William Blake was called a ‘lunatic’ in his lifetime. The Getty hails him as a visionary now

William Blake was a bit of a nut. That’s partly why we like him so much.

The great British Romantic artist, whose lifespan (1757-1827) roughly corresponded with that of mad King George III, aimed to unite the powers of individual poetic imagination with complex technical skill, in order to revivify what he perceived to be art’s moribund condition. The result was sometimes a wild invention rendered in unusual materials, usually combining various printing techniques with hand coloring. Such work deviated far from customary techniques of production or using established myths as subject matter.

That many of his peers pretty much dismissed him only made Blake dig his heels in deeper. And we’re glad he did.

Denmark was in full chaotic collapse in the early 19th century. Why was its art so beautifully serene?

At the J. Paul Getty Museum, “William Blake: Visionary” brings together 104 works by the artist, plus a few by contemporaries (notably his friend, expat Swiss painter Henry Fuseli, 16 years his senior and a stalwart at London’s Royal Academy). Blake was convinced that art had been on the skids since the mid-16th century, when worldly Titian and the Venetian painters rose to prominence, so he set about trying to put things right. The result was often wonderfully weird.

Exemplary is “Satan Exulting Over Eve,” his retelling of the circumstance of humanity’s ostensible fall from the biblical perfections of the Garden of Eden. Lucifer is cast as a classically handsome youth, his nude but sexless body stretched out horizontally, edge to edge across a nearly 2-foot-wide sheet. Bat-like wings are spread wide, matching outstretched arms that wield a pointed spear and shield, backed by rolling waves of fire lighting up the darkness.

The figure hovers over Eve’s body, laid out flat on the ground in silhouette. An apple is tucked beneath the open fingers of her hand, and her head is tossed back in a death that summons up an intimation of exhausted sexual ecstasy. A monstrous serpent coils around Eve’s body, its tangled tail by her feet mimicking the splayed curls of her hair at the other extreme; the beast’s dragon-like head rests on her breast.

What’s exceedingly strange about the stunningly composed image is Blake’s choice not to emphasize the wages of sin — that is, death — given a barely articulated corpse confined to the lowest register. (She’s less than a sixth of the composition.) Instead, the focus is aimed squarely on Satan’s gratified rejoicing in his triumph as mortality’s instrument, effectively heroic in a pictorial pose of “ta-da!” (Blake used the spread-arm pose a lot.) The artist makes the scene virtually operatic, the famous British gift for theatricality turned up to a melodramatic high. Satan takes up more than half the page, his serpentine surrogate below further enlarging the demon’s prominence.

World War I is the focus of an exhibition at LACMA, where its representation as perhaps the first ‘media war’ gets examined.

“Satan Exulting Over Eve” was made through an elaborate process. Using a sticky concoction of opaque watercolors, Blake drew the image on a stiff board. He used the drawing as a kind of printing plate, stamping it onto a sheet of paper, almost like a monoprint. Ink and transparent colors were then applied to provide a detailed picture, the filminess allowing the support to reflect light and generate a subtle glow from within. Blake had long earned his living as a commercial printer — he was 38 when he made the exulting-Satan work — and he was both expert at employing standard printing methods and inventive in concocting new ones.

In works like this, Blake brings together the muscularity of Michelangelo’s drawing, the formal crispness of Raphael, Albrecht Dürer’s commitment to printmaking as a modern form and an almost medieval mysticism that predated Renaissance rationality. Since he never traveled around Europe to see other art firsthand, as was common for artists at the time, Blake knew those predecessors’ works largely through copied engravings and some isolated examples in private aristocratic collections. Limited or not, his familiarity with past art inspired new visions.

The Getty exhibition, organized by assistant curator of drawings Edina Adam and senior curator of drawings Julian Brooks, is a trimmed version of a huge one put on by Tate Britain in London, which was scuttled in 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the excellent catalog, it’s the first loan exhibition of Blake’s work to be seen on the West Coast in 80 years.

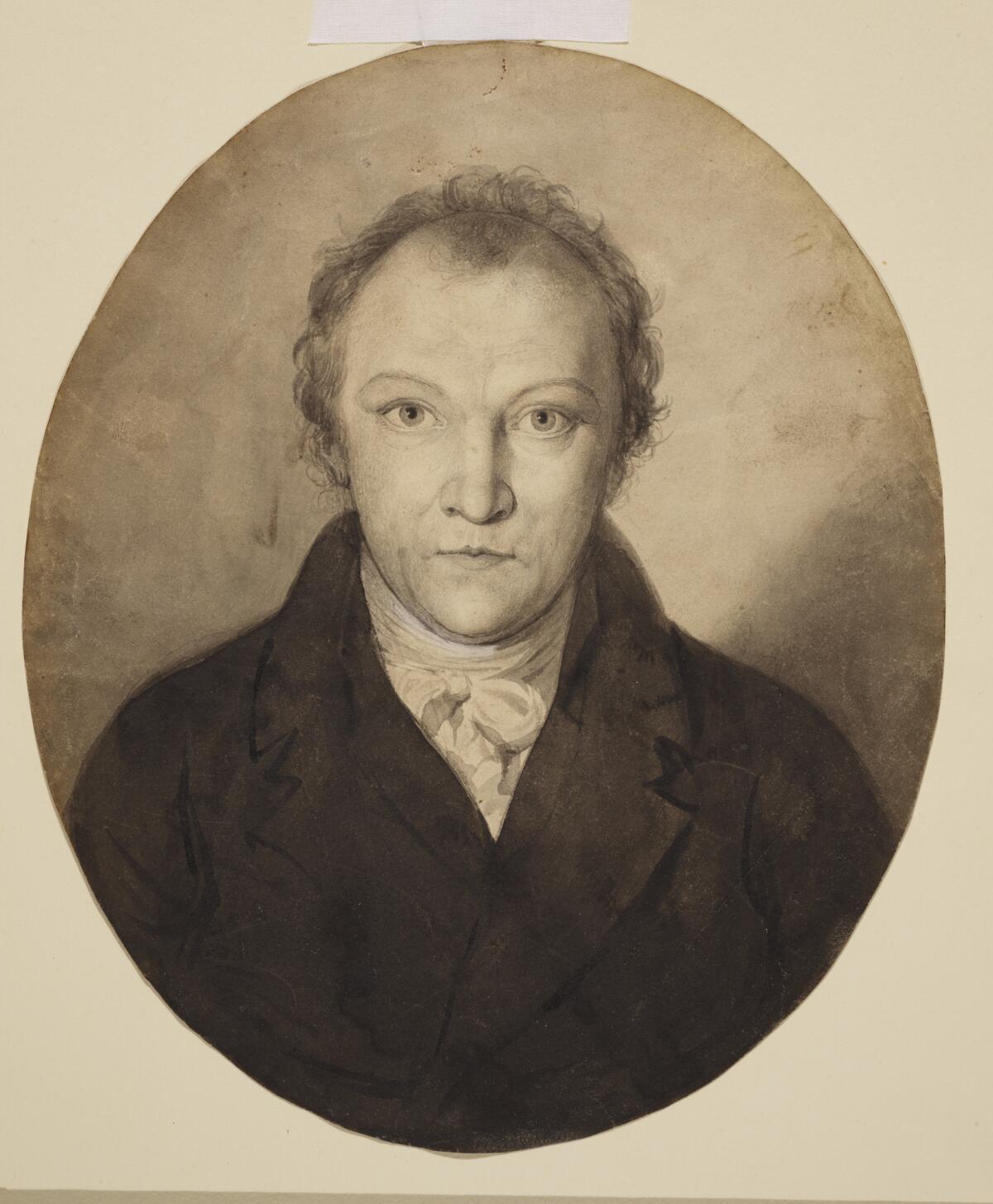

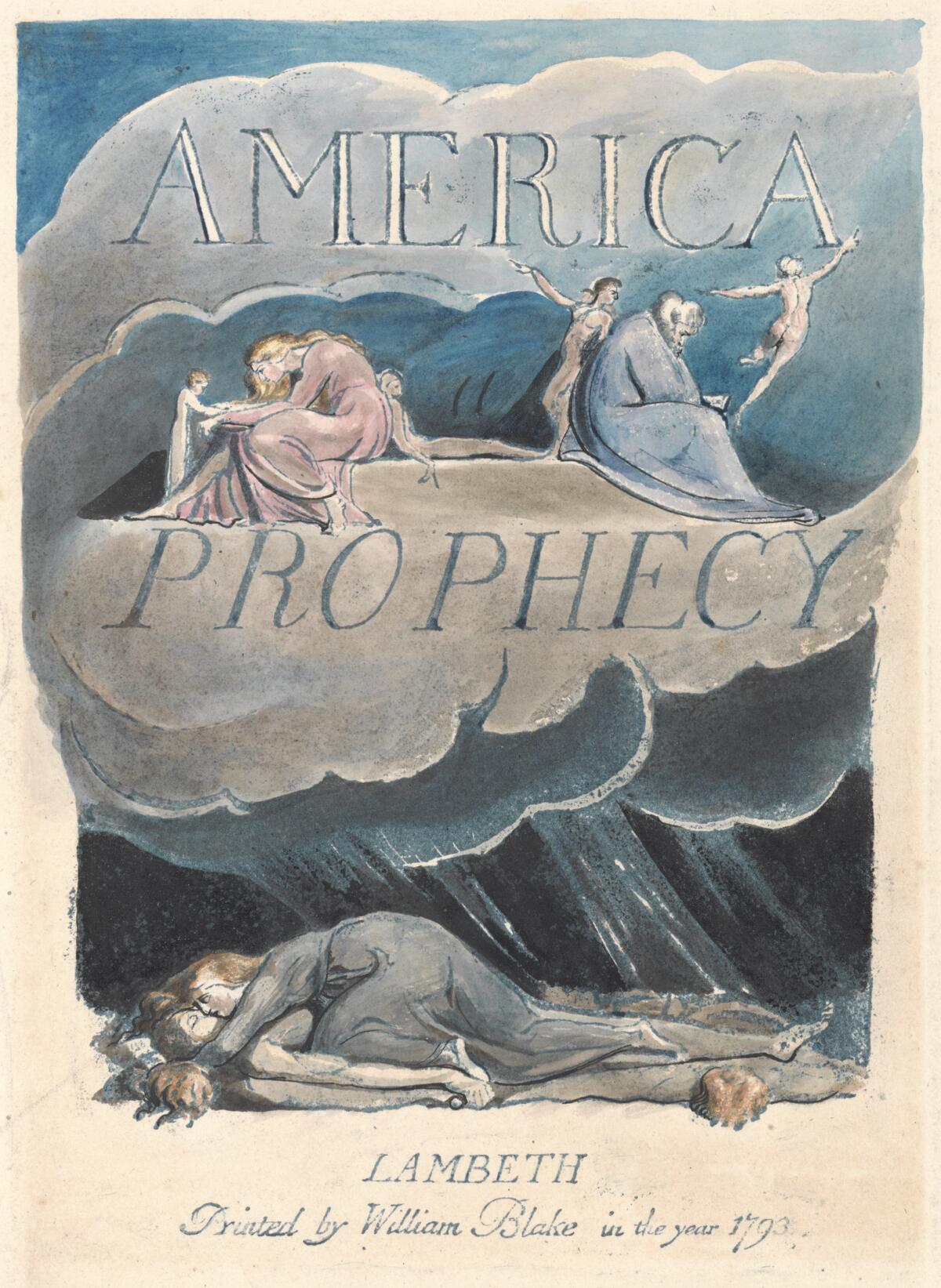

It includes “The Ghost of a Flea,” Tate’s rarely loaned, murky miniature painting in dark tempera and gold on hardwood panel starring a monstrous, human-insect hybrid looking hungrily into a bucket of blood. From the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Conn., comes a full set of 18 works from “America a Prophecy,” a book of poetry wrapping text with imagery, inspired by the revolutionary fervor erupting across the Atlantic Ocean against the British crown. (On one page, a king is said to cower when confronted by Orc, spirit of revolution, but Blake was careful to leave King George’s name out of it, fearful of being charged with sedition.) There’s also Blake’s only self-portrait, a bust-length, frontal drawing in soft pencil and fluid gray wash in which the fixed stare of the artist’s crisply rendered eyes might be thought to emit invisible electromagnetic energy beams. He’s got you in his sights.

The self-portrait is making its United States debut, 220 years after the fact. (It has barely been shown in the U.K. — odd, given the artist’s superstar status there.) Helpfully, the museum provides several magnifying lenses throughout the exhibition, which aid in close scrutiny of detailed pictures. There’s a delicacy to Blake’s touch, which butts up against the work’s sometimes dark, often apocalyptic imagery. The tension resounds.

This is the artist, after all, whose poem, now called “Jerusalem,” famously took note of the hell being produced by Britain’s roaring industrial revolution — the steadily advancing mechanization he described as creating “dark Satanic mills,” depriving poor people of their livelihood while fouling the land. Blake was a fierce critic of the social and spiritual costs of rampant, unrestrained industrial manufacturing. Yet he didn’t paint nearly as often as he made prints — the pictorial art that requires one sort of machine or another as part of its production. Rather than pretending that such debilitating economic transformations could be stopped, he chose to make art that stands as a pointed and articulate alternative.

When 2023 began to unfold, pandemic-induced art museum cancellations and postponements seemed to be behind us, as programming mostly caught up. Here are 10 memorable exhibitions from the year.

Blake left school at the age of 10, having learned to read and write, and he was apprenticed at 14 to a commercial engraver. He read widely on his own, developing a highly individual and personal worldview. Although he studied at the Royal Academy, he reviled its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds, who not only represented the British art establishment, but was instrumental in constructing it.

Blake was largely unsuccessful as an artist in his lifetime. An 1809 exhibition that he desperately organized to market his work was notoriously panned in its single review as offering “wretched pictures” produced by “an unfortunate lunatic.”

At the Getty, on the other hand, we get a reasoned procession of five sections. They are devoted to Blake’s labor as a professional printmaker working for others; an independent artist working on his own; an inventor of distinctive techniques; a figure with one foot in and one foot out of the British art world; and, finally, a visionary.

The endlessly imaginative result makes for an exhibition both unexpected and timely. In the tumultuous context of industrial revolution, think of Blake as artisanal. Today’s bloodless digital revolution, which has been disrupting things for a generation, is now being met by a wave of artists who insist on giving handmade qualities a platform. Blake, nutty or not, stands front and center as a valuable predecessor.

'William Blake: Visionary'

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: 10 a.m.–5:30 p.m., Tuesday-Friday and Sunday; 10 a.m.-8 p.m. Saturday. Through Jan. 14, 2024.

Info: (310) 440-7300, getty.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.