Homeless people in L.A. increasingly are taking their lives by hanging

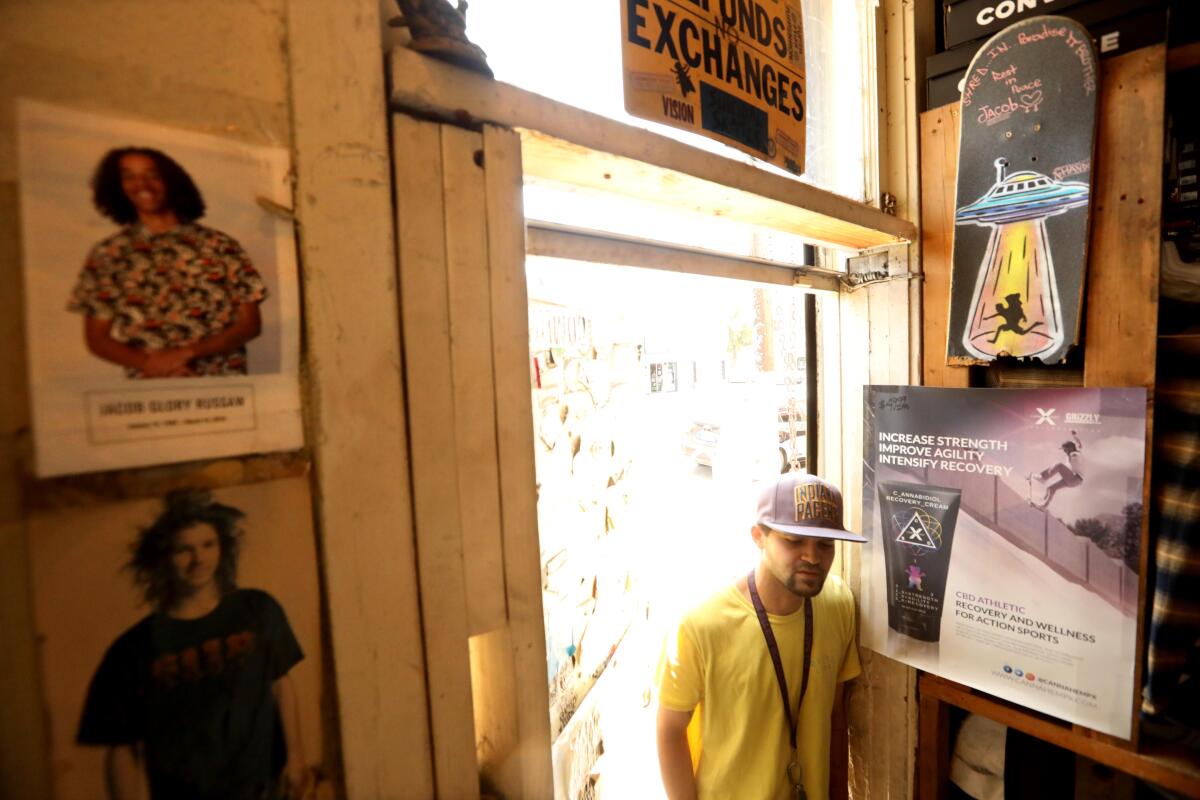

He was a talented skateboarder on the verge of landing a company sponsorship. Dressed in loud Hawaiian shirts or tracksuits, his shock of hair untamed, skater style, Jacob Glory Russaw practiced ollies and kick flips for hours at the Venice and North Hollywood skate parks or in the streets of East Hollywood. Then he made up his own tricks.

“Skating is my life,” the 20-year-old wrote on his Instagram page. “It’s like breathing it makes me feel like I can do something [in] life.”

But Russaw was also struggling. He was young and Black and living at a homeless housing agency, working his way out of a fractured upbringing. And he had lost his room there, something that even some of his skater friends didn’t realize.

They learned only after he had died by hanging.

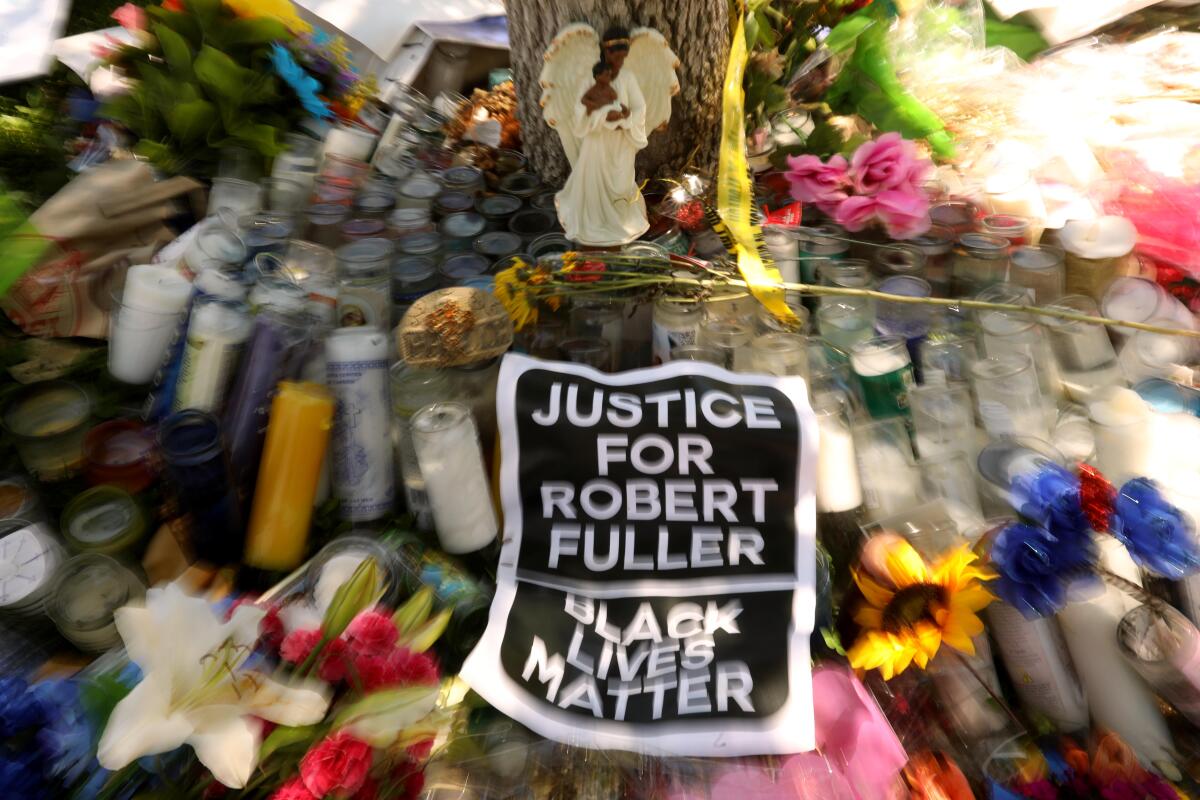

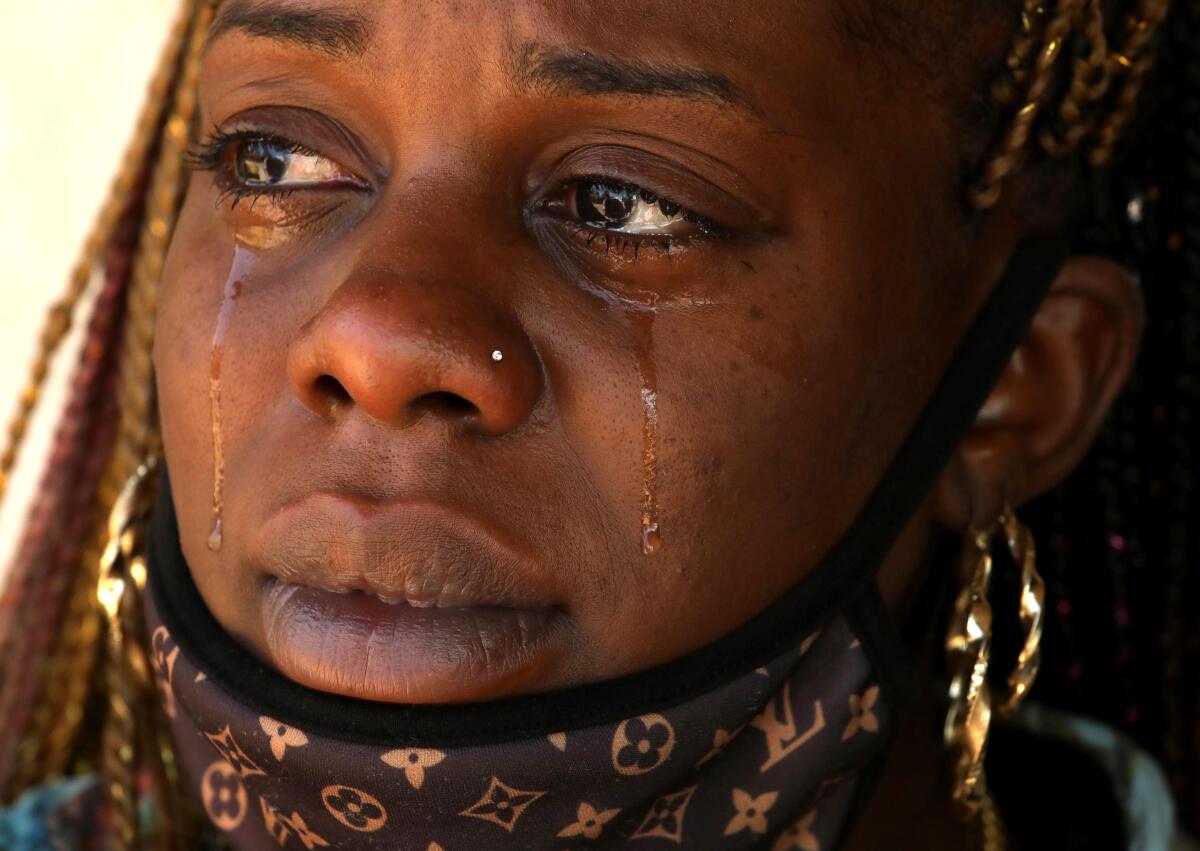

When two other Black men — Robert Fuller, 24, and Malcolm Harsch, 38 — were found hanging from trees in two Southern California cities this spring, their families disputed suicide findings. Black people are far less likely to end their lives than white people, and the hangings, in the midst of protests against police violence, conjured up America’s ugly legacy of lynchings of Black men, which authorities sometimes labeled suicides to cover up for white police and mobs.

On June 10, Robert Fuller’s body was found hanging from a tree outside Palmdale City Hall. His death came in the middle of the George Floyd protests and a week after Malcolm Harsch, another Black man, was found hanging from a tree in Victorville, less than 50 miles away. Their deaths shed light on the concerning rise in suicides among Black Americans.

But further investigation turned up no foul play. Both men had a history of homelessness: Fuller, who had a previous suicide attempt, had lived on and off at a youth shelter in Las Vegas and was homeless in Reno before moving to Palmdale, where he died. Harsch had been living in a homeless encampment near Victorville.

And their deaths, like that of Russaw in 2018, fit into a surprising pattern. Increasingly, homeless people in Los Angeles and its environs are dying by hanging.

Over 4½ years ending in mid-June, 196 people experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County took their lives. In 2016, 40% of the suicides were by hanging; so far this year, it’s 55%, according to a Times analysis of coroner’s reports.

Many homeless people hanged themselves in public — on a freeway off-ramp or sidewalk, in an alley, field or vacant lot — but their deaths went largely unremarked.

“Homeless suicides have not been an issue,” said Mike Neely, former Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority commissioner. “I’m not sure people want to have that discussion; it goes to the heart of the neglect of people.”

As part of our Column One story on Kevin Howard’s struggle to build a life beyond the battlefield, here is a list of organizations that provide support, information and resources to veterans and others.

No one knows why someone else takes his life, but for many homeless people, a history of trauma is exacerbated by the miseries of homelessness. Authorities struggle to get mental health services into the streets, and culturally competent suicide prevention for homeless people is lacking. A firearm is the leading suicide method for men in the U.S, but homeless people don’t typically have guns.

After Harsch died, his family initially suspected he had been lynched but eventually came around to believing it was a suicide. But they also expressed disappointment in the lack of services that could have prevented his death. “The [Harsch] family is gratified to have a sense of closure that he wasn’t the victim of a lynching,” said activist Najee Ali, a family spokesman, “but the big question is why his death wasn’t investigated properly to begin with. In retrospect, we all wish there had been more homeless outreach services, especially mental health.”

Russaw’s family, too, said he should have received mental health care.

Only 19 of the homeless people in Los Angeles County who have taken their lives since 2016 were Black, and just a handful of them died by hanging. But suicides are rising among Black youths — from 2.55 per 100,000 in 2007 to 4.82 per 100,000 in 2017, according to a Congressional Black Caucus task force report on Black youth suicide released in December.

“The face of suicide has been older white men, because of the sheer numbers of more white men dying of suicide, but that’s something of a misnomer,” said Michael A. Lindsey, executive director of the McSilver Institute for Poverty Policy and Research at New York University and the congressional task force chairman.

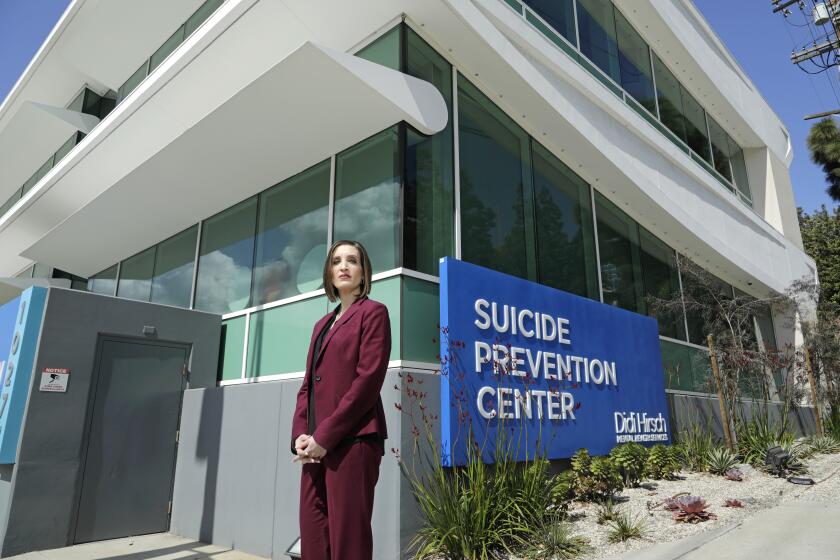

Crisis counselors at Didi Hirsch in Century City, whose job it is to reassure, now need some reassurance of their own — because the coronavirus knows no boundaries.

Several weeks before Russaw’s death, Covenant House, a youth homeless agency in Hollywood, kicked him out of its housing program. Chief Executive Bill Bedrossian said he couldn’t discuss the reason; family and friends said it was for violating program rules, including breaking curfew.

Mike Stommel, a spokesman for Covenant House said Thursday that Russaw had been temporarily “restricted” from housing but could have appealed to be allowed to come back to the organization. Stommel also said that not sleeping at the house, bullying or threatening residents or assaulting them or staff were violations that could result in a housing restriction.

Bedrossian said mental health services were available to Russaw, before and after he left housing. One of Russaw’s sisters, Candice, 33, said they should have been mandatory.

“If you don’t have mental health issues already, try being homeless,” she said.

Brayan Vargas, an employee at L.A. Skate Co. on Santa Monica Boulevard, said Russaw told him Covenant House had bagged his things, stuffed them in a closet and told him they’d given his bed to someone else.

“I found it very foul,” said Conner Nico, another L.A. Skate Co. employee who lived at Covenant House for a time. “It’s a good program in many ways, but you don’t do that to a kid who’s already down and wanted to do good.”

“We don’t see restrictions as the worst things in the world; they’re part of a process to learn you have to be accountable in life,” said Bedrossian, adding that he and the rest of the staff were especially fond of Russaw.

“Jacob was adored here, frankly,” he said.

Russaw did not broadcast his distress, said friends, who described him as fun-loving and joyful. “Anything to not have a moment of silence,” a friend said. “He masked it well.”

Russaw grew up in Watts and Lancaster with his aunt and cousins, whom he considered his mother and sisters (and are described that way here). He was a daredevil who taught himself to ride a unicycle and a ripstick, jump on a pogo stick, launch back flips on the concrete and leap off a roof into a pool. He learned to walk up a wall like a ninja warrior and tried to prank his sister Brandy Russaw, 34, into believing that he was a space alien. It almost worked, she said.

After a family fight, their mother reported Russaw to juvenile authorities, who placed him in detention, followed by foster care. At age 18, he entered Covenant House, where he earned his high school diploma — the first in his family to do so, Bedrossian said.

At a traffic light on Hollywood Boulevard, he met Hikaru Lee, 33, a foreign student from Japan who taught yoga. They snowboarded, hiked and went to the beach, and Russaw posted that he was going vegan. “Jacob was a real hippie,” said his sister Chanel Mookie Evans, 28.

Russaw enrolled at Santa Monica College but quit to work a restaurant job. His real calling was skateboarding.

He wore a skateboard bearing as a ring and sometimes practiced far into the night. At L.A. Skate Co., Russaw traded clothes he had thrifted for grip tape and skateboards to replace the ones he split grinding stair rails or performing tre flips.

“I never saw anyone do that before,” said the skate shop owner, Dave White, who videotaped him repeating the trick so he could show potential sponsors. White shot another video of Russaw skating up to the shop with the pieces of a busted board strapped to his feet with turquoise shoelaces.

“He could skate anything with wheels,” White said. “Some of the company people who came in here said, ‘Who’s that kid with the bushy hair? He’s killing it.’ He was on his way. The companies were waiting to see what he could do.”

After his ouster from Covenant House, Russaw slept at the North Hollywood skate park, a small park in Hollywood or under the lights at a Metro station, Vargas said. “The streets here are not the best,” Vargas said.

Lee had roommates and didn’t always let him stay. They argued; she said she didn’t understand what he was going through until after he died.

“I don’t know about homeless, but it affected him really bad,” she said. “He told me it’s not easy being a Black man. He felt it was not comfortable looking for a job because of his color.” Russaw hanged himself in Lee’s apartment in March 2018.

Covenant House paid for a memorial and his funeral at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City. Friends covered the slate-blue casket with his favorite skate shop stickers.

Russaw’s skateboard — painted with the insignia “Shred in Paradise Brother” — hangs on L.A. Skate Co.’s wall. At a get-together in Lancaster this summer, Candice and Brandy wore Jacob’s shirts and Evans brought one of his skateboards.

“In foreign countries, they don’t let old people and young people be homeless,” Candice said. “Especially with Black people, the village is broken. Why isn’t our government doing something?”

“He was just a kid,” Brandy said.

If you or someone you know is exhibiting warning signs of suicide, seek help from a professional by calling the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at (800) 273-TALK (8255).

Times staff writer Maloy Moore contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.