Hate permit parking and pricey lots? Blame L.A. — we invented them

How about a column on parking? my editor says. Almost everyone cares about parking.

It’s right up there with air, or tacos.

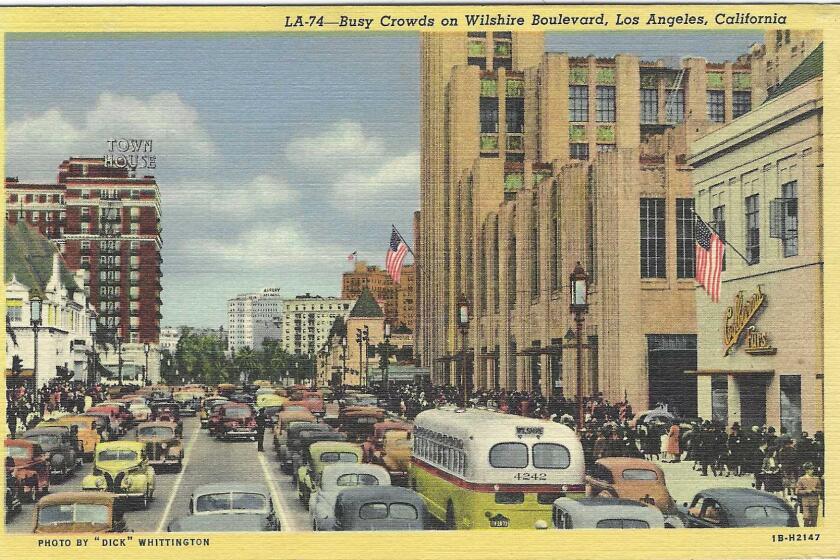

If anything vexes us almost as much as cars when they’re moving, it’s cars when they aren’t — when they are, as a 1920 L.A. Times article referred quaintly to parked cars, “standing autos.”

Parking was almost the first but a long way from the last of the un-thought-out consequences of L.A.’s auto-idolatry.

Because all of this hangs on the numbers, here are some of them:

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

- In the 10 years between 1920 and 1930, L.A. County’s car population Jiffy-popped from 161,846 to 806,264, as its human population rose from 576,000 to 1.24 million.

- In 2020, by the DMV’s reckoning, the human population stood at 10 million, and the vehicle population — motorcycles, trucks, trailers, cars — at 8.15 million. Either that’s a lot of toddlers behind the wheel, or a lot of us have more than one set of car keys in our pockets.

- Where to park all of them — one 2015 study concluded that about 200 square miles, 14%, of L.A. County’s incorporated land is devoted to parking, and yet spaces never seem to be where we need them when we need them.

A full generation before the nation’s first parking meters were being installed (in Oklahoma City, 1935, an idea begotten by a newspaperman, and yes, you may all hiss now), L.A. was already bedeviled by parking mayhem.

In April 1912, the maniacally pro-business Los Angeles Times was nonetheless incensed by the “greedy plan” of someone who undertook to charge race fans to park in vacant lots to watch a popular auto race in Santa Monica. (That initiative spirit endures in people who live near the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and turn game-day migraines into money by charging cars to park on their lawns.)

From that racecourse entrepreneur down to the present day, we have created more iterations of parking and parking limits than any rational driver can take in.

When we sanctify our cars, we do the same with the space we put them in: Permit parking, restricted parking, valet parking, handicapped parking, red curbs, yellow curbs, white curbs, green curbs, parallel parking, stacked parking, angle parking. Did I forget any?

Of course it would be Los Angeles where an eight-story, 1924 Beaux Arts parking garage is enshrined in the National Register of Historic Places. In three years we should throw it a big 100th birthday party to show the world that L.A. has its priorities right.

Fanciers of L.A. architectural history know that many in memoriam accounts of vanished, fabulous buildings — like theaters as gorgeously ornamented as Versailles — end with the tombstone phrase, “demolished to make way for a parking lot.”

Parking in Los Angeles is about luck and skill. So save time and money by learning these hacks with yellow curbs, green curbs, holiday rules, valet and more.

Oh, the things we do for parking.

The most flamboyant parking-related L.A. murder I could turn up happened almost two months after the Pearl Harbor attack. A 25-year-old woman came home from a happy hour or two at a cocktail lounge and parked at the curb in front of a “mystic temple of spirits” on Sunset Boulevard, the home and office of a psychic who regarded the younger woman as a kind of adopted daughter/protegee.

The psychic rebuked the younger woman for not parking in back as usual; the front spot was evidently reserved for clients. The younger woman — inevitably “blonde, attractive” — hauled out a .32 and the women fought over it. Amid the paraphernalia of her craft — a human skull, a crystal ball, and some incense — the psychic was killed, shot through the heart.

By 1916, 100 new cars were hitting the Southern California streets every day, and downtown L.A. was the “Hunger Games” of parking. One Times letter writer brutally demanded that the city pave over Central Park — Pershing Square — because “the grass and flowers don’t buy anything.” A Times headline sighed, “The Chances Are That War Will End Before Broadway Jam is Eliminated.” The war was World War I.

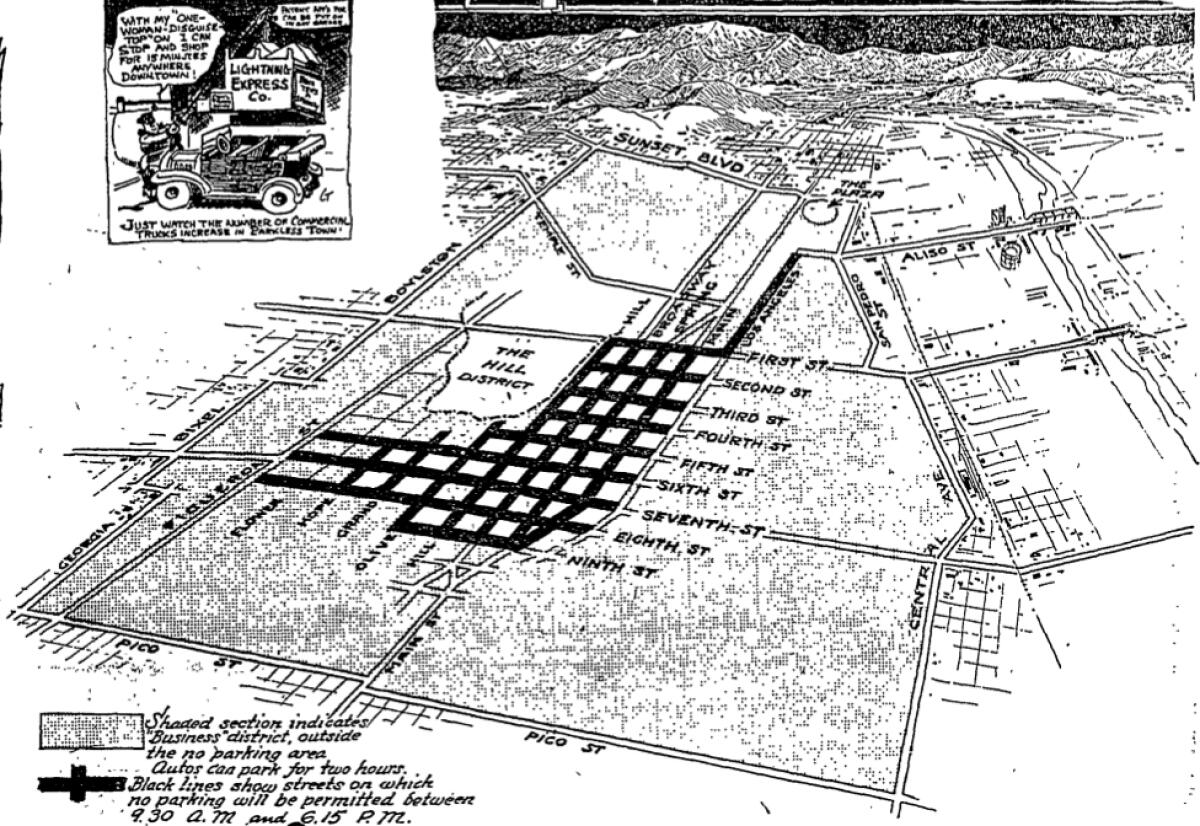

On each weekday in 1920, 30,000 cars crammed into downtown. The city decided to solve this sclerosis by banning all street parking in central downtown. The law didn’t just have teeth; it had fangs. Overstay by one second the two-minute curbside limit, and traffic cops were empowered “to arrest and take to the police station all persons who violate the new law.”

The law also prohibited taxi stands for idling cabs, as well as random curbside cab-hailing. If you ever wondered why it was impossible to simply flag down a taxi on downtown streets the way New Yorkers do, look no further. “The convenience of being able to pick up a taxicab at the theater entrance after the show on a rainy night,” mourned The Times, “will soon be a thing of the past.” If you wanted a cab, you’d have to telephone for one — if you could find a phone.

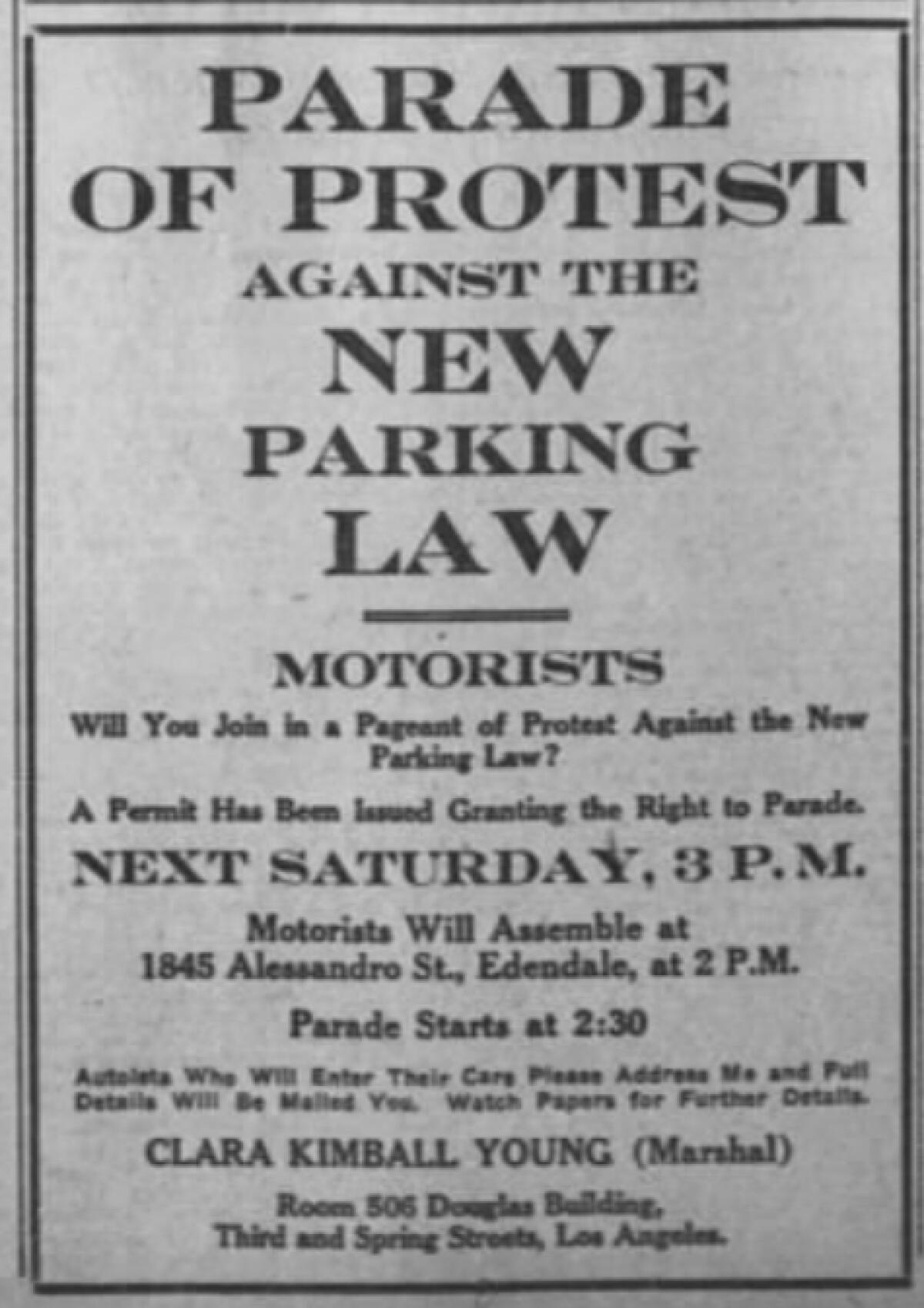

It took about 90 years for the city to walk back that taxi-hailing ban, but it took only a few weeks for the City Council to renounce its ruthless 1920 parking shutout.

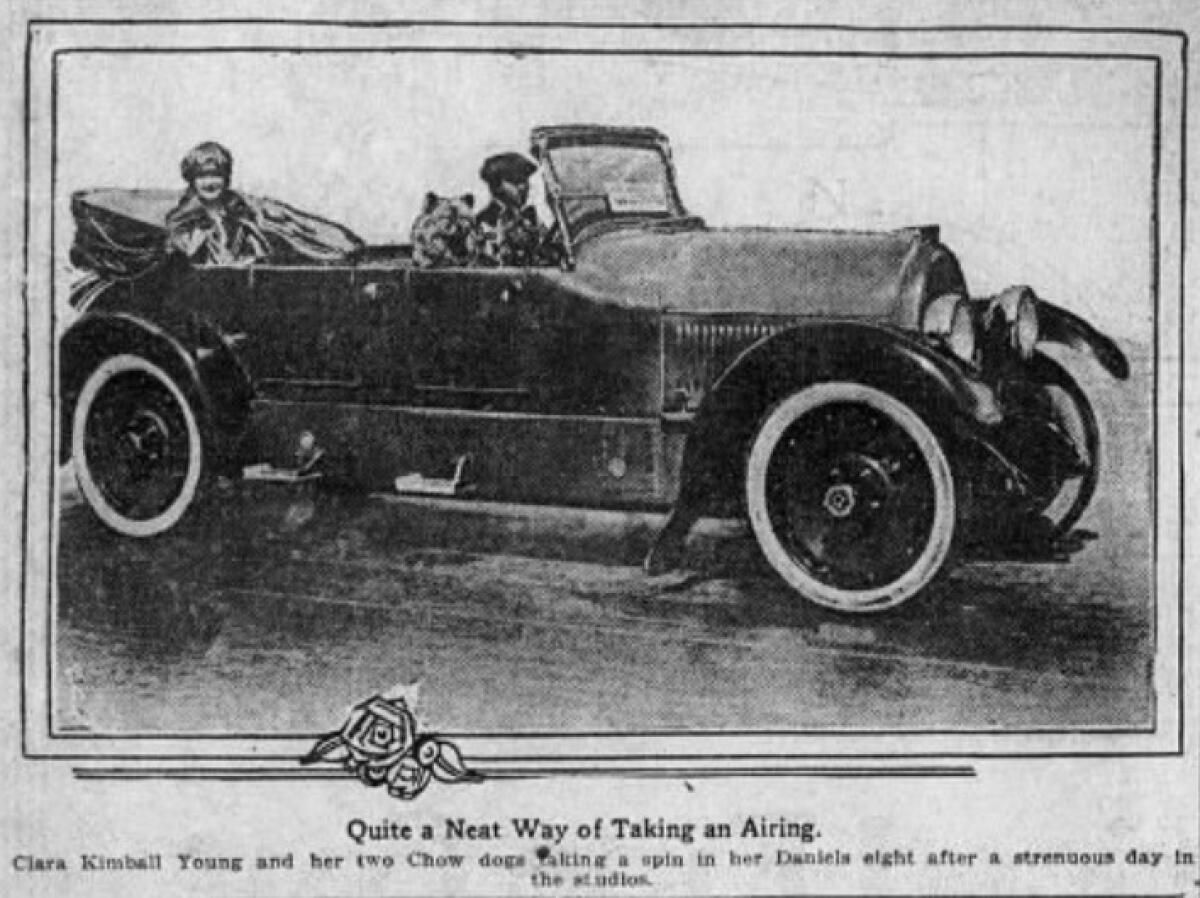

Downtown merchants and suburban women — the former losing customers, the latter protesting that it was too hard to be customers — joined forces and staged an enormous slow-mo, drive-by protest along downtown streets. Hundreds of cars adorned with placards and banners were led by Clara Kimball Young, a grande dame of silent movies, who drove downtown from her Edendale studio to lead the parade, probably in her brand-new custom Daniels 8 limousine.

(Hal Roach and Will Rogers turned this civic crisis into a short movie in 1924, “Don’t Park There!”, a trifling story of a man who can’t run an errand because he can’t find a place to park his buggy.)

“Everybody dissatisfied,” The Times concluded feebly. True then, true now. And true of readers, who may or may not find their personal griefs and beefs addressed here. So which is yours?

- On a single block, an apparently contradictory welter of street signs can take longer to read than this column: no parking between these hours, no overnight parking, no parking during street-sweeping, permit parking only. You can read them all closely and still mess up.

- The city of L.A. suspended a lot of parking ticketing during the COVID-19 pandemic, when people were home from work or even out of work, but started ticketing again last year. Who gets these tickets, and where? A few years ago, the local NBC TV station found that almost 20% of L.A. city parking tickets are left under windshields in only about 500 of the city’s 360,000 blocks, and that more than 123,000 vehicles carry at least five parking tickets. The scofflaw champ might be the Toyota that KNBC Channel 4 found with 69 unpaid tickets over nine months for illegal parking on the same street in Panorama City. Another man, owner of a fleet of delivery trucks, just throws parking tickets away. His drivers park in red zones and in front of fire hydrants, “They are breaking the law,” he said, “but there’s no other way for them to do their job.” However: many homeless people living in their cars or RVs collect fistfuls of tickets too, tickets that could lose them their vehicles if they go unpaid.

- In any city in L.A. County, and in many neighborhoods in the city of L.A., you may see posted parking limits peculiar to that neighborhood. Santa Monica, Burbank, Glendale have permit parking restrictions. West Hollywood has so many that they amount to a kind of alternate language. Permit parking is what neighborhoods may request when street parking for businesses squeezes out residents. Former council member and county supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who came up with the permit parking idea more than 40 years ago, has grappled with the countervailing demands of wanting a carless future and living with a car present. “Cities throughout our region have required developers to provide parking for their customers or residents. Eliminating such requirements in order to reduce development costs may be a good idea in theory, but it has consequences. Car owners will be circling neighborhoods to find curbside parking, and there simply aren’t enough curbs to accommodate them. Some retail shops that rely on curb parking for their customers will lose business because local residents will be taking up curb space. Government should be careful before eliminating all parking requirements, because if it turns out to be a mistake, it can’t be corrected.” One-size-fits-all doesn’t suit every street or every neighborhood.

- How ‘bout that arrogant “I’ll just be a minute” exceptionalism of people who illegally park in red zones or on major streets during rush hour, when a single lawlessly parked car can make hundreds of people late for work? For a while, L.A. was assigning “tiger team” strike forces to ticket and tow these rush-hour scofflaws immediately; do you still do that, L.A. transportation department? If not, please start them up again.

- When all else fails, you may have to fork over the money for parking lots and garages. It comes down to what irks you more: spending money to park, or spending time to hoof it from a faraway parking place to the place you want to be, and then sweating and fretting over the meter running out of paid time before you run back to it?

- Some people will cheat every system, including handicapped parking. Drivers forge handicapped parking placards, or illegally use a disabled relative’s parking placard. Agreed that not all disabilities are visible, yet the moral void of — to put it crudely — screwing over people with disabilities is still shocking. Steve Jobs didn’t want an elitist reserved parking spot at Apple, but regarded himself as entitled to park in handicapped spots (this was before his cancer diagnosis). In 1999, a bunch of UCLA football players would have been booted off the team if they’d really suffered from all the ailments they forged on handicapped parking applications. They pleaded no contest to getting their permits illegally, and as they left the jail, they had to run a gantlet of angry people in wheelchairs.

- Beach parking is forever spoiling for a fight. In his 1966 work, “The Pump House Gang,” Tom Wolfe described a La Jolla surf gang that made that beach its own, painting red curbs white so they could park there. Fifty-plus years later, someone else in La Jolla was doing the reverse: painting plain curbs red to keep away beachgoers. The same thing has happened up the coast around Malibu, where the owners of bazillion-dollar beach houses created bogus red-painted curbs, bogus “no-parking” and “private property” signs, even completely fake garage doors, to keep the hoi polloi (that’s us) away from legally parking at public beaches.

- The two most beautiful words on an invitation are not “no gifts” — they are “valet parking.” Valet parking was a standby Johnny Carson poke at the rich, but then it trickled down to hospitals, amusement parks, the Beverly Hills post office and ordinary businesses. Valet parkers are a Damon Runyon cast in our cutthroat parking sagas. Herb Citrin was valet parking’s founding czar, ferrying LaSalles and Packards outside the Swing Club in Hollywood before World War II, and finally landing a parking concession for Lawry’s on Restaurant Row. Unless your car is a showy Ferrari or Bentley that gets the showoff space in front, expect a wait as the valet runs off to fetch it. For a few years, I drove to so many valeted political events that the valets began to call me by name. And yes, it is irksome to be looking for a parking spot and think you’ve spotted one, only to find the meter is bagged up and marked “valet only” for some restaurant. Is this legal? Sometimes, if the company jumps through all these hoops.

- Home sweet parking space: The crisis of 1920s and ’30s downtown parking was speedily replicated in L.A.’s centrifugal neighborhoods. “Many apartment-house districts are now inadequate to contain all the cars whose owners wish to park there.” That was The Times in 1920. Not until the 1930s did cities here begin requiring that new apartments provide parking spaces, and now those aren’t adequate to two- or three-car households. In consequence, residents may spend the shank of the evening cruising the neighborhood for a parking spot, getting more brazen or desperate, and likelier to get a parking ticket. As for our cherished R-1 neighborhoods, while cities can require that new homes be built with garages, they can’t require that residents park there. So garages are turned into media rooms, storage spaces, gyms — and now, with the blessing of a state in dire need of more housing, studio apartments, “accessory dwellings.” This new law found Saratoga’s then-mayor Manny Cappello worrying that banning cities from requiring more parking to accommodate new and newly garage-less residents would certainly create more housing, but not more curb space for houses with two, three, even four more vehicles now needing street parking.

Where will this all end? Maybe only when the time we have to spend looking for parking, or the price we pay for it, finally defeats the point of driving somewhere in the first place.

Angelenos can be spotted a mile away in other locales, waiting for the walk sign while locals jaywalk with abandon. What’s that about? And what happens when people do jaywalk here?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.