‘Unacceptable, irresponsible’: How 17 million gallons of sewage fouled Santa Monica Bay

There is growing scrutiny over a 17-million-gallon sewage spill into the Santa Monica Bay, with many asking how the spill occurred and why it took so long to alert the public.

“What happened yesterday was unacceptable and irresponsible,” Los Angeles County Supervisor Janice Hahn said Tuesday. “We need answers from L.A. City Sanitation about what went wrong and led to this massive spill, but we also need to recognize that L.A. County Public Health did not effectively communicate with the public and could have put swimmers in danger.”

Here is a breakdown of what we know — and what we don’t.

How did 17 million gallons of sewage get dumped into Santa Monica Bay?

How did the spill occur?

Authorities are still investigating.

The emergency discharge at Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant in Playa del Rey began Sunday evening and ended around 4:30 a.m. Monday, according to interviews.

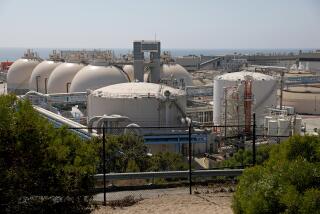

The 17 million gallons — about 6% of the facility’s daily load — amounted to the largest emergency discharge conducted at the Hyperion plant in a decade, officials said. The plant, which began operating in the 1920s, is the city’s oldest and largest wastewater treatment facility.

During the hours-long operation, crews directed the sewage through a one-mile pipe that ends 50 feet under the water, said Timeyin Dafeta, executive plant manager at the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant. The plant normally discharges wastewater 190 feet down, using a five-mile pipe.

Dafeta said an investigation was ongoing, but his crews had ruled out human error or mechanical failures.

He said construction materials, including wood chips and pieces of concrete, along with paper and grease, clogged the filtering screens. The materials were either flushed down a toilet or dumped in a maintenance hole somewhere along the city’s 6,700 miles of sewage pipes, he said.

“Those things should not be in our system,” Dafeta said. “That, in essence, is what caused the whole thing.”

He said crews tried replacing the screens and diverting water but were forced to begin discharging the sewage through the emergency pipe around 7:30 p.m. Sunday to avoid a “catastrophic situation.”

Hyperion’s executive plant manager said the facility became inundated with ‘overwhelming quantities of debris’ Sunday afternoon.

What do we know about the one-mile pipe?

The one-mile pipe was last used for a major discharge of wastewater in 2015, Dafeta said.

At that time, the plant used the one-mile pipe for an emergency during a rainstorm, officials said. But the flow also expelled trash that had been lying dormant in the pipe for years, forcing the closure of Dockweiler Beach.

Later that year, he said, the plant received authorization from the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Board to use the pipe during repairs of the five-mile pipe.

Heal the Bay’s annual report ranks the cleanest and dirtiest beaches in California. This year’s survey also graded popular rivers and lakes in Los Angeles.

What beaches were closed?

Dockweiler and El Segundo beaches, which are those closest to the plant, remain closed.

How long did it take to alert the public?

The discharge began Sunday night and ended at 4:30 a.m. Monday, officials said.

But public health officials didn’t post a beach closure advisory on the county website, urging residents to avoid swimming at Dockweiler and El Segundo beaches, or share the notification on Twitter until 5:30 p.m. Monday.

Officials and environmental experts said such delays put the public at risk, and the county needs to improve its protocols for notification and testing.

“A press release posted on the L.A. County Department of Public Health webpage is not good enough,” said Shelley Luce, president and chief executive of Heal the Bay. County officials should have begun informing the public early Monday via social media, she said, adding, “It’s time for a better protocol.”

Julio Rodriguez, a captain with the county Fire Department Lifeguard Division at Dockweiler Beach, told The Times his crews found out about the beach closure around noon — after seeing a county worker posting a sign on a lifeguard tower.

“That’s how we received official notification of the closure of the beaches,” he said.

After seeing the sign, Rodriguez said, lifeguards began warning beachgoers to stay out of the water.

Brett Morrow, a spokesman for the Department of Public Health, said late Tuesday that state officials alerted the agency about the spill at 8:11 p.m. Sunday and that health inspectors arrived at the plant at 10:36 p.m.

He said officials at the Hyperion plant confirmed around 10 a.m. Monday that 17 million gallons of untreated sewage had been discharged, and county health officials began posting signs at the beaches by 11 a.m.

Morrow said water testing was conducted Monday morning, at the discharge area and at beaches seven miles north and seven miles south of the spill.

Tuesday’s test samples were found to be within state standards for acceptable water quality, Morrow said. If state standards are met again Wednesday, the beaches will reopen Thursday.

“We are evaluating our response to this incident and will update our practices going forward to ensure that measures are in place to effectively notify the public,” Morrow said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.