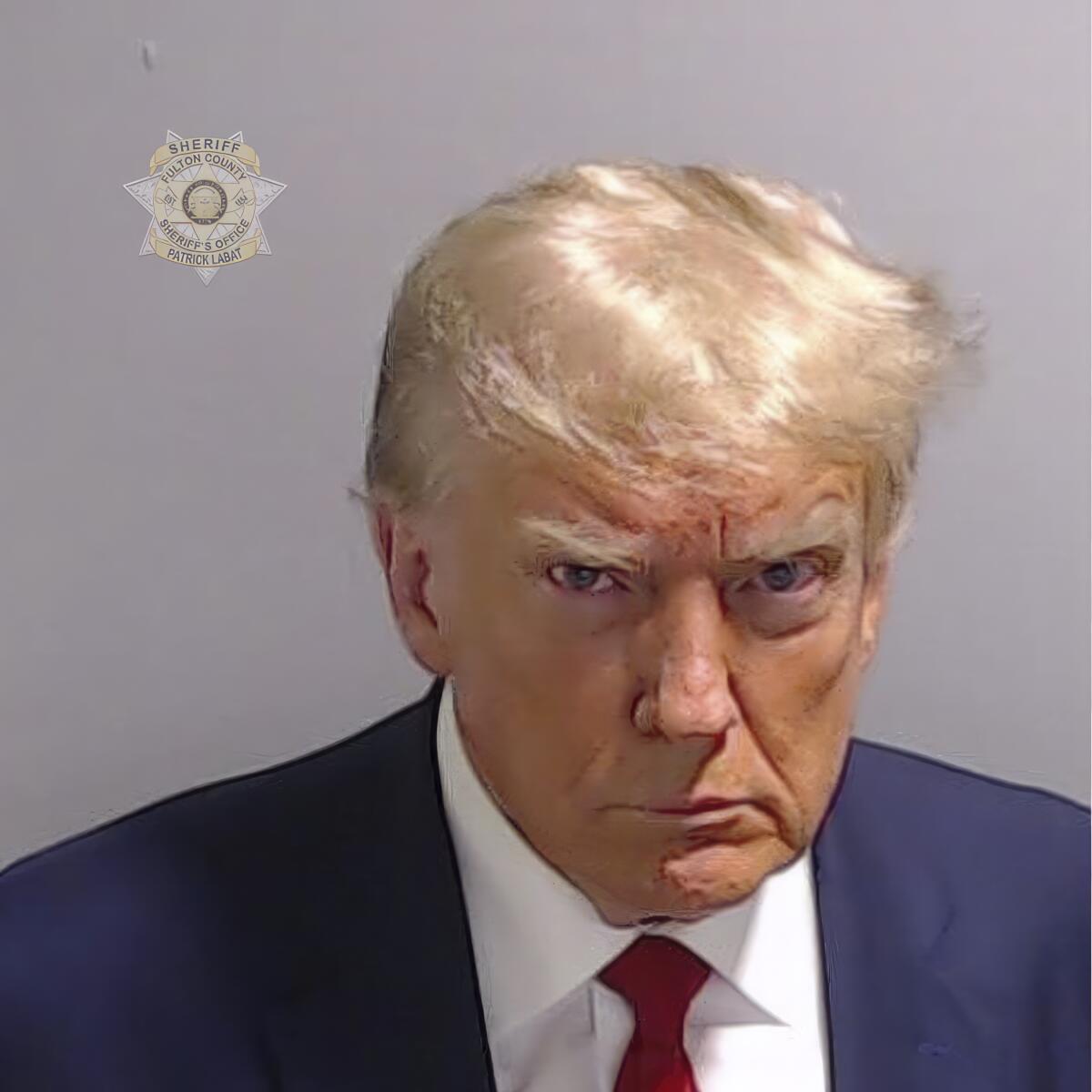

Commentary: Donald Trump’s campy mug shot gives Andy Warhol’s infamous mural some competition

Sometimes, a routine police-booking photograph of a criminal suspect gets pushed to the popular culture foreground on the crest of an accused offense — Jane Fonda with a raised-fist power salute mocking an arrest for a falsified drug charge, for example, or Charles Manson with a very real swastika carved into his forehead. Once the heated news cycle moves on, the photograph sinks back into relative obscurity, pulled out now and then for related updates.

Mug shots get filed, but their resonance bends toward fleeting. That changed last Friday.

Release of the Fulton County Sheriff’s Office mugshot of the disgraced 45th president of the United States, indicted for an attempt to overturn the Georgia results of the 2020 election, instantly catapulted to iconic status. By virtue of 13 felony charges for racketeering and conspiracy, this picture will last.

The harshly lighted photograph of Donald John Trump was snapped by an unidentified county official. The mug shot shows the suspect’s head lowered as if to obscure a jowly double-chin, eyes narrowed into a glare, lips firmly pursed and yellow pompadour swirled into a cotton-candy crown. Missing a paired profile shot, which is common to the police-photograph genre, it bumps into second place virtually any of his other innumerable portraits, presidential and otherwise.

The pose was surely staged at least as carefully as the fake Time magazine covers that he once produced to con the gullible. Imagine him preening in front of a mirror in the days leading up to his scheduled arrest, trying out various grimaces, the better to determine which might best convey “never surrender!” to his supporters.

That declaration is what he quickly posted to 87 million followers on X (formerly Twitter) when the photo was released. The fact that his actual surrender to police custody prompted publication of a never-surrender visual is a splendid irony — albeit one apparently lost on the cult, given the $7.1 million his campaign says it raised within 48 hours.

Never surrender — unless you are doing exactly that?

Social media soon lit up with comparisons to Hollywood’s so-called “Stanley Kubrick stare,” offered by deranged and violent characters in the vaunted director’s filmography — like Malcolm McDowell in “A Clockwork Orange” and Jack Nicholson in “The Shining.” However, not only is the thought that this cruel and petty coward is some sort of unstoppable supervillain too absurd to take seriously, it is also belied by the pile-up of arrests for 91 criminal charges (so far) in multiple jurisdictions, plus his May 9 conviction for civil liability in what the judge described as the rape of E. Jean Carroll.

What’s more, the ridiculous mug shot made me laugh, not cringe. For me, a better analogy than Kubrick lies elsewhere.

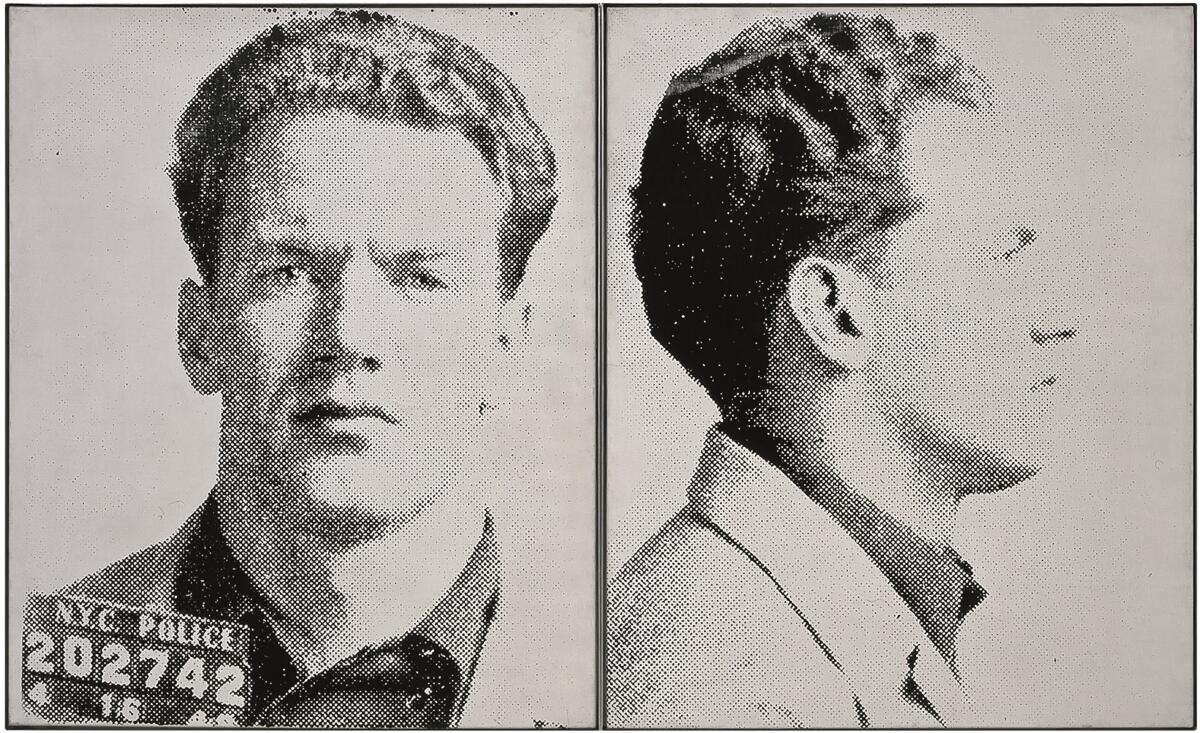

Before last Friday, the most enduring mug shots in modern American culture were Andy Warhol’s “13 Most Wanted Men,” born as a monumental mural for crowds at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. For incongruous mug shot photography, Warhol now has some real competition in the longevity sweepstakes.

More important, something resonates between Warhol and Trump’s mug shots. More than just the coincidental number of 13 wanted men and 13 felonies, it’s the projection of their own alleged criminality.

The first Southern California show of self-taught artist James Castle (1899-1977) is now on view at Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

“13 Most Wanted Men” was later elaborated into a set of paintings on canvas. “No. 6,” a two-panel work in black silkscreen ink on silvery gray ground, shows head-on and profile views of scowling Thomas Francis (Duke) Connelly, NYPD bank robbery suspect #202742. It hangs upstairs at the Broad museum, displayed along with Marilyn Monroe, Jackie Kennedy and a nifty diagram for a ruptured hernia truss. The World’s Fair portraits live on not because of the particular people pictured, but because of the artist’s stature.

The mural was Warhol’s only public art project, and it was a fiasco.

Architect Philip Johnson, who designed the fair’s New York State Pavilion, gave him the $6,000 commission for a big painting on a 20-square-foot Masonite panel that would hang on the building’s façade. The mug shot idea came from artist Wynn Chamberlain, whose cop boyfriend often brought NYPD fliers home.

Warhol had also seen the Marcel Duchamp retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum a few months earlier. The impish Dada artist’s design of a wanted poster featuring his own fabricated mug shot as a show promotion lent avant-garde pedigree.

When the mural was installed in April, fair officials blanched. Crime touted as a cultural highlight for a huge tourism event? Within 48 hours, it was censored by Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, painted over with silver paint. Rockefeller, a Modern art collector then angling for a presidential run, also may have figured that alienating Italian and Irish American communities by showcasing members’ criminality was not a winning political idea.

And Warhol’s mural was most certainly political, which is what his mug shots share with Trump’s.

Trump’s campaign hit a single-day fundraising record of $4.8 million after his booking photo was released last week, a campaign official said.

Artistically, the unlucky number 13 played on the familiar trope of the avant-garde artist as cultural outlaw, while using crude mug shots gave imaginative sheen to one of the lowest forms of photography. In 1964, camera work was barely considered an art form, never mind a medium with credibility equal to painting. (Part of Warhol’s genius was to use silkscreens to dress up common snapshots in painting-drag.) But a sharp political punch came in the implication of official sanction for the the work’s homoerotic overtones. A swish artist was trumpeting “13 Most Wanted Men,” complete with clear undertones of enthusiasm for illicit rough trade.

If that political meaning was hardly obscure, another has remained largely overlooked. Also in spring 1964, Congress was in a pitched battle over passage of the Civil Rights Act.

In support, the local New York branch of the Mattachine Society, a pioneering gay civil rights organization founded in L.A. by Harry Hay in 1950, compiled a comprehensive list of state penalties for sodomy. Sex between men was illegal everywhere but Illinois. New York imposed 90 days in jail for a first offense. Neighboring Connecticut, manifesting its separatist Puritan history, posted the nation’s most severe punishment, inflicting 30 years in prison. Pennsylvania, Warhol’s birth state, added a $5,000 fine to a mandated 10-year sentence.

Implemented or not, those malicious state penalties existed to suppress the freedom of its targets through fear. Warhol wasn’t merely a successful Madison Avenue adman and an emerging fine artist; as an active homosexual, he was also a criminal. He had that in common with the most wanted men he chose to elevate.

And Trump? His visibly stage-managed photograph is pure political theater. Legal defense for the Georgia racketeering and conspiracy charges is a steep climb (we’ve all heard the wildly incriminating tapes) so politics is pretty much all he’s got. For his first on-camera moment in a perilous case, he assumed the pose of a victimized tough guy to rally his aggrieved base.

As they say of difficult criminal trials, when you can’t pound the facts and can’t pound the law, pound the table instead. In his preposterous mug shot, Trump pounds away, looking just as fiercely enraged as he possibly can. Warhol, a master rather than an apprentice of celebrity, would surely understand. But I do wonder: Does Trump know it’s camp?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.