Robert Fuller’s death brings enormous public scrutiny of a brief life of struggle

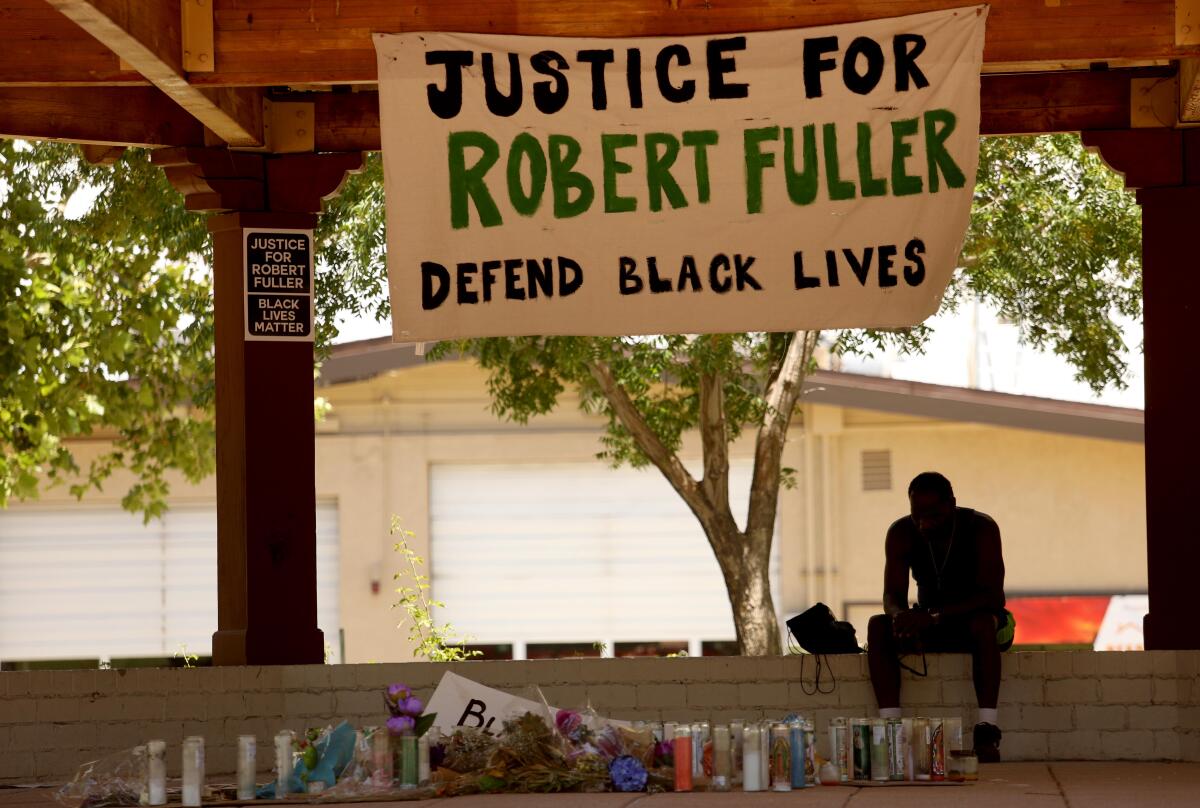

On June 10, Robert Fuller’s body was found hanging from a tree outside Palmdale City Hall. His death came in the middle of the George Floyd protests and a week after Malcolm Harsch, another Black man, was found hanging from a tree in Victorville, less than 50 miles away. Their deaths shed light on the concerning rise in suicides among Black Americans.

Since the early morning hours of June 10, when a passerby found the body of a young Black man hanging from a tree near Palmdale City Hall, the brief life of Robert Fuller has come under a microscope.

Local authorities deemed his death a suicide, linking it to isolation brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. They walked back the determination days later as residents demanded an investigation, in disbelief that when a Black man was found hanging in a public square, the authorities had so quickly ruled out foul play.

Protests against racism were cresting in Southern California and across the nation. Much of the American public was approaching the word of law enforcement with new skepticism and the circumstances of Black men’s deaths with more scrutiny.

RELATED: Suicide prevention resources

Some residents of the Antelope Valley, invoking the region’s history of hostility toward Black people, voiced fears that Fuller had been lynched. Hundreds of thousands of people signed a petition demanding a more thorough investigation.

“My phone’s constantly ringing about concerns about this,” Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva told reporters. “It means a lot to a lot of people.”

But for all the fears of what Fuller’s death could have been, it became clear last week it came at his own hands. The Los Angeles County medical examiner-coroner ruled it a suicide, and Sheriff’s Department investigators said they recovered medical records documenting a history of suicidal behavior. A separate autopsy commissioned by Fuller’s family found no signs of foul play.

Nor, the family’s attorney and the authorities have concluded, was his death connected to that of his half-brother, Terron Boone, who died in a firefight with sheriff’s deputies one week after Fuller’s body was found.

With the findings of Sheriff’s Department investigators, interviews with Fuller’s friends and a review of public records, a portrait emerged of a man whose 24 years of life were never easy, beginning with the death of his mother in childhood and continuing through a series of hospitalizations for apparent mental illness.

It is a story that has been thrust beneath a magnifying glass of enormous public scrutiny. Had Fuller not died “when everything was at a boiling point,” one of his friends, Victor Adeyokunnu, said in an interview, “it probably wouldn’t have even made the news.”

“Personally,” he added, “I’m thankful he didn’t go silently.”

Fuller grew up in the Antelope Valley’s two biggest cities, Lancaster and Palmdale, about an hour’s drive and a mountain range away from Los Angeles proper. Bordered by the San Gabriels to the south and the Tehachapis and Sierra Pelona to the west, the Antelope Valley is home to a growing number of Black families who have left Los Angeles for a lower cost of living — and for many, the chance to own a home.

It is sprawling, sun-baked country, where housing developments and strip malls alternate with stretches of desert populated only with gnarled Joshua trees. Like the air that hangs heavy and shimmering in the heat, there is a sense of stagnancy here, of “not going forward or backward,” Chad Bellows, one of Fuller’s friends, said in an interview.

Fuller was just 8 years old when he lost his mother. In 2004, she was under anesthetic for a procedure when her heart rate and blood pressure began to plummet, a coroner’s report said. She died within the hour, 43 years old. Many years later, one of Fuller’s sisters would tell investigators he struggled with depression stemming from his mother’s death, according to a coroner’s report. In time, he’d tattoo her name — Terri — on his right arm.

Fuller, the youngest of his siblings, lived with his father, then a family friend. After the family friend died, he was raised by his sisters. “Robert was only three years younger than me,” one of the sisters, Angel Magee, said at his funeral, “but Robert was definitely my first baby.”

His friends recount a fun, if listless, adolescence: They ranged all over Palmdale and ventured into Los Angeles to skateboard, although Fuller, doomed by big feet and a lack of coordination, soon gave it up, Bellows said. They danced at a local church on Tuesday nights — “that’s how bored we were,” Bellows said — the style changing from break dancing to pop-locking to krumping as they grew up.

Fuller went through a number of phases, the most memorable being his punk rock chapter, Bellows recalled. He wore studded belts, tight jeans and hoodie shirts, and he straightened his hair and dyed it red. Magee said her brother “begged his auntie to perm his hair,” then refused to swim in the pool for fear of getting it wet.

After finishing high school in 2016, Fuller wanted to work as a fashion designer or graphic artist, his friends said. Like most kids from Palmdale, he envisioned leaving it for someplace else. “Everybody grows up here with some kind of dream, but it’s always outside of the city,” said Justice Bryant, a friend of Fuller’s who now lives in Houston.

Fuller split time between Nevada, where his father lives; Arizona, with his sisters; and California. It was around this time, according to Sheriff’s Department investigators and court records, that Fuller began showing signs of mental illness and got into some trouble with the law.

In January 2017, Fuller was hospitalized in Arizona and diagnosed with auditory hallucinations after saying he wanted “to put a gun to his head,” Sheriff’s Cmdr. Chris Marks said. He reported hearing voices telling him to kill himself in 2019, and he was treated that year at hospitals in California and Nevada. During this same time period, Fuller served brief stints in Los Angeles County jails after being convicted of vandalizing a church and obstructing a police officer, court records show.

For a year, he lived off and on at a shelter for homeless youths in Las Vegas, Marks said. A coordinator at the shelter, the Shannon West Homeless Youth Center, told an investigator that Fuller “would attempt to live with his father, but when it didn’t work out, he would return to the shelter,” a coroner’s report said. A representative for the shelter declined to comment, citing medical privacy laws.

In February, Fuller tried to light himself on fire in Las Vegas, Marks said. He left the Las Vegas shelter for good and was later reported living in Reno, homeless, the coroner’s report said. He traveled to Arizona to see his sisters and returned to California on June 4, coroner’s records say.

RELATED: The need for mental health help during the pandemic

Fuller was last seen alive at a 7-Eleven store around 8 p.m. on June 9. He was wearing a purple sweatshirt and a red backpack, filled with clothes and toiletries.

At 3:40 a.m. the next morning, a homeless person walked into a fire station near Palmdale City Hall to report a body in a tree.

Late last month, mourners shuffled past a gold casket beneath the pulpit of Living Stone Cathedral of Worship in Littlerock, a tiny community southeast of Palmdale. Some knew Fuller well; others, not at all. Ushers passed out cards with Fuller’s life story on the back. It was brief, as any life story of a 24-year-old would be.

No matter how he died, no matter what the doctors who probed his body or the detectives who scoured his life story found, it does not change this immutable fact, Hicks, the family’s attorney, said in an interview: “He was a young man, 24 years old, still trying to find his way.”

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at (800) 273-8255. A caller is connected to a certified crisis center near where the call is placed. The call is free and confidential.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.