Review: Kathryn Davis turned grief into a glimmering memoir like none you’ve ever read

On the Shelf

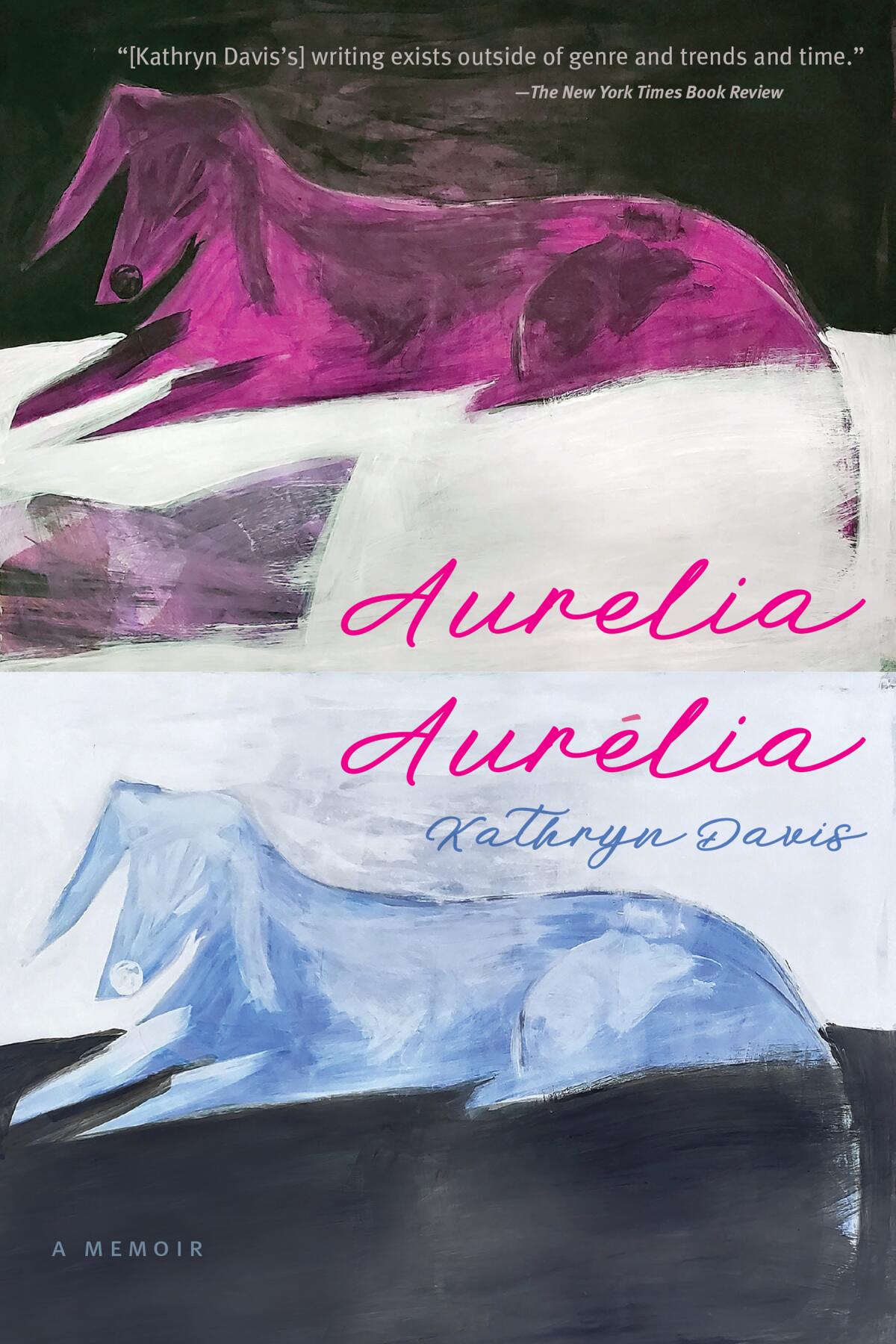

Aurelia, Aurélia: A Memoir

By Kathryn Davis

Graywolf: 128 pages, $15

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

One afternoon in my freshman year of college in Ann Arbor, Mich., I popped a little orange mescaline pill in the bathroom of the copy shop where I worked for a season. As winter dusk arrived depressingly early, I met a friend who had also taken a little orange pill. We wandered the slushy streets as evening came and Christmas lights twinkled. I remember stopping at a house under construction, its windows dark and hollow, and having the zinging revelation that everything — everything — is in some state of in-between.

It’s one of those observations that seems obvious and silly when you are in the practical, everyday world, but when you are tripping on synthetic peyote resembles pure, sparkling chunks of truth. Reading and rereading novelist Kathryn Davis’ new memoir, “Aurelia, Aurélia,” I felt revisited by this crystal-clear realization — over and over again.

Davis’ novels have often featured wanderers and seekers, allegories of self-exile and scenes evicted from the tangible world. This tendency to sidestep reality has allowed her to successfully transcend the conventional let-me-tell-you style of memoir in favor of something rarer, more ethereal.

It could be said that “Aurelia” centers on the death of Davis’ second husband, Eric Zencey, a writer and ecological economist. His presence and imagined haunting reverberates throughout. The couple in bed, drinking coffee, reading the paper. A silent, stewing fight on a rainy camping trip. Davis washing her immortal beloved’s body, postmortem. The coroner coming to collect his “heft and substance.”

As editor and annotator of this new edition, Merve Emre leads the reader to a new understanding of ‘Mrs. Dalloway.’

But it is also about Davis’ cultural preoccupations — Hans Christian Andersen; Ingmar Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal”; Beethoven’s Bagatelles; “Brigadoon”; kinhin (Buddhist walking meditation); dachshunds. We learn only in glancing details about Davis’ early life — an illness, a gun her father kept hidden in a workbench, a goldfish that committed suicide. These puzzle pieces mesh to form not a cohesive life but rather a strange whoosh of movement that evokes metamorphosis, a shift of mind and memory.

The first chapter’s title, “Time Passes,” indicates the kind of memoir Davis’ will be. It is borrowed from the middle section of Virginia Woolf’s “To the Lighthouse,” in which a decade is collapsed into a dozen and a half pages. Davis writes about it explicitly: “One minute you’re in the drawing room with Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay, the next minute you don’t know where you are. One minute you’re a girl who thinks she’s an adult. The next thing you know, you’re on the threshold of a world that seems impossible to enter, even though you have no alternative.”

Woolf’s middle section famously elides the great civilizational rupture of World War I. Davis’ time passes in the aftermath of her own severance from order, the loss of her anchor to the everyday. “When someone you have lived with for a very long time dies,” she writes, “memory stops working its regular way — it goes crazy. It is no longer like remembering; it is, more often, like astral projection.”

Like Woolf’s portal from the windowsill to the seaside, “Aurelia” is set in a cerebral atmosphere that lives in the “ghost-moment,” or that time between a piano key being depressed and the dissipation of its reverberating note. This is not a Mary Karr memoir full of snappy dialogue and intricate scenes conjured up from memory. It is not the multiclause essay construction of Nabokov’s “Speak, Memory,” nor the corporeal exploration of female bodies of Rachel Cusk’s “A Life’s Work.” Davis’ slim but dense memoir is beyond scene, beyond self, beyond body.

When I think of all the stiff pronouncements I’ve made demanding truth in memoir, I’m inclined to hang my head.

It is in some ways a documentary of feeling dislodged from life, questioning how it is we ended up in the containers we inhabit, moving around in the places we find ourselves. “I wish sometimes to be less an imagination and more a person,” Davis recounts writing. (In a journal? In a letter? We are not told. It does not matter.) “I didn’t know where or what I was, really. I lived in a body but there was part of me that seemed, like Virginia Woolf, capable of functioning without one.”

You do not read “Aurelia, Aurélia” so much as you let it move you, move past you. This feeling of witnessing passage — from where to where we do not know; it does not matter — is hidden within the book’s title. “Aurelia,” Davis reveals in the final chapter, is a Latin word translated from the Greek for “chrysalis.” It is also the name of the student ship that took the author from America to Europe when she was a romance-obsessed 16-year-old. And it is the title of French poet and novelist Gérard de Nerval’s self-documentary of transition into madness.

These seemingly disparate facts are connected by Davis’ own loose memories, strung together by an assured stream of consciousness. When Davis allows them proximity, they cohere into a feeling of grief infused with pattern and meaning. To read it is to move through the darkened interior of the author’s mind with your hands out, feeling for objects, listening for Beethoven’s Bagatelles, inviting haunting, all to make some sense of the invariable fact that lives are bounded but the mind is limitless.

Pariseau is a writer and editor in New Orleans.

Bethanne Patrick’s March picks include works by Bob Odenkirk and Elena Ferrante, as well as an Indigenous punk memoir and magical African allegories.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.