San Diego scientists work on a vaccine against all coronaviruses. Yes, all of them

SARS. MERS. COVID-19. Coronaviruses caused all three diseases, and scientists are betting other members of this viral family will cause new outbreaks.

But what if a single vaccine worked against all coronaviruses — past, present and future?

Researchers from San Diego to Boston are racing to turn that possibility into a reality, and they just got some major help. La Jolla Institute for Immunology announced Thursday that Erica Ollmann Saphire, president of the organization, won a three-year, $2.6-million grant from the National Institutes of Health to develop a so-called pan-coronavirus vaccine.

“It’s a class of viruses that we know can cause global pandemics. And it’s something that we need to be prepared for,” Saphire said. “We’re trying to ward off the next pandemic.”

She’s part of a larger effort led by Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and joined by researchers at MIT, Massachusetts General Hospital and Boston University. Scientists in Boston are studying people who’ve been vaccinated or recovered from COVID-19, searching for immune responses with the potential to fight off a broad swath of coronaviruses.

Booster shots for eligible residents are expected to be widely available starting Saturday.

For this strategy to work, researchers must identify parts of the viral surface that don’t change from one coronavirus to the next and train the immune system to go after these shared regions.

Saphire’s team will handle the design of the vaccine itself. Her group has figured out how to manufacture a version of the coronavirus’ spike protein — the protein that latches onto your cells and lets the virus slip inside them — that closely mimics the shape of the spike on the actual virus.

That’s key because, for proteins, shape is everything. The millions of proteins in each of your cells fold into intricate 3-D structures, a bit like works of origami. Those shapes control what each protein does, and even slight changes affect how or if they work.

“If the protein is better structured, better folded and more stable, it will remain longer and stimulate the immune system longer,” Saphire said.

The full grant lasts five years, with additional funding to arrive in year four. By that time, Saphire hopes to have a clearer sense of how a pan-coronavirus vaccine should be administered. That means knowing how many doses people need, how far apart shots should be spaced and whether the vaccine should use proteins, RNA (like Pfizer’s and Moderna’s shots) or some other approach to spark immunity.

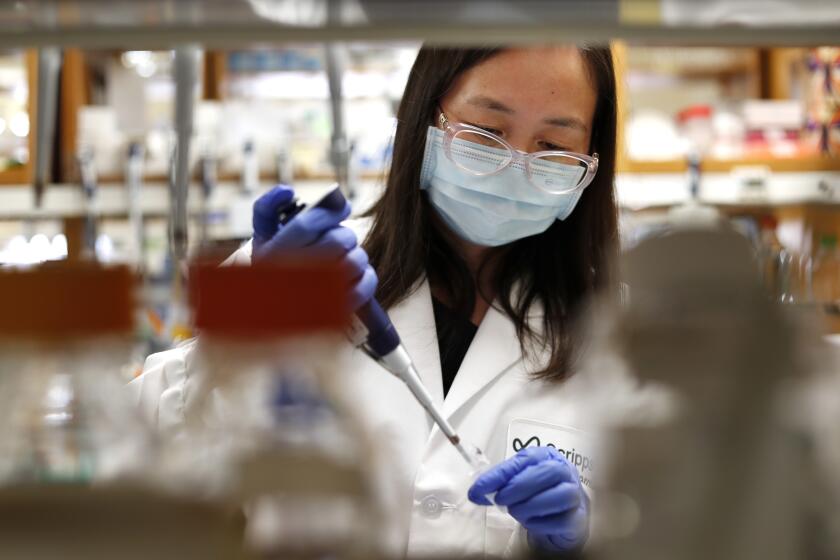

Plenty of other researchers are chasing the same goal. A 10-minute drive from Saphire’s lab, scientists at Scripps Research also are working toward a pan-coronavirus vaccine in partnership with the Gates Foundation. Immunologist Dennis Burton is one of them, and he’s employing the same strategy his team has used to study HIV for decades, closely examining antibody responses for clues on how to reverse-engineer a vaccine that could spark broad and long-lasting protection.

Researchers plan to use a series of shots to teach people’s immune systems to produce powerful antibody responses against the virus. But while the strategy is raising hopes and is built on years of research, there’s no guarantee it succeeds.

Burton thinks a vaccine that truly works against all coronaviruses will be a tall order, and Saphire agrees.

But he says that a vaccine against the viruses responsible for SARS and COVID-19 is more doable given that researchers have already found some antibodies in people that latch onto the viruses behind both diseases. There’s also evidence that previous exposure to the four seasonal coronaviruses that can cause the common cold helps against COVID-19, suggesting that a vaccine against these viruses and the novel coronavirus is also possible.

“How feasible it is depends on how broad you’re trying to make your vaccine, how many viruses you’re trying to do,” Burton said. “It’s a case of seeing how far you can push the envelope.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.