Review: Rapt in Byzantine gold at Getty Villa’s ‘Heaven and Earth’

Think of Byzantium, and a color leaps to mind. That color is gold.

The empire ruled from the crossroads of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea for a thousand years between AD 324 and its final collapse in 1453. At the Getty Villa in Pacific Palisades, where a rare and stunning exhibition of Byzantine art recently opened, gold is everywhere.

It’s the ground on which biblical scenes unfold, from the tender nativity of Jesus to the brutal Passions and miraculous resurrection of Christ. It’s in the air breathed by saints speaking to the faithful from painted manuscript pages.

It’s in the threads woven into tapestry cloths used in liturgical rituals on church altars, and it colors the mosaic tiles built into floors and walls of buildings. And of course it’s the substance of delicate jewelry and lavish body ornaments — of golden rings, arm cuffs, necklaces and earrings.

PHOTOS: Best art moments of 2013 | Christopher Knight

Gold is even suggested in simpler, more humble but no less beautiful objects such as glazed clay dishes and bowls. The linear images of birds, dancers or lions are made from incising into the pots’ red clay, but the shimmering slip-glaze that surrounds the figures is mostly in varying shades of yellow. Sometimes the glaze is even subtly iridescent.

Why gold? On the evidence, because of its capacity to serve two rulers: The exhibition is titled “Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections,” and its 187 objects together demonstrate how gold can represent power that is both earthly and heavenly at once.

The Byzantine Empire is fundamentally noteworthy because it was the first in which the secular power of the state fused with the religious authority of Christianity. In the West, not until the U.S. Constitution came along, were the two finally uncoupled.

When Emperor Constantine moved the capital of the Roman Empire east to the Bosporus Strait joining Europe and Asia, he left behind the tangled mythologies of Greco-Roman religion. Back in Rome, mere mortals had been practically a breed apart from the dozens of indifferent deities romping all around them. But Christian monotheism, which Constantine embraced, changed all that.

PHOTOS: The most fascinating arts stories of 2013

Spirituality, the search for the sacred in humanity, was in its way a whole new concept. Gold emerged as a bridge. Its everyday value as currency was intrinsic. But it also possessed distinctive visual properties. Rome’s old material practicality was linked to new spiritual abstractions.

Gold is all hard surface with no spatial depth. Yet when used in a painting or mosaic, it shatters the rational articulation of space.

The mosaic body and clothing of the apostle Andrew in a magnificent, late-11th or early-12th century wall decoration is an elegant network of outlines. The life-size striding figure’s marvelous animation is driven by linear whorls at his bodily joints. Almost like origami, the weightless, paper-thin figure traverses a shimmering golden field.

Gold’s light-reflective qualities, especially in direct sunlight or in darkened rooms illuminated by candles or oil lamps, can create spectral illusions of infinity. You seem to be able to touch the ineffable with your hand.

To represent the dual nature being claimed for Christ — both man and god, the earthly and the divine — what could be more useful?

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

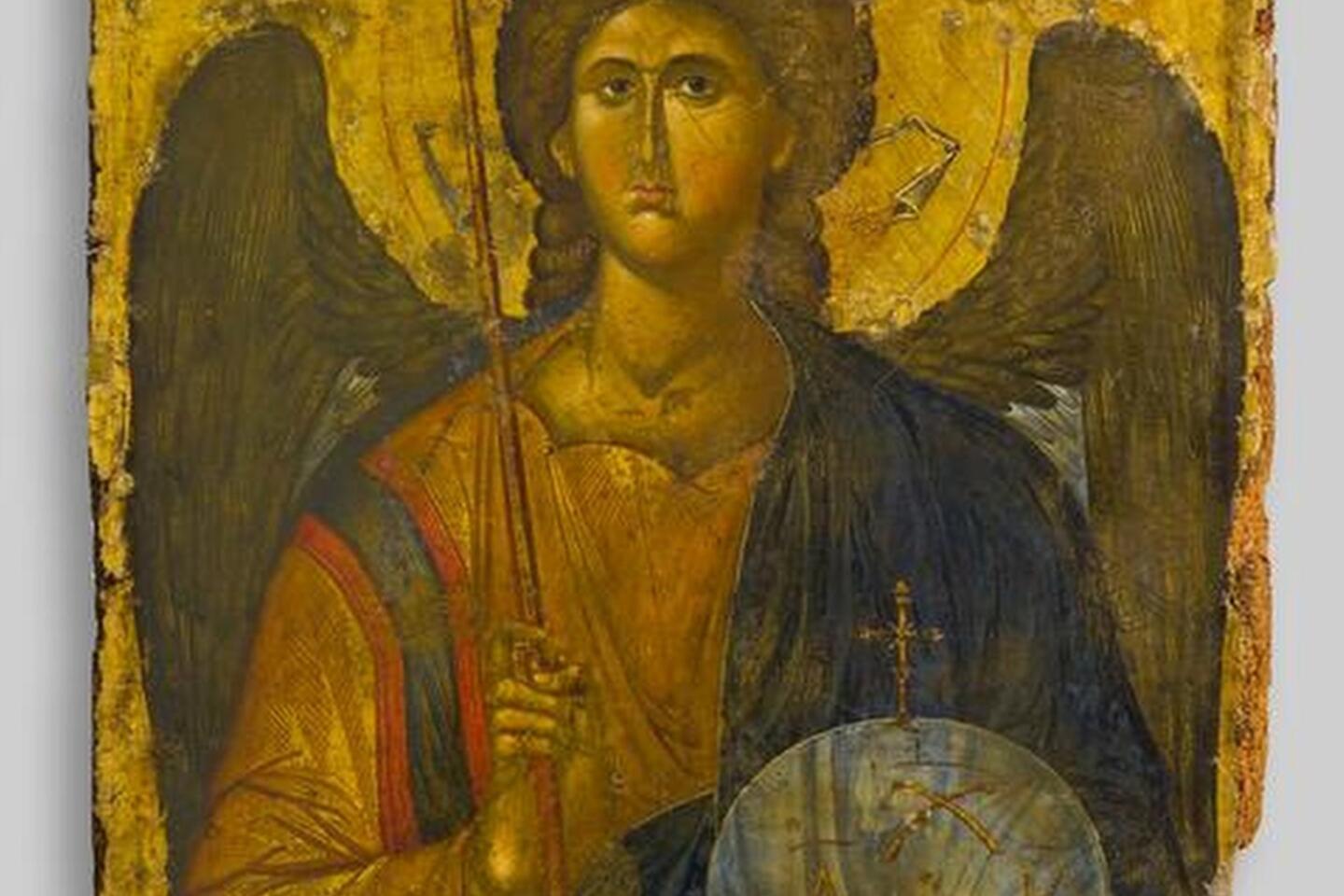

The second of the show’s three galleries is the most powerful. A dozen or so gilded icons, together with several mosaics, manuscript illuminations and a fragment of a wall fresco, come from different centuries and various parts of the far-flung Byzantine Empire, which encompassed much of the Mediterranean region. (The show is installed thematically, not chronologically or geographically.) But they all embrace a linear style of rendering, flat and two-dimensional, that downplays naturalism in favor of abstraction.

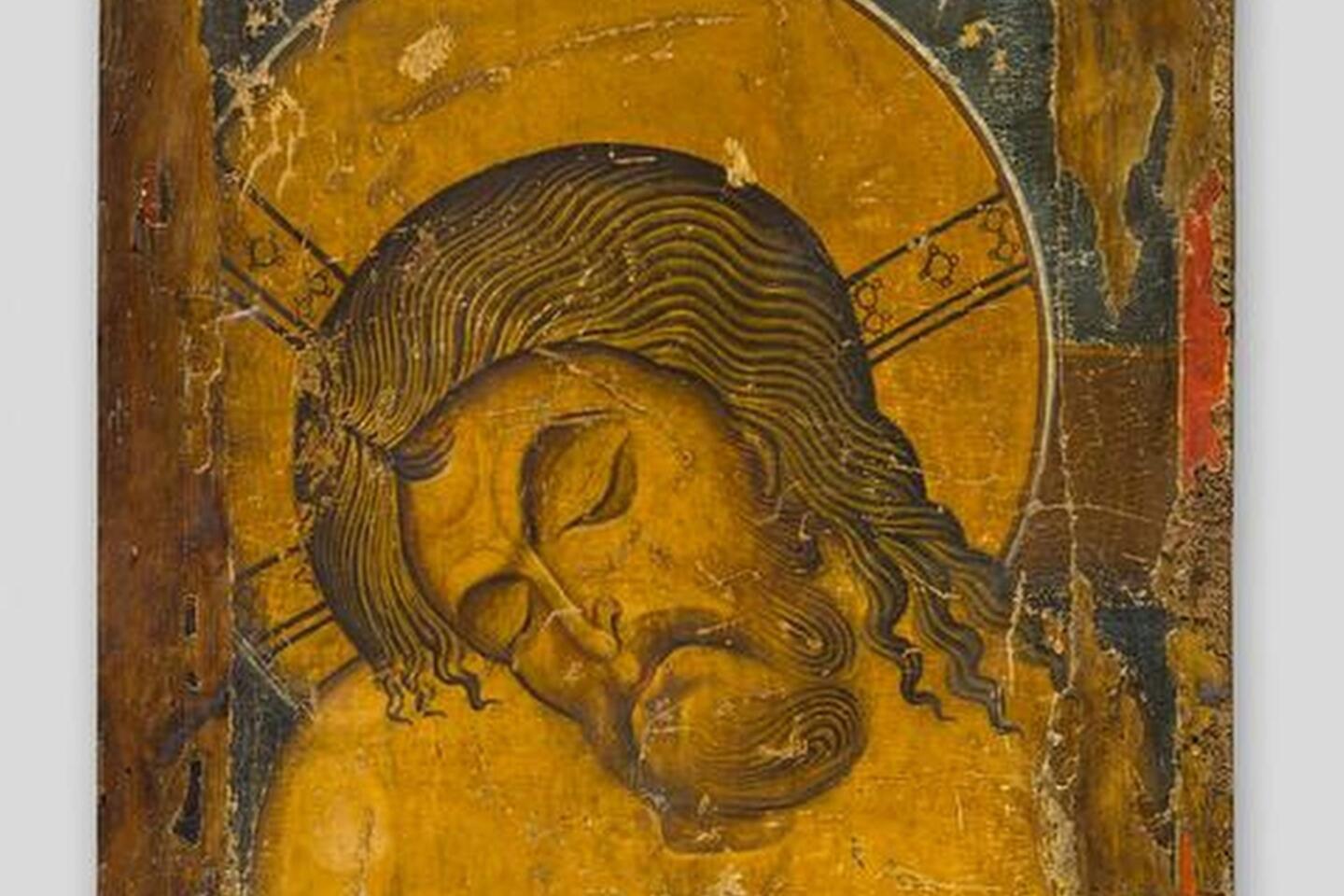

The face of the dead Christ, his head sunken into his shoulders, in an icon of “The Man of Sorrows,” is surrounded by rivulets of hair and beard drawn as meandering, rhythmic patterns. An orb adorned with symbols for Christ as Eternal Judge represents the heavens, nestling in the left hand of Archangel Michael, but it is less a dynamic sphere than a swirling disk. Both Christ and the angel are low relief forms set in gilded realms rather than worldly figures full of flesh and blood.

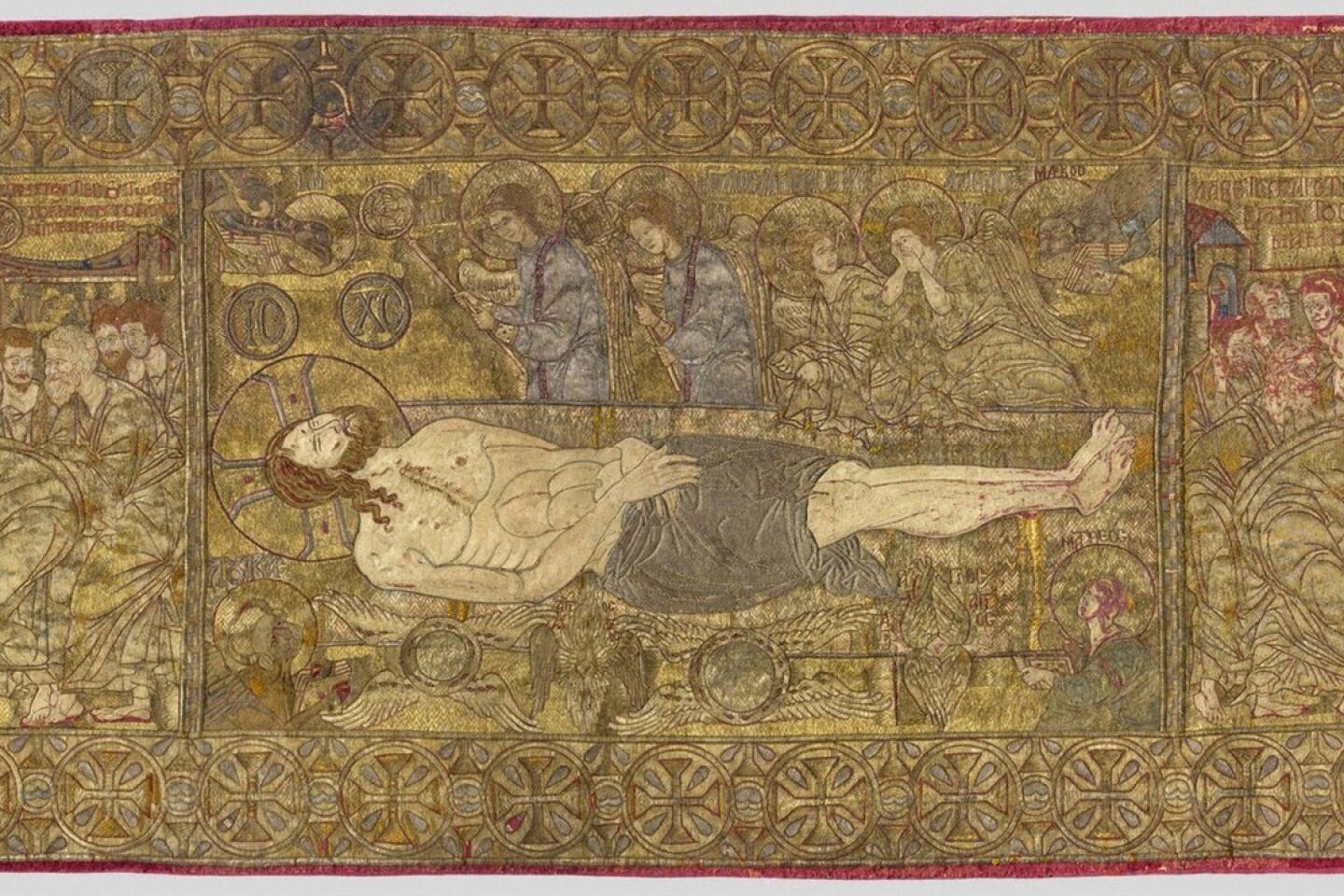

Christ is laid out on a tomb slab on an exquisite, 6-foot-long woven liturgical cloth, one of the great treasures made near the empire’s end. He is flanked with Communion representations of the body and the blood. The ensemble creates an elaborate, two-dimensional drawing in glittering embroidery thread.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

Throughout, gold is a self-evident emblem of material wealth, with all the mundane clout and control that implies. Yet it also carries the pictures’ mesmerizing abstraction, which catapults the spiritual end of this art’s spectrum.

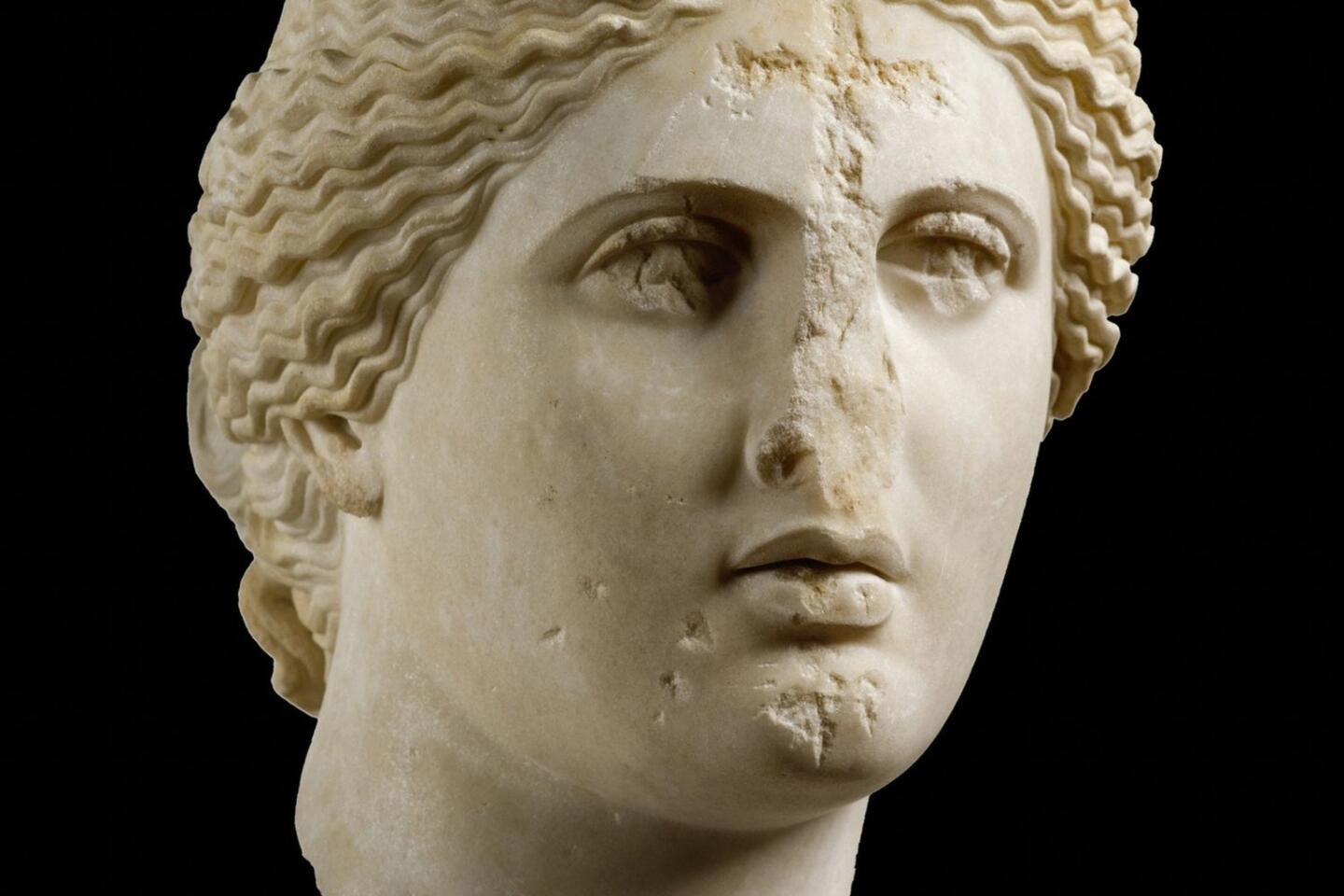

The show even includes religiously inspired graffiti of startling violence. A first-century marble head of the pagan goddess Aphrodite — a Roman copy of an elegant Greek original by Praxiteles — was literally beaten up. Her nose was broken off to disfigure her beauty, her eyes gouged out to metaphorically blind her and her mouth scarred to stop her from speaking. A cross was crudely chiseled into her forehead.

Take that, pagans!

The exhibition’s three galleries touch on the development of Byzantine art from ancient Greece through various iconoclastic controversies and on to Constantinople’s occupation by crusaders — which seriously weakened the empire — until the final fall and takeover by the Ottomans. That’s a lot of territory to cover. The show can offer only a thousand-year sketch.

ART: Can you guess the high price?

Its fat catalog, with 25 essays and 95 contributors, offers scholarly detail. (A concurrent show of 17 Byzantine manuscripts and illuminated leaves, including one discovered to have been stolen from a monastery on Mount Athos more than 50 years ago and now slated to be returned to Greece, is at the Getty Center.) Perhaps its chief drawback is an over-emphasis on the Hellenistic roots of Byzantium, which fills the first room.

There is certainly truth to the claim. For example, a big, handsome, carved-marble table support shows the Greek hero Bellerophon riding his winged steed Pegasus to slay the mythic monster, the Chimera. It’s easy to see the narrative as a foreshadowing of St. George and the dragon from later Christian myth.

Yet the evolution and flowering of Byzantine art was more a result of shedding Hellenistic naturalism than of building on its precedents. The beat-up Aphrodite sculpture is eloquent evidence of that. The over-emphasis on Hellenism may simply reflect the show’s organization by Athens’ great Benaki Museum and the Ministry of Culture and Sports, both agencies of the Greek government.

Byzantine art wrapped a linear style of powerful abstraction in gold. That’s beautifully encapsulated in the Getty Villa’s galleries, comprising what is reportedly the largest show of its kind ever to be seen in Los Angeles.

christopher.knight@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.