Schools in more affluent areas move faster to reopen than those in low-income communities

South Whittier schools Supt. Gary Gonzales works seven days a week to move his elementary schools closer to reopening. But the barriers are significant: He’s looking for ways to get vaccines to teachers, negotiating with the union and closely monitoring coronavirus case numbers that show that the virus is still ravaging his community, even as case numbers fall countywide.

Gonzales knows his district’s students, almost all of whom are Latinos from low-income families, are struggling under remote learning. And he knows his community is hurting — the pandemic has claimed 118 lives in tiny South Whittier. A date for bringing students back to the classroom is unclear.

“It’s all kind of wait and see,” he said.

Thirty miles away, Supt. Wendy Sinnette of the La Cañada Unified School District, which has among the lowest coronavirus rates in the county and few students from low-income families, has been focused on reopening as many classrooms as possible since November, when students in transitional kindergarten through second grade returned to campus. Third-graders will be welcomed back on Tuesday.

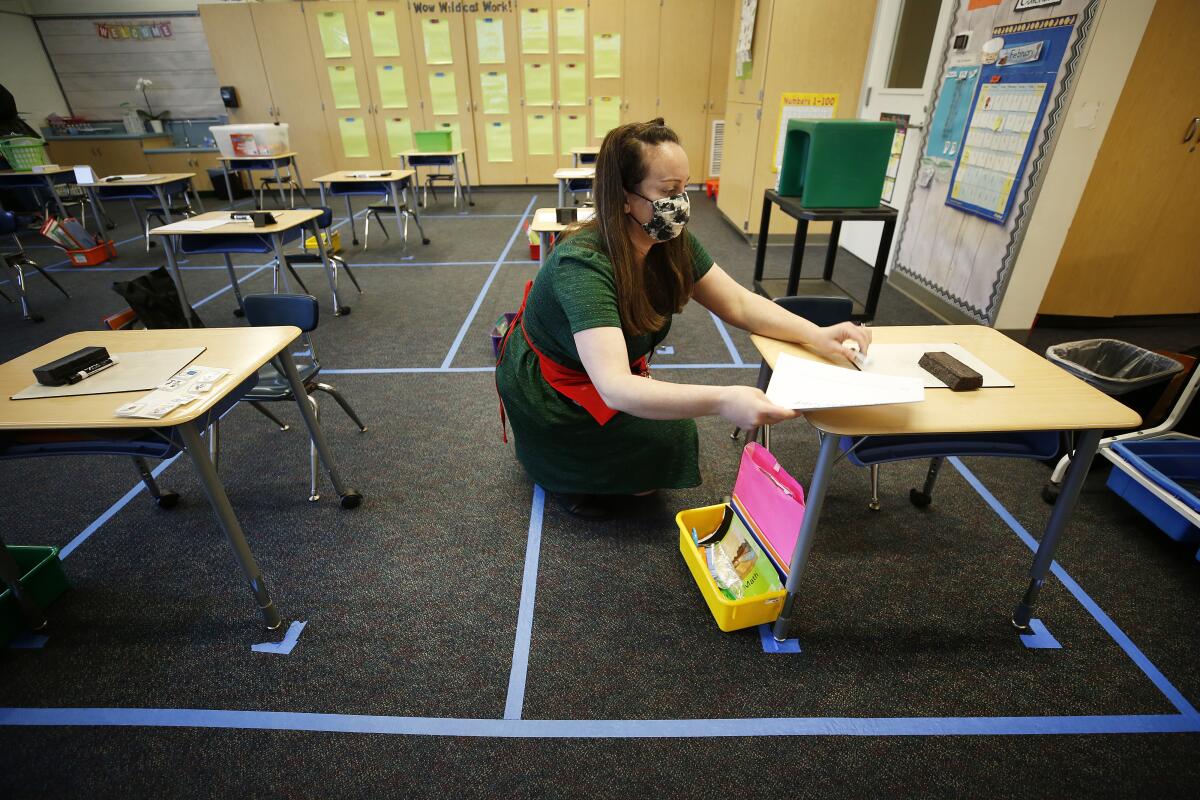

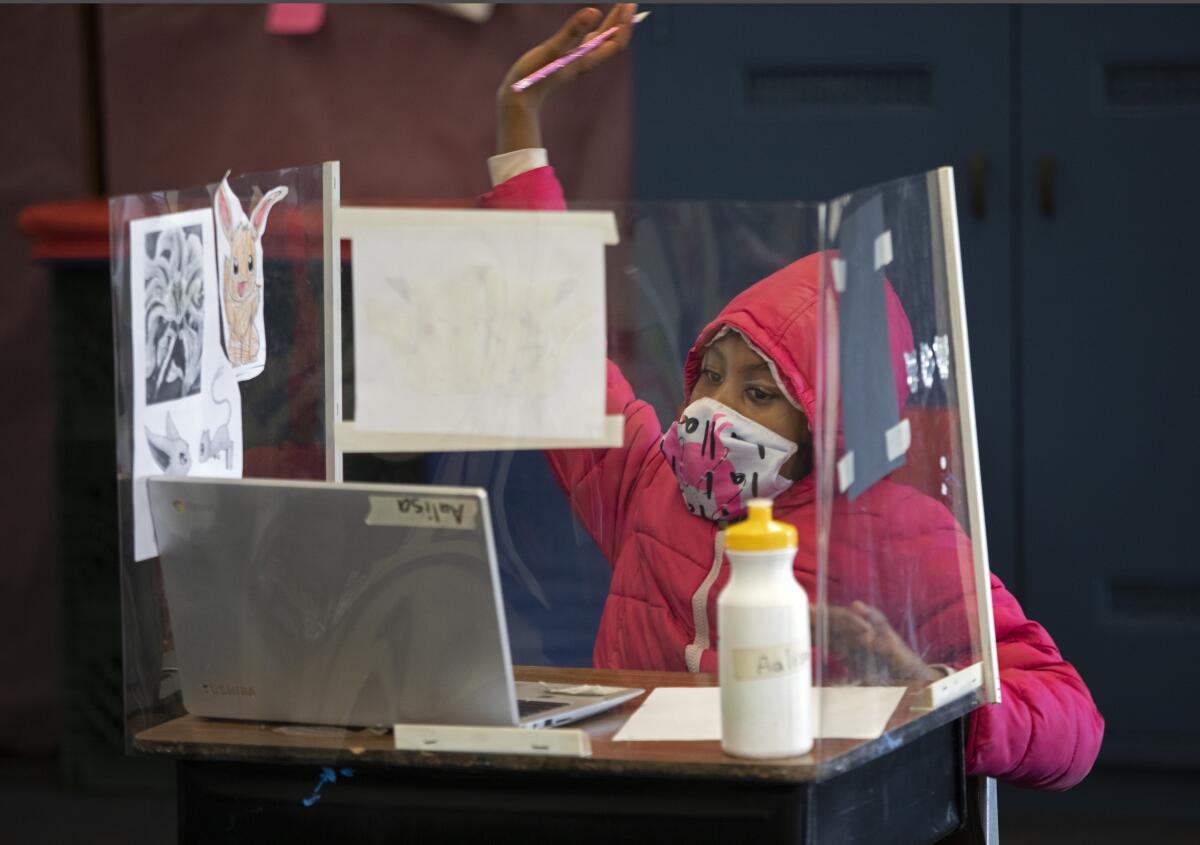

Sinnette spends her days ensuring desks are socially distanced, teachers have KN-95 masks and acrylic plastic dividers are installed.

“When I go on campus and see the in-person instruction that’s happening, it really makes you understand why you’re doing all of this,” she said. “Kids need the structure, to be in school.”

A Times survey of more than 20 school districts throughout Los Angeles County in the past two weeks has found that districts in wealthier, whiter communities such as La Cañada are more likely to be moving full steam ahead to reopen elementary schools and have plans in place to welcome students back as soon as permitted — within as little as two weeks if coronavirus infection rates continue to decline.

The Wesley School, a private academy in North Hollywood, announced it has vaccinated its teachers even though teachers are not yet eligible under current county health department rules.

They were among the first to bring back their youngest students under waivers and guidelines allowing in-person instruction for high-needs students. These districts are building on that momentum to quickly expand their reopening.

Districts serving less affluent Latino and Black communities — some of the hardest hit by the pandemic — are further behind. Their leaders spoke of the suffering and fears of their families in the darkest months of the pandemic. School officials, measuring the hardships within their communities, largely did not use waivers to bring back young students.

Their teachers and staff, too, harbor ongoing worries about the trajectory of the virus in the neighborhoods they serve. Although they want to bring students back to school, many said their reopening date was uncertain.

“It’s like making decisions in quicksand,” said Lawndale Elementary School District Supt. Betsy Hamilton, where 82% of 6,000 students come from low-income families.

Researchers at USC have found that the question of whether to reopen is divided along racial and economic lines. In a national survey conducted last month, 63% of white parents favored some form of return to in-person learning — either full or part-time — as did 68% of those with incomes over $150,000. More than half of Black, Latino and Asian parents, meanwhile, favored remote learning.

The Times contacted 23 districts throughout the expanse of the county to learn whether they had partially reopened campuses, planned to do so soon or saw in-person learning as a distant goal.

Ten districts are prepared to reopen some classrooms as soon as the county allows or plan to bring in additional grades at schools that have already partially opened under previously approved state waivers and exceptions for high-needs students.

All of those districts serve a minority of students from low-income families, according to state demographic data on their enrollment.

Thirteen said they did not yet have a date for reopening. Ten of those are in communities where a majority of students are from low-income families.

A proposal by Councilman Joe Buscaino to pursue litigation forcing L.A. Unified to reopen campuses receives cool reception from other city officials.

Among the districts serving low-income communities, there was no consensus about whether campuses should reopen when the county reached the threshold for fully reopening elementary schools — a daily infection rate of fewer than 25 cases per 100,000 people. Public health officials have said the infection rate could achieve this metric next week.

Some of those districts have brought back small numbers of students for one-on-one assessments, services for special-needs students or supervision for students who lack a suitable environment at home for remote learning. But district leaders in some of these communities also said their parents were not pushing for a fuller reopening.

Anita Chu, superintendent of Garvey School District in Rosemead, said this week she would need “a crystal ball” to predict if or when schools would reopen this year.

The district educates about 4,400 K-8 students from Rosemead, San Gabriel and Monterey Park. More than 80% of students qualify for free and reduced-price meals. About 60% are Asian/Asian American, and 40% are Latino.

In November, the district conducted a parent survey and found that only one-third of families wanted their children to return to campus. Based on that information, Chu said, the district chose not to apply for a TK-2 waiver but instead focused efforts on bringing back small groups of special-needs students.

“The No. 1 guiding principle for us is, we’re here to serve the community,” Chu said. “If our parents are ready, we will do whatever we need to reopen the schools.”

A wider reopening will depend in part on negotiations with the teachers union, which have been difficult, Chu said. Fluctuating case rates and availability of vaccines for teachers and staff, originally expected in late February, are big unknowns.

“In a few weeks,” she said, “maybe our teachers will feel so confident and will feel so much more safe, especially if they become eligible for the vaccine.”

Chu said she planned to survey parents again, though she doesn’t expect a big change in sentiment. Many students in the district live with people who are essential workers. Some have lost relatives due to COVID-19.

“We have a lot of families that have been impacted by the pandemic,” she said. “Because of that, they typically have a more heightened level of anxiety and concern about returning to school. At the same time, we have a group of Asian parents who experienced SARS in Asian countries a decade ago. They have seen and experienced that and have a higher level of anxiety.”

With the school year rapidly slipping away, the issue of vaccines for teachers is at the center of negotiations between Gov. Gavin Newsom and lawmakers.

Many district leaders in low-income communities said their neighborhoods had felt the devastating impact of COVID-19 — and that that was key to their decision-making.

Because the virus is so disproportionately affecting communities of color, focusing on reopening isn’t necessarily the solution for addressing educational inequities, said Shaun R. Harper, executive director of the USC Race and Equity Center.

“It’s an important question for sure, but in the meantime can we continue to think creatively and intentionally about how to make remote learning less inequitable for Black, Latino and lower-income communities?” Harper said. “It seems to me in recent months we’ve just given up on that. I think that’s a mistake.”

El Monte City School District has been ready to reopen for months now; its schools have all the necessary personal protective equipment, personalized desk shields in every classroom and hand-washing stations throughout its campuses.

But because local coronavirus case rates are higher than average for L.A. County, the district has opted to stay closed, save for 400 students who attend in-person learning pods. Those students are the ones who have struggled the most with distance learning, or whose parents need child care while they work, said Supt. Maribel Garcia. The district is about 80% Latino, and more than 90% are from low-income families.

“The message I continue to share is that El Monte is going to reopen when it’s right for El Monte to reopen,” Garcia said. If L.A. County elementary schools are eligible to reopen in the coming weeks, Garcia said her district would have those conversations when the time came.

“We’re constantly taking the pulse of the community and our teachers to see how they feel,” Garcia said. “It’s all about our local numbers.”

In Lawndale, officials decided in late January that schools would not reopen for the remainder of the school year. Hamilton, the superintendent, said that when she met with a group of parent leaders, only one felt comfortable sending her child back to school.

“A judgment call had to be made about how long it would take us to get to a point where this community would be comfortable with students coming back on campus,” Hamilton said. The district may, however, revisit that decision if case rates continue to fall, she said.

Meanwhile, districts in more affluent communities — such as La Cañada Flintridge, Palos Verdes Peninsula, Redondo Beach and Calabasas — have already reopened for their youngest elementary school children under previously approved waivers or the exception for high-needs students. When allowed, several are ready to open their doors more fully.

On Feb. 1, the Hermosa Beach City School District welcomed students in transitional kindergarten through second grade back to school under a waiver. As soon as the district is permitted to bring back grades three through five, it will do so, said Supt. Jason Johnson.

“We took the stance long ago that we were going to progressively reopen in alignment” with the Department of Public Health, Johnson said. “When it’s allowed, we are going to reopen.”

About 5% of the district’s students are from low-income families, and the city is among those with the lowest case rates in the county.

“We’ve taken a measured approach,” Johnson added. “I view education as an essential service. We know that our kids need it.”

On Tuesday, South Pasadena joined the list of districts prepared to reopen. Students in preschool through second grade and those in special education will be able to return for in-person learning starting Feb. 18. The board also agreed to meet in the coming days to discuss reopening third through sixth grades.

Leaders in L.A. Unified, the state’s largest school system with about 465,000 K-12 students, have been especially cautious about exposing staff, students and their families to potential health risks. Only a tiny fraction of students with special needs have received in-person services, and even those were shut down in early December. There’s no timetable for reopening. The district, where 80% of students come from low-income families, remains in negotiations with its teachers union, United Teachers Los Angeles, over what reopening would look like.

The union has made it clear that it’s not ready to endorse the return of its members or the students they teach, saying that coronavirus case rates in the communities served by the schools are too high for a safe return and that officials should focus on vaccines for educators and other staff, school safety strategies and low community transmission rates.

Supt. Austin Beutner, meanwhile, outlined what he called “three easy pieces” needed to reopen preschool and elementary classrooms for a quarter of a million district students. One of those pieces — putting health protocols in place in schools — is already complete, he said. The others are getting community spread of the virus down to acceptable levels and vaccinating about 25,000 staff members.

“While Dorothy in the ‘Wizard of Oz’ might have said tap your heels together three times and say, ‘There’s no place like home,’ and you’ll be there, actually returning to schools is not so simple,” Beutner said. “As difficult as the decision was to close schools in March, reopening is harder.”

Times staff writers Nina Agrawal, Andrew Campa and Laura Newberry contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.