.

Porter Ranch is “basically the hot spot right now,” Silverman said. “We’re trying to keep it boxed in above the 118 Freeway. Obviously that’s a good fire break for us, but if the winds shift to the south, then that would be into Chatsworth.”

Silverman said the wildfire is similar to the 2008 Sayre fire, which leveled the Oakridge Estates mobile home park and was one of the most destructive wildfires in Los Angeles history.

Porter Ranch is no stranger to disasters after being battered by brush fires, earthquakes and a major natural gas leak. The latest began Thursday night when spot fires ignited homes and sent hundreds of residents fleeing.

The Saddleridge fire broke out about 9 p.m. Thursday on the north side of the 210 Freeway.

By early Friday, it was at the Oakridge community’s door again. Residents, including Herrera, were evacuated, and many waited in their cars nearby watching the flames’ hypnotic destruction.

“I can’t quite pull myself away,” Herrera said. Her cat Satchel, who survived the fire 11 years ago, was in her car. “I don’t want to go through this again, and he doesn’t either,” Herrera said.

Danny Rios, 59, lives in Oakridge with his father. His parents lost their home there in 2008 and Rios had lost his own, but they decided to return for the quiet natural setting. His mother has since died, and he didn’t know how his father might cope with another potential loss.

“It’s a horrible, horrible feeling to lose your home, to lose everything in it,” he said.

In Granada Hills, retired nurse Patricia Strucke, 79, watched the flames burn in Riverside County on the 9 p.m. news and felt sick thinking of the families some 90 miles away whose homes were at risk.

“Your house can be gone in five minutes,” she remembered thinking. “I can’t watch this. It’s too horrible.”

The fast-moving Saddleridge fire in the San Fernando Valley has charred dozens of homes, closed freeways and forced thousands to flee.

She walked into the kitchen and put her empty glass in the sink. Then, she looked up. Through her kitchen window, she saw a glowing red semicircle licking at the hills.

“My God!” she said. “There’s a fire in Sylmar.”

She rushed to wake her husband, Edward, 77, who uses a wheelchair, warning him they may need to evacuate. But it was still a good distance away, so she kept monitoring it.

Around 11:30 p.m., as the flames chewed down a hill about 200 yards from their home, Patricia barged into the couple’s bedroom. “Get up!” she told her husband. “We’re going.”

Edward slipped on shoes and got into his wheelchair. Outside, ash rained down on the home they’d lived in for 45 years. As they drove away, Patricia realized she’d forgotten her husband’s most important medication, an anti-coagulant, but it was too late to go back.

She thought, too, of the many memories they’d made inside the home.

She thought of her two grandchildren, now teenagers, and how they learned to swim in their backyard pool. She thought of the times they came over after school to work on homework or when they helped tend her tomato plants. “Am I going to have a home?” she thought.

It has long been a dilemma of many wildfires: Where to shelter large animals when the flames come roaring?

Unsure of where to go, the couple pulled into a Ralphs parking lot to wait. Edward called the police, asking if they knew of any evacuation centers. Not yet, they said. When he called back, officials directed them to the Granada Hills Recreation Center. They arrived around 1:30 a.m. and spent the night on cots set up by the Red Cross.

About 8:30 a.m. Friday, a neighbor called to say that he’d managed to get close to their house. Everything was ashy and the air was still choked with smoke, but the home seemed safe, he told her. Relief washed over Patricia. But she said she knows embers can change things quickly.

About 9:30 a.m., a Red Cross volunteer handed Edward a blue mask to block the smell of smoke. Another volunteer waved goodbye, saying her shift had ended. “Bye!” Edward said, waving. “No offense, but I hope I never have to see you again.”

Sitting nearby, Amelia Peters, 78, was a ball of nerves. She’d been in a panic the day before the fire after her landlord had given her a 60-day eviction notice. Worried about her future, her blood pressure spiked to 180 on Thursday, she said, and her husband took her to the emergency room.

She returned home that night only to find herself monitoring flames from her windows. “I’m packed and ready to go as soon as they give evacuation orders,” Peters texted a friend. They left around 4 a.m. and drove to the rec center with their chihuahua, Bambi.

She left behind her collection of blue-and-white ceramics and all of the paintings her three children had made over the years — her own little gallery, she said. But most of all, she was worried about her husband, a music producer, who didn’t want to leave all of his equipment and decided to wait it out at home.

Some L.A. Unified parents, teachers and union leaders complained of hectic, uncomfortable conditions on campuses and criticized the decision to keep many schools open.

At the evacuation site Friday morning, Peters looked down at her right arm, still bandaged from a blood draw at the hospital. “Yesterday I went to Kaiser, because I was so stressed,” she said, laughing softly. “Now, I’m way more stressed.”

Kim Thompson of Granada Hills evacuated at midnight and had enough time to return for a bottle of wine. Her neighbors were less willing to leave: “Up here, we’re stubborn. My neighbors are spraying their roofs right now.”

Support our journalism

A little after 1 a.m., Thompson heard from a friend that fire crews were allowing two homes on Jolette Avenue to burn to the ground. She thought back to the Aliso Canyon evacuation and the Sayre fire, which burned to the very edge of her cul-de-sac.

“We’ve been through a lot, but we choose to live here,” she said.

“You’re on edge. You think you get used to it,” Thompson said, eyes watering in the smoke, “but you can’t really get used to this.”

Times staff writers Hannah Fry, Colleen Shalby, Matthew Ormseth, Leila Miller, Matt Stiles and Alejandra Reyes-Velarde contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.