They begged social workers to save 8-year-old Sophia Mason. She was found dead in a bathtub

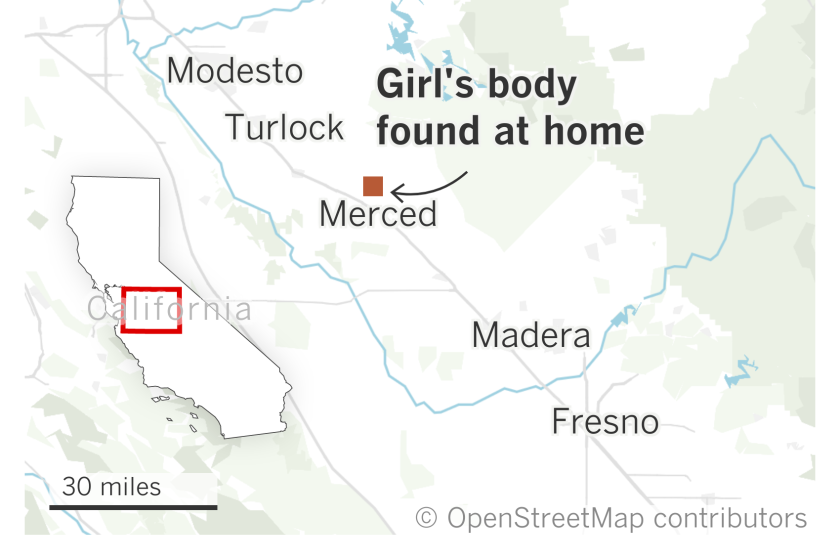

Before 8-year-old Sophia Mason’s body was found curled inside a bathtub in a Merced home, the young girl’s extended family tried desperately to raise the alarm.

For more than a year, Sophia’s aunt, grandmother, teachers and doctors reported signs the girl was being abused and neglected, at times pleading with social workers to remove her from her mother’s care.

There had been bruises and scabs and what looked like cigarette burns on her body. All were reported to child welfare workers, according to a legal claim filed against the county.

Then there was Sophia’s own account: She said her mother and her mom’s boyfriend hit her with a belt buckle, according to her aunt, Emerald Johnson, who overheard Sophia speaking with child welfare caseworkers. She said the young girl told social workers that her mom choked her and covered her mouth to quiet her screams.

Child Protective Services also investigated an allegation that her mother’s boyfriend had sexually abused Sophia, according to a police interview with the girl’s mother, Samantha Johnson. Johnson’s boyfriend denied the allegation, she told detectives, adding that she didn’t believe Sophia when she told her the man had put his penis in her mouth.

Relatives say their repeated cries for help went unanswered.

Police served a search warrant while assisting Hayward authorities with missing child Sophia Mason. It was not clear whether the body is Sophia’s.

“Everything that I told them could happen did happen,” Emerald Johnson, 33, said in an interview with The Times, adding that she had made multiple calls to the Alameda County Social Services Agency that resulted in no action. “I think they didn’t care.”

Sophia, who was last seen by extended family in December, was found dead March 11. A missing persons report filed by the girl’s aunt and grandmother a month earlier eventually led police to the Merced home her mother shared with her boyfriend. While searching the house, officers kicked open a locked bathroom door. Inside, an exhaust fan whirred and dead flies littered the floor. Sticks of incense could not mask the smell of the child’s decomposing body.

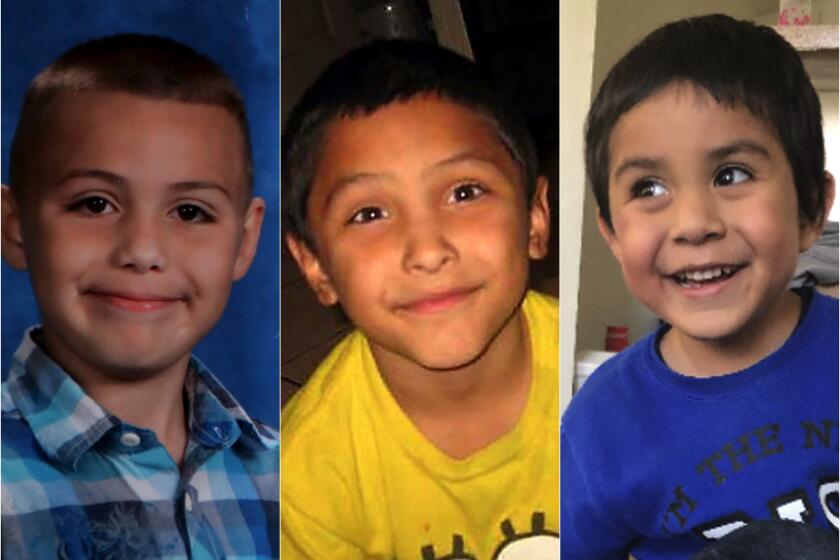

Samantha Johnson, 30, and her boyfriend, Dhante Jackson, 34, have been arrested on suspicion of abusing and killing Sophia. The two are charged with felony counts of willful harm or injury to a child and first-degree murder.

Police also have arrested three women — Daberka Johnson, 40, of San Jose; Laronna Larkins, 42, of Merced; and Myra Gutierrez, 33, of Newark — who authorities say helped Jackson evade police for months before he was taken into custody in September.

The case has sent shockwaves through the San Francisco Bay Area and sparked calls for reforms in Child Protective Services. Sophia’s fate mirrors a string of cases in Los Angeles County in which children were killed despite repeated warnings to social workers that they were in jeopardy.

The arrests, Emerald Johnson said, have brought some reassurance that justice will be served in Sophia’s death, but she and other relatives believe social workers ignored their warnings and failed the girl. In a legal claim filed against the county, the family alleges that caseworkers “knew or should have known that this abuse and severe neglect was ongoing, yet they failed to take the necessary action to protect the minor’s safety.”

It’s still unclear how Sophia died, but her mother told police after the girl’s body was found that the last time she saw her daughter was in mid-February.

After being told to sleep in a backyard shed as punishment for urinating on the floor, Sophia was allowed back in the house, her mother told police, adding that when the child came inside, she was covered in feces.

Jackson was enraged by the mess, Samantha Johnson told detectives. She described how he hoisted the girl off the floor by her hair and threw her into the hallway. She said Sophia was missing “several patches of hair” when she took her into the bathroom to wash.

Johnson told police she left Sophia in the bathroom and went upstairs. Minutes later, she heard a “thud” and went to check on her daughter. She called, “Sophia, Sophia!” at the bathroom door, but got no response, according to the Merced police report. The door was locked, and Johnson told detectives she didn’t check on her because she thought Sophia “was in one of her moods.”

The next morning, when she couldn’t find the girl, Johnson told investigators she believed her daughter had run away. Jackson told her Sophia “does not want to be your daughter anymore,” so she didn’t immediately look for the girl.

What happened after that remains unclear. Johnson told detectives she looked for Sophia for about two weeks, then traveled to Newark, Calif., with Jackson on Feb. 22. During that time, she told detectives, she didn’t contact law enforcement or report Sophia missing, adding that “her mind was in the place where she thought that [Sophia] had run away,” according to the police report.

She didn’t contact police, she said, because she feared Jackson would retaliate.

A disproportionate number of Black children are removed from their homes in L.A. County. Now, the county has backed a “blind removal” pilot for study.

Family members said this was exactly the type of abuse they and others tried to warn authorities about.

According to the legal claim filed Sept. 8 against Alameda County, Sophia’s extended family and others who knew the child made at least seven emergency child welfare calls in 14 months, but officials investigated only two. The claim — a precursor to a wrongful death lawsuit — also alleges that despite a requirement that law enforcement be alerted about allegations of abuse within 36 hours of their being reported, one of the incidents was flagged to police two months later.

“The family felt that they were pleading for Sophia’s life,” attorney Carly Sanchez said in the claim.

Emerald Johnson said she made more than 10 calls to the county’s hotline, but some appear to have not been documented. Once a caseworker was assigned to Sophia, Johnson said she started calling that person.

“I felt hopeless,” the girl’s aunt said. “Nobody was helping me. Nobody was following up.”

An investigation by the Mercury News found that social workers made glaring errors in their inquiries into Sophia’s care and failed to notify law enforcement when police should have been involved. Family members said multiple calls were ignored. When caseworkers responded, the newspaper reported, they sometimes made significant errors that could have affected the assessment of Sophia’s life at home, including one notation that Sophia’s mother had no history of drug or alcohol abuse even though she was residing at a sober living home at the time.

Some of the reports reviewed by the newspaper show caseworkers determined that in-person visits were not needed to assess Sophia’s safety. In other instances, social workers decided that Sophia didn’t face threats or risk of abuse, although their paperwork contained no notes or details about their inquiries. As part of their legal claim, the girl’s family is requesting access to those records.

Since Sophia’s death, officials at Alameda County’s Children and Family Services agency have not commented publicly about her case or the documents reviewed by the Mercury News. Michelle Love, who heads the agency, declined to be interviewed for the newspaper’s investigation.

Love also did not respond to multiple requests for comment by The Times. Alameda County officials did not respond to questions about Sophia’s case or the claim filed by her family.

Attorneys for Samantha Johnson and Jackson, who have both pleaded not guilty, did not respond to requests for comment.

L.A. County social workers and LAPD officers were told repeatedly that Liliana Carrillo was a danger to her kids. Now the children’s father is suing.

Sophia’s family says problems with the mother’s care for her daughter date back to the child’s birth. Samantha Johnson showed little interest in parenting, and Sophia began living with her grandmother in Hayward, Emerald Johnson told The Times.

It was after Sophia’s mother started seeing Jackson that relatives began to get more concerned. She became more violent with the girl during visits, her sister said.

When Samantha Johnson insisted on taking her young daughter to meet her boyfriend, the family refused to let Sophia go. There were longstanding concerns, Emerald Johnson said, that her sister was involved in prostitution and fears that her boyfriends could be pimps.

But Samantha Johnson sneaked out one night with Sophia. The next day, Emerald Johnson said, Sophia told her and her grandmother that she had seen her mother and Jackson having sex and that Jackson stared at her the entire time.

Her mother denied the allegation, but it worried relatives so much that Emerald Johnson began keeping Sophia at her home some of the time.

“From there, things just got ugly,” she said.

An Associated Press review has identified a number of concerns about the technology, including questions about its reliability and its potential to harden racial disparities in the child welfare system.

In January 2021, Samantha Johnson called police to her mother’s home and took Sophia away. Although the girl had lived most of her life under her grandmother’s care, there had never been a formal custody order. When her mother called police, they said she could take her daughter with her, Emerald Johnson said.

She and her mother quickly reached out to the county’s social services agency, warning that Sophia was not safe.

“I was letting them know Sophia is in danger,” Johnson said. “[Her mother] won’t feed her, won’t bathe her, won’t clothe her and will hit her,” she said she told the agency.

Those worries seemed to be confirmed when family saw Sophia a month later. Relatives met with mother and child at a park, along with a police officer and a social worker, to talk about Sophia’s living arrangements.

Sophia looked thinner, her hair was matted and her clothes were dirty, her aunt said. After a social worker separated the girl from her mother to talk to her, her aunt said she overheard Sophia describe how her mother and her boyfriend were beating her. Her mother denied the allegation, Johnson said.

Sophia showed bruises and scabs on her leg, according to her aunt, and also told the social worker her mother would “make me say things that are not true.”

Still, officials let Sophia leave with her mother.

Social workers would continue to be notified during the remainder of the year that Sophia was being abused, according to the claim filed against the county.

In one referral, Sophia’s mother is accused of striking and choking the child and trying to muffle her screams. Officials found bruises on Sophia’s arms, thighs and torso, and learned the girl had not been at school in weeks. She told caseworkers her mother’s friends hit her.

In another referral, social workers were told Sophia had been exposed to her mother’s prostitution. Johnson said she contacted caseworkers at least once after she found an online ad soliciting prostitution that appeared to be posted by her sister.

Although reports were taken, neither call prompted any significant action from social workers, Johnson said.

In June 2021, the claim states there was a report of a massive bruise on Sophia’s arm, from her elbow to her wrist, that officials failed to investigate. Three months later, another referral was made after Sophia was found with more bruises during a doctor’s visit and marks that looked like old cigarette burns.

“Despite this report, the county social worker who investigated the referral stated that Sophia did not have any marks or bruises indicative of abuse or neglect and closed the referral in just seven days after a cursory ‘investigation,’ ” the claim states.

Anthony, Noah, Gabriel and beyond: How to fix L.A. County DCFS

Emerald Johnson said she and Sophia’s grandmother began to worry the child might be facing more abuse after multiple calls to social workers. When family members asked Sophia how she was doing, her mother appeared angry if the girl said she was unhappy, they said. During at least one phone conversation, Johnson said that her sister hung up the phone, then had Sophia call back and say she was “good.”

She also recalled one visit when she asked Sophia about bruises on her arm. “She said, ‘Don’t ask me; Mommy gets mad.’ ”

It wouldn’t be until late February that family members realized something was more seriously amiss, Johnson said. For days, her sister called their mother, but when asked about Sophia, she would refuse to put the girl on the phone, saying she was asleep.

When her mother insisted on talking to Sophia, Johnson said her sister tried to change her voice and pretended to be Sophia. When confronted, the girl’s mother said she “couldn’t handle her and I just gave her away,” Johnson said.

The family hoped the comment meant that social services had finally removed Sophia from her care.

But on a subsequent call to her mother, Samantha Johnson seemed cheery and said she planned to visit soon, but without Sophia.

She sounded unbothered by Sophia’s absence, and Emerald Johnson said that rang alarm bells.

“I had a bad feeling that something had happened,” she said.

The next day, she filed a missing persons report — but officials think Sophia was already dead by then.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.