Commentary: The latest publishing mega-merger might kill off small presses — and literary diversity

When it was announced last week that Bertelsmann, the parent company of Penguin Random House (PRH), the largest book publisher in the U.S., was going to acquire the third largest, Simon & Schuster (S&S), to form a mega-press (PRHS&S?), the outcry was swift and plentiful.

Consolidation in the book industry is never popular, but at a time when diversity — of employees, authors, books and opinions — is being scrutinized in every corner, it feels especially ill-timed. There is also the prospect of an incoming administration less friendly to monopolies. A bald attempt to dominate a precarious business, the imminent merger might capture the attention of the antitrust division of the Department of Justice. It should.

It should also worry the fragile ecosystem of small independent publishers — like me — who are vying for the same shelf space in bookstores but have none of the resources of PRHS&S. And ultimately, it should worry any reader hoping to discover voices or opinions they haven’t heard before.

Bertelsmann knows this all too well; that’s why it guaranteed the seller, ViacomCBS, a termination fee in case of government intervention. PRH Chief Executive Markus Dohle’s statements have downplayed the power that will now be concentrated in a single entity — arguments that even in a post-fact world should raise everyone’s suspicions about his motivations.

Dohle told Publishers Weekly that PRH’s market share is about 14.2% and Simon’s 4.2% of the market if you include self-publishing. This gives every title equal weight, regardless of sales. Here is context Dohle would have us omit: In 2019, PRH had 215 books on PW’s hardcover bestseller list and 93 on its paperback list. That accounts for 39.7% and 27.8% of the bestsellers respectively. Add in S&S titles, and you’ve got just under half of 2019’s bestselling hardcovers and more than a third of paperbacks. That’s a more realistic indicator of true “market share.”

ViacomCBS has announced plans to sell Simon & Schuster to publishing giant Penguin Random House LLC for a whopping $2.18 billion next year.

Going toward motive, Bertelsmann points to the dominance of Amazon (a company that could probably buy all of PRHS&S and launch it to the moon without touching cash reserves) as the impetus behind supersizing. A bigger company can negotiate better terms with the megalith, hold the line against its profit-busting discounts. This logic, wedded to the capitalist myth of the survival of the fittest at all costs, conveniently ignores the fragility of publishing. PRHS&S won’t slow Amazon’s roll for a heartbeat, but it will help more PRHS&S titles become bestsellers. So we know who benefits. Who loses?

Authors, for one. The Authors Guild strongly condemned the deal in a statement, claiming “there would be fewer competing bidders for their manuscripts, which would inevitably drive down advances offered…. The history of publishing consolidation has also taught us that authors are further hurt by such mergers due to editorial layoffs, canceling of contracts, a reduction in diversity among authors and ideas, a more conservative approach to risk-taking, and fewer imprints under which an author may publish.”

These concerns dovetail with another major trend in the book industry, an increasingly heavy reliance on two cash cows: bestsellers and backlist titles. This two-pronged approach favors giant companies that can acquire prestige imprints — thus securing the catalogs of Hemingway et al. — and pay enormous advances for ex-presidents and the like. As the critic Ron Charles stated in a fiery article, “In the future that Bertelsmann celebrates, we can all read anything we want so long as it’s a bestseller by John Grisham.”

This is the possibility that sends shivers down the spines of most of us involved in this semiquixotic business. Diversity of opinion, experience, literary style and audience is at the heart of the book world, especially independent booksellers and librarians.

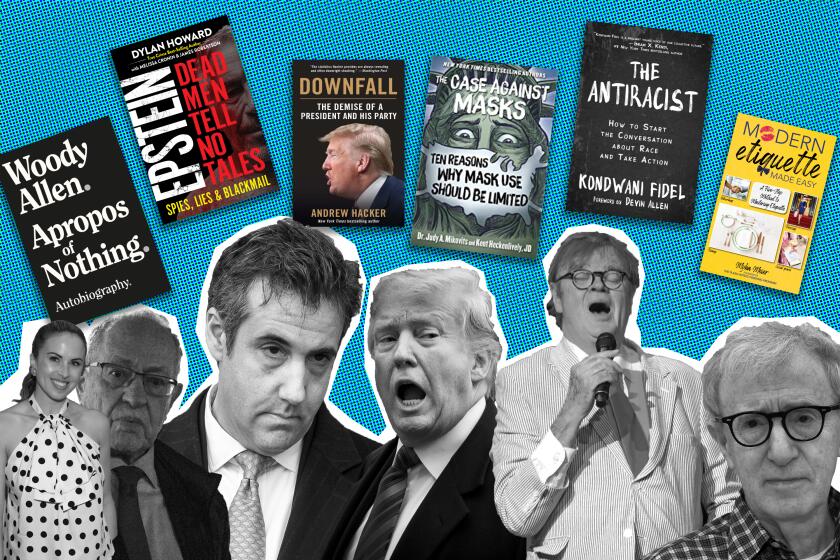

How Skyhorse Publishing became a house of last resort for Dershowtiz, Keillor, anti-vaxxers and anti-maskers — and a cancellation target itself.

And that’s what concerns me most, personally. I’m the founder of Open Letter Books, a small publisher of translated work. I’m also an editorial consultant at Dalkey Archive Press, which for nearly 40 years has supported innovative authors — many of them jettisoned by big publishers because of middling sales. Dalkey merged with Deep Vellum, a nonprofit press based in Dallas with a commitment to publishing literature from around the world. That should be the merger everyone’s talking about, a joining of forces to better take on the task of publishing new and (commercially) challenging work.

Seeking out these “new voices” has been the singular thrust of my two-decade-long publishing career. Writers like Svetlana Alexievich, Mathias Énard, Dubrakva Ugresic, along with “experimental” American authors and numerous rediscoveries. These are the authors who are the mostly likely to suffer under PRHS&S.

They’ve already suffered, in fact, under a system that increasingly fails to reward even the 1% of promising talent. Twenty years ago, a debut author — say, Jonathan Safran Foer — could get six-figure advances from commercial presses on the regular. But a shrinking number of publishers means a decrease in competition.

Contrary to the traditional understanding of antitrust law, this lack of competition doesn’t inflate consumer prices; it decreases labor costs. In other words, it disadvantages writers. Nowadays, the Big Four might not even make an offer for those big literary debuts. These are not guaranteed hits, after all, and it’s much harder to drum up buzz by having a bunch of editors bidding against one another at auction. Which they often aren’t, because they all work for the same four houses. (PRH imprints are allowed to bid against one another but only to a point.)

That’s where publishers like me figure into it. We may not be big shots — unless we’re being lumped into statistics to help Dohle make a point. But we have our function as small gears underpinning Consolidated Publishing. Here’s the modern career trajectory for a literary author in any language: get a few pieces into literary magazines, make a deal with a small independent press, sell a more than respectable number of copies, get snatched up by one of the Big Six-sorry-Five-sorry-Four.

For the conglomerates, the most financially prudent way to acquire authors who aren’t sure things is to treat independent publishers as farm clubs that identify and develop talent ripe for exploitation. Let the presses with the thinnest profit margins take the risks, seek out the undiscovered — the books readers didn’t know they wanted, the authors who change the way we talk about writing — and then, once they’ve proved these books can take off, just poach the authors. Simple. A winning formula.

Although everyone in books knows this dance inside and out, here are just a handful of examples of authors whom a small press took a chance on, only to lose them later to a big press: Roberto Bolaño, Nell Zink, Valeria Luiselli, Laird Hunt and Alejandro Zambra. And if big publishers can’t buy them, they just clone them. After Elena Ferrante, make Italian authors a thing, like you did with Nordic crime after “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo.”

In ‘Scandinavian Noir: In Pursuit of a Mystery,’ the critic travels to Nordic cities to investigate the society that shaped a global phenomenon.

This is especially true when it comes to literature in translation, which by corporate standards is risky. You have to pay an extra person (the translator) while knowing that the majority of translations sell poorly.

To illustrate the point, I poked into a translation database (which I maintain at PW) and surveyed all translated book sales in a randomly chosen month — January 2018. Of the 24 works in translation that were first published that month, only four sold more than 1,000 copies. Three of the four were from Penguin; the fourth was from HarperCollins.

There are two potential conclusions to draw from his data set: 1) the most powerful companies know which books to bet on or 2) the most monied companies determine what is read. Call me cynical, but I’m inclined toward the second.

Here’s my darkest vision of this merger: The first post-COVID-19 gathering of the Winter Institute, the only formal convention bringing together publishers and booksellers (now that BookExpo might be permanently retired), will be dominated by PRHS&S. They will have special dinners, busing booksellers to fancy venues every night to explain why it has the most important (meaning sellable) books over shrimp scampi. Meanwhile, the true laborers of the book industry — those who hustle and work the angles, who take the greatest risks and reap the paltriest rewards — will barely get any bookseller facetime at all.

Amazon may indeed be a threat to all publishers (and many other industries too). But its greatest threat is not to Simon & Schuster or HarperCollins. It’s to the indie publishers who can’t afford Jeff Bezos’ terms. These two giants, PRHS&S and Amazon — helped along by COVID-19 — could put any number of presses out of business, further reducing the diversity of voices available to readers like you. And that’s exactly what we should stand against in 2021.

Post is the publisher of Open Letter Books at the University of Rochester.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.