A 4.0 student beat all the odds. But he can’t afford a UC campus

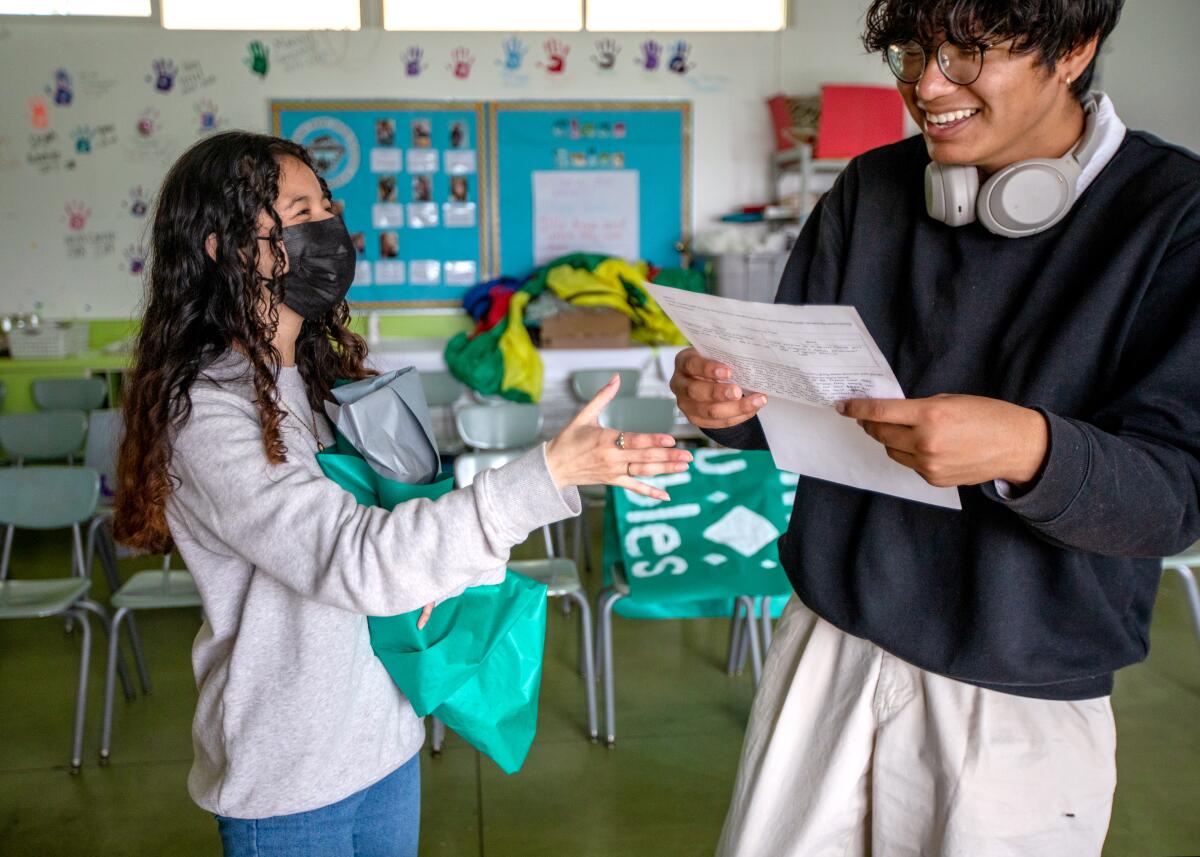

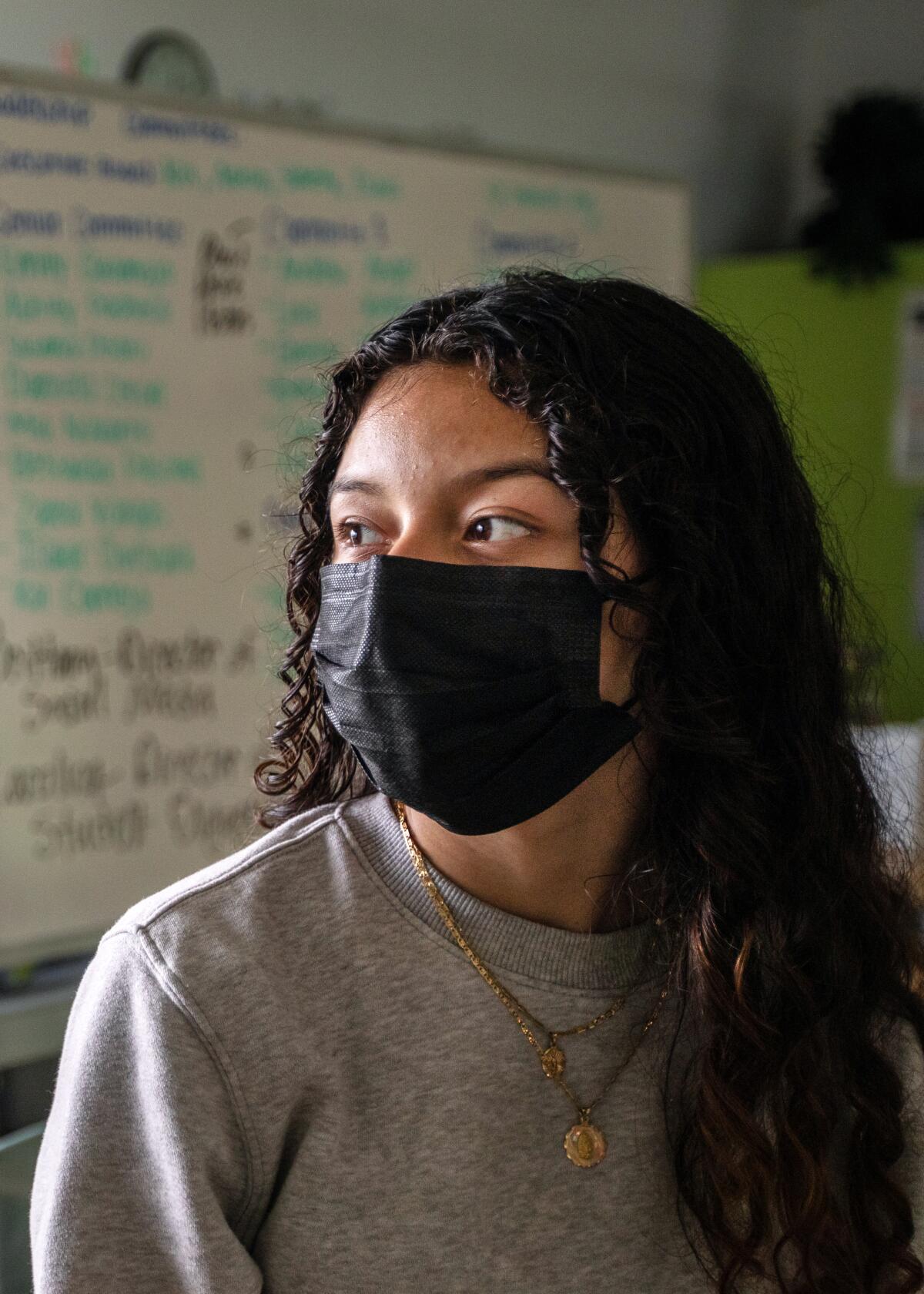

The journey to college has tested the resolve of Jonathan Cornejo, a senior at West Adams Preparatory High School in central Los Angeles. The son of a single immigrant mother from El Salvador, he had no home Wi-Fi or working laptop for stretches at a time or a study space in the family’s cramped apartment.

He sometimes felt lost in his college preparatory classes and couldn’t always find the help he needed. Yet Jonathan overcame those challenges to earn a 4.0 GPA while serving as student body president and yearbook editor in chief. His perseverance paid off last month when he received a coveted admission offer from his dream school, top-rated UC San Diego.

But Jonathan is planning to go to a community college. Even with a substantial financial aid offer, he can’t afford to attend the University of California — and he’s not alone.

His plight is mirrored across the UC system, as rising college costs compounded by inflation and pandemic fallout put dream campuses out of reach for many students. More than 10,000 of the state’s lowest-income students admitted to UC are choosing instead to attend California community colleges or California State University, in part due to financial shortfalls. At UC, the share of undergraduates who receive Pell Grants — federal aid for the neediest students — has dropped over the last decade.

Jonathan’s financial aid package left a $4,000 funding gap he says he can’t fill with income from his part-time job as a Starbucks barista or his mother’s two low-wage jobs as a cook. He and his mother are fearful about the financial burdens of taking out a loan. He’s hoping he erred in filling out his application for federal financial aid and will get more support once he amends it.

“I cried about it, I will not lie,” Jonathan said about his financial aid shortfall. “You did all these things, tried your best. Then you look at the money aspect and see you can’t afford it.”

Rising financial challenges like Jonathan’s are deepening concerns throughout UC that some of the state’s poorest students may be missing out on the system’s top-notch education, which could propel them to the highest echelons of wage earners and fuel the future state economy. UC delivers the highest completion rates and post-graduate earnings among California’s three public higher-education systems.

“We are very concerned about these trends, because the university’s mission is very tightly connected to upward mobility and enabling everyone to come to the University of California, especially low-income, first-generation and minority students,” said UC Provost Katherine Newman. “This is something we pretty much talk about every day.”

The share of UC students with incomes low enough to receive Pell Grants dropped to 33% in fall 2022 compared with 42% in fall 2012, according to systemwide data.

Nationally, rising incomes are pushing more students out of eligibility for Pell Grants even if they still can’t fully afford college in high-cost states like California. The cost of living in Los Angeles, for instance, is 40% higher than in Houston. But the Pell program makes no geographical adjustments. Most Pell recipients have family incomes under $50,000.

Among the lowest-income students admitted to UC, the number who selected CSU instead doubled to 6,946 in fall 2021 from 2015 and also doubled for community colleges, to 3,063 students, the data show. Overall, the share of first-year students with annual family incomes of less than $50,000 who enrolled at UC dropped to 39.7% in 2021 from 54.4% in 2015. Similar downward trends are evident among students who are the first in their families to attend college.

UC data do not identify the specific reason students are opting for CSU and community colleges. Marisol Cuellar Mejia, a Public Policy Institute of California research fellow, said some may not be able to afford it and some may have been denied admission to their top UC choices and want to try again through the transfer route.

In addition, UC data show far more low-income students choose community college than those with higher family incomes. Community colleges remain a cost-effective option for students who are disciplined in their studies — and UC is creating new pathways to widen transfer accessibility.

Financial aid shortfalls

Newman said several “hefty headwinds” are driving down the number of low-income students at universities across the country. In California, the key barrier to college affordability is the rising cost of housing, which financial aid usually does not fully cover — unlike tuition, which is paid by the state’s generous Cal Grant program for lower-income state students.

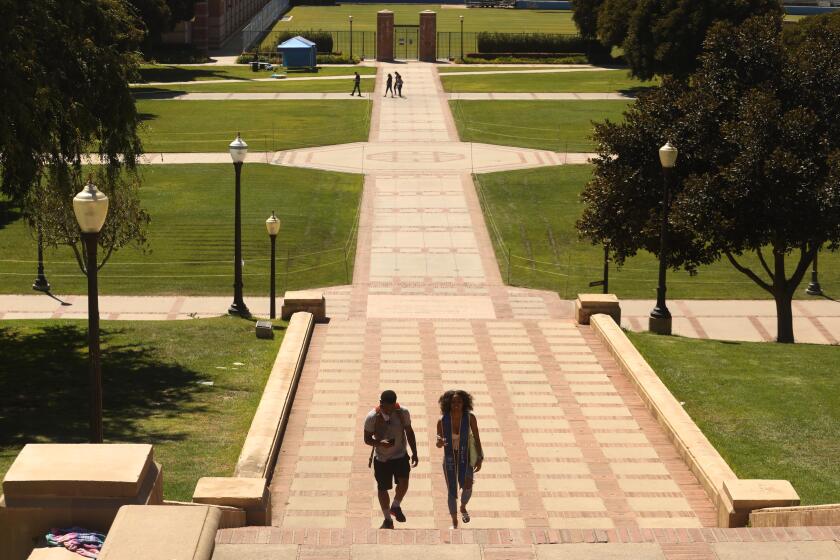

The UC system’s nine undergraduate campuses are located in some of the nation’s priciest real estate markets; off-campus living costs climbed by an average 54% systemwide between 2014-15 and 2022-23, with higher increases at UC Berkeley, UCLA, UC Irvine and UC Santa Cruz, according to UC data.

The University of California has unveiled a first-ever systemwide admission guarantee for all qualified transfer students but access to specific campuses is not assured.

But commuting is not often an option since UC campuses are farther from home for many students than the 23 CSU and 115 California Community College campuses. Many low-income students, such as Jonathan, don’t have cars.

Litigation blocking student housing projects, a potential delay in state funding and escalating construction costs are among the challenges.

“For students who are first-generation and low-income, being able to shelter in their parents’ home helps to cut the costs, and that tends to tie them to local areas, more than more affluent students who can pick up and move into dormitory housing,” Newman said.

In recent years, the state’s strong labor market has probably pulled some low-income students admitted to UC into jobs instead, Newman said. And more students may be hesitant to leave home because the pandemic fallout has increased their family responsibilities or made them wary about rooming with strangers.

Emily Gramajo, a senior at West Adams Preparatory High, has a waitlist offer from UC Riverside and acceptances from Cal State campuses at Northridge and Dominguez Hills. But even if she gets off the Riverside waitlist, she’s already decided to attend L.A. City College because the first two years would be free under the California College Promise Grant program. She said she is needed at home to clean, cook, take out the dog and baby-sit for her neighbors. She also said she would feel safer at home, having heard about “scary” dorm experiences.

She said she’s “a little sad” about missing a four-year university experience out of high school. “But I feel like it would benefit me better if I go to community college first because I could save up all of my money and I could transfer in my last two years to a university,” Emily said.

Counselors at several L.A. Unified high schools have noted the trend of UC-eligible students turning down admission offers with dismay. At Banning High School in Wilmington, counselor Araceli Fernandez said she pushes her students to choose a four-year university because she’s seen too many students “lose focus” and take three or four years to complete a two-year community college program — or end up failing to transfer.

Many parents, who may not have attended college and are struggling economically, see UC’s higher sticker price and don’t want to take out loans to cover financial shortfalls because they’re afraid they won’t be able to pay them back, Fernandez said. She’s had students turn down UCLA — the most applied-to university in the nation — because of the cost.

“They don’t say oh my God, UCLA is the top public university in the nation and if I just take out a loan of $3,000 a year, I could go there or Berkeley,” Fernandez said. “They just look at that price and they just say no.”

Jacqueline Villatoro, the West Adams college counselor, shares her own story of taking out loans — $30,000 as an undergraduate — to get through UC San Diego as the daughter of a single mother from Guatemala. She spent most of it not on campus housing but on commuting to San Diego from L.A. because her mother could only find a job as a live-in nanny after the 2008 recession. Three or four times a week, Villatoro dropped off her younger sister at a relative’s house, hit the road to San Diego by 5:30 a.m. and rushed home after her noon class to pick her up from school.

She tells families that student loans can be a worthwhile investment — especially for STEM students headed for high-paying careers — but she often finds “parents are scared to take that leap.”

Over the years, fewer UC students are taking out loans, although university data do not explain why. UC undergraduates with federal loans dropped to 55,214, or 23.6% of undergraduates, in 2021-22. During the 2011-12 academic year, 85,109, or 46.1% took out federal loans, UC data show.

During her 10 years as a college advisor, Villatoro said she’s seen financial aid packages covering a smaller share of rising college costs. Pell Grants, for instance, pay for less than 30% of the cost of four-year public colleges today compared with 75% in 1980 — prompting a national campaign to double the grant.

But even though UC’s total cost of attendance is highest among the state’s three public higher education systems, its campus institutional aid is also the largest, she noted. That often results in smaller financial shortfalls.

As the Supreme Court weighs affirmative action, the University of California’s struggle with diversity since a 1996 ban offers lessons.

Jonathan’s unmet need for UC San Diego, for instance, is $4,000 — but about $14,000 at San Francisco State, whose cost of attendance is considerably lower. That’s because the Bay Area campus offered no institutional aid while UC San Diego is providing a $10,368 grant.

More money in the future

UC is stepping up its financial aid both systemwide and at individual campuses. The UC regents raised tuition for incoming undergraduates beginning last fall and set aside a larger share of the new revenue — 45% — for financial aid. That raised an additional $16 million for UC’s need-based financial aid program, which disbursed a total $864 million in grants in 2021-22.

UC President Michael V. Drake has also launched a “debt-free path” program to provide students with enough grants and work-study opportunities to cover the cost of college without loans. UC officials are phasing in the program, planning to offer it to one-quarter of new incoming students this fall and all undergraduates by 2030, said Shawn Brick, UC executive director of student financial support.

Additionally, Gov. Gavin Newsom and state legislators have expanded Cal Grants and scholarships for middle-class students to cover more living expenses and tuition. The expansions could take effect next year depending on the state’s revenue projections.

A Pell Grant change is expected to increase the number of eligible students while simplifying the complicated application. UC projects as many as 11,000 additional students could qualify for a Pell in 2024, Brick said.

All of which could help UC stay in the forefront of affordable education. The proportion of UC students in the bottom 30% of income levels — about $66,000 a year or less — continues to grow, Newman said.

“I think there’s a lot for the university to be proud of, but we’re not going to rest on any laurels,” Newman said. “When we see those [Pell] numbers go down, we get very concerned about it.”

Jonathan, for his part, still dreams of attending UC San Diego. He imagines himself pursuing his love for science — maybe physiology or human biology, a fascination first sparked by watching “Grey’s Anatomy.” He yearns to leave his L.A. confines and start an independent life in a new environment. He would love to have his own place to study, even look out of a dorm window and see the ocean.

He has about a week left before the nation’s May 1 college commitment day. Maybe, he says, a miracle will happen.

The federal government plans to forgive up to $20,000 in student loan debt for millions of Americans. Here’s everything you need to know.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.