Pepper spray, Instagram and buddy systems: How Asian Americans are dealing with attacks

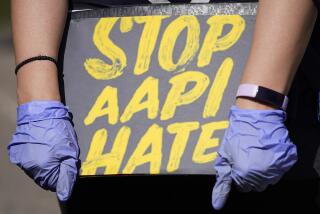

Asian Americans have been dealing with rising anxiety about racial attacks since the COVID-19 pandemic began — everything from ostracism to cruel comments and physical violence.

The shootings in Atlanta that left six Asian women dead have pushed these concerns even more to the forefront. Some say they are going out less — and when they do, they go with other people for protection. Others say they have smartphones ready to record incidents of hate.

Here are some voices from across Southern California:

Buying pepper spray in bulk

The slightly socially distanced line at Lien Hoa BBQ Deli inched forward. Customers at the takeout joint in Orange County’s Little Saigon couldn’t keep themselves from getting too close to one another as they neared the cashier to pay for fragrant roast pork and duck.

People ordered juicy, sizzling meats from a heated glass display as talk swirled around headline news, including the arrest of what some described as “the American man attacking Asian women.”

“I saw on the news that the police haven’t figured out why they have the crime. Is it because someone from a minority culture does not deserve as much protection? Or is it because they deserve to be standing targets?” said Bill Tran, a tutor from Santa Ana. “It’s ridiculous that my sister, my aunt, my grandmother, can’t experience security in their own city. No one feels like they can just run outside at any time.”

Tran asked a worker at the barbecue spot whether he felt safe in light of increasing racially motivated attacks. The man shrugged, then confided that his daughters had bought a bulk supply of pepper spray.

“Even people in the ethnic enclaves are preparing,” said Tran, 31, who is Vietnamese American. He makes sure his phone battery is always charged “in case something happens and I need to record it. Videos will be our record.”

A buddy system, ready to witness the hate

Near the entrance of Peking Kitchen along Santa Ana’s bustling 17th Street, Mary Lau and friend Lynn Porter texted family members to see whether they had any food orders.

The 20-something women say this week is a good time for comfort food, given what’s happening in Southern California and around the nation.

“We’re interested in the news about vaccines — you know, how to get them — but all we hear is about violence,” said Lau, of Anaheim, who is Taiwanese American.

She visited Porter, who lives near the restaurant, and they decided to follow their pattern of supporting small businesses during the pandemic.

She said some of her buddies worry “what would happen if these struggling stores become targets.”

Lau worries for the mental health of immigrant families “just trying to live their lives and stay safe. Many of them are doing honest work. They need public support for their right to live harassment-free.”

Lau and Porter, who is half Chinese, say that when they leave home, they are never alone — they make sure to have someone accompany them.

“In this environment, you need a buddy. Someone extra to be a witness,” Lau said, “in case something goes wrong.”

Speaking up about racism on Instagram

Kym Estrada, a 29-year-old business owner in Long Beach, took to Instagram to express her frustration about anti-Asian hate that has bubbled up in the last year.

“We ain’t a monolith,” she wrote from the San & Wolves vegan bakeshop account. “We span all different parts of an entire continent. My entire life I’ve seen my elders and peers being treated less than because of their slanted eyes and for not properly pronouncing a word correctly because English is their second or third language!? I’m telling you right now, this and future generations of Asian Americans will not allow this hate to proceed.”

It’s probably not the most strategic move to be so open about her beliefs on social media, and people send her direct messages telling her so, she said. But she doesn’t care.

She wants people to know what is happening in her community, especially white folks who make up much of the vegan community and her following.

She writes from the safety of her computer, a privilege her immigrant parents didn’t have.

When she heard the news Wednesday morning about the attacks on Asian women in Atlanta, she felt surprised that she was so affected because it was so distant from her. But the moment has caused memories of racism to bubble up and moved her to take a stand.

Estrada said she remembered people calling her Chinese as a kid and laughing, as though it were an insult, even though she is Filipina. Her parents didn’t teach her Tagalog for fear of her becoming alienated from her peers. They never gave her homemade lunches to take to school — they packed Lunchables instead, so she could be like everyone else.

When she got old enough to date, she remembers being keenly aware of the fetishization of young Asian women. She made an effort to be loud and vocal, to avoid being seen as submissive and targeted by men. She avoided dating white men.

It comes as no surprise to her, then, that investigators claimed race was not a factor in the Atlanta attacks and that the suspect claimed to have a sex addiction.

“To me, it’s quite obvious it was racially motivated,” she said.

In the last year, she experienced a rise in disturbing encounters with strangers, she said.

One time, someone pushed her off a sidewalk. On another day, a man flipped her off as he drove past her. Her partner, who is also Filipino, has been told to go back to his country several times.

Despite years of racism in her own life, this is a “lightbulb” moment, she said.

“I have always experienced some sort of anti-Asian hate in my life, but growing up I didn’t see it as hate. I saw it as people making fun of me and my parents,” she said. “I accepted that ‘Asians look funny.’ There’s a lot of unlearning to be done.”

Estrada said that until now she hadn’t thought much about her safety as a young Asian American business owner. She’s worried more for her mother, who works as a bank teller and has had racist encounters her whole life in public spaces.

Estrada said she probably won’t be talking to her parents about her fears or the violence, though.

It’s a “tricky” conversation because of differing political views between generations, she said.

A feeling of inevitability

Michelle Nguyen Bradley said she is only now learning to have conversations about race with her friends and family, despite grappling with these issues her whole life.

“The model minority myth is so bad for us because it means they think all of us are either ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ or we’re doctors,” said Nguyen Bradley, a 38-year-old Palms resident and online show host.

She choked up at the thought: “Asian Americans are taught not to take up space or talk about ourselves too much. When some of us do speak up, it feels like no one is listening.”

In the past, it has been easy to bury her head in the sand, she said, because horrifying racist attacks weren’t happening directly to her or on her block.

As she gets older, that’s harder to do, she said.

“I was scared of it happening, and it finally did happen, but just not to me. And it’s not any better,” she said.

And she knows it could happen to her.

“You’re carrying this feeling of inevitability,” she said.

Nguyen Bradley said she’s worried about her immigrant Vietnamese parents and finds it hard to broach the subject of racism in light of the Atlanta attacks.

They have mostly been staying home during the pandemic — her father is recovering from COVID-19. But she worries about the moments they have to leave their house in a mostly white Pittsburgh neighborhood.

“Of course, I’m worried if they go to Walmart or that kind of thing,” she said. “Asian kids, we don’t want our parents to worry. We see how far we can get without talking to them about it.”

As for herself, Nguyen Bradley started taking precautions early last year, considering the racist rhetoric at the start of the pandemic, but has since let go a little.

She would avoid walking her dog or getting the mail at night, asking her husband to do the tasks instead. She would clench her phone in her pocket while she was out and about, ready to call someone or take photos if she needed to.

But now, she’s exhausted.

“I can barely get out of bed,” she said. “You can’t live your life constantly on guard.”

Envisioning a future where she feels safe “is very cloudy.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.