Can women break the antihero’s hold on TV?

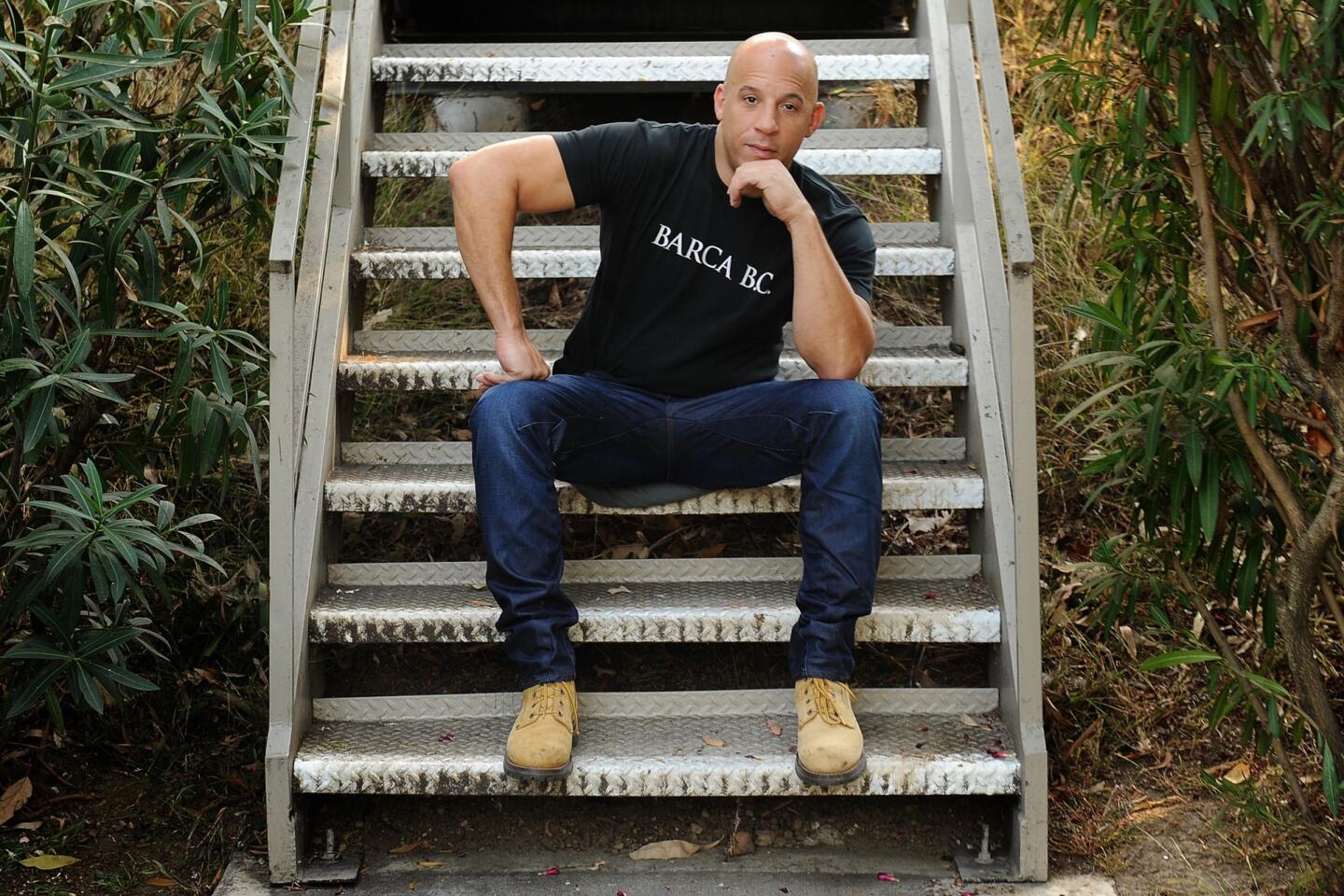

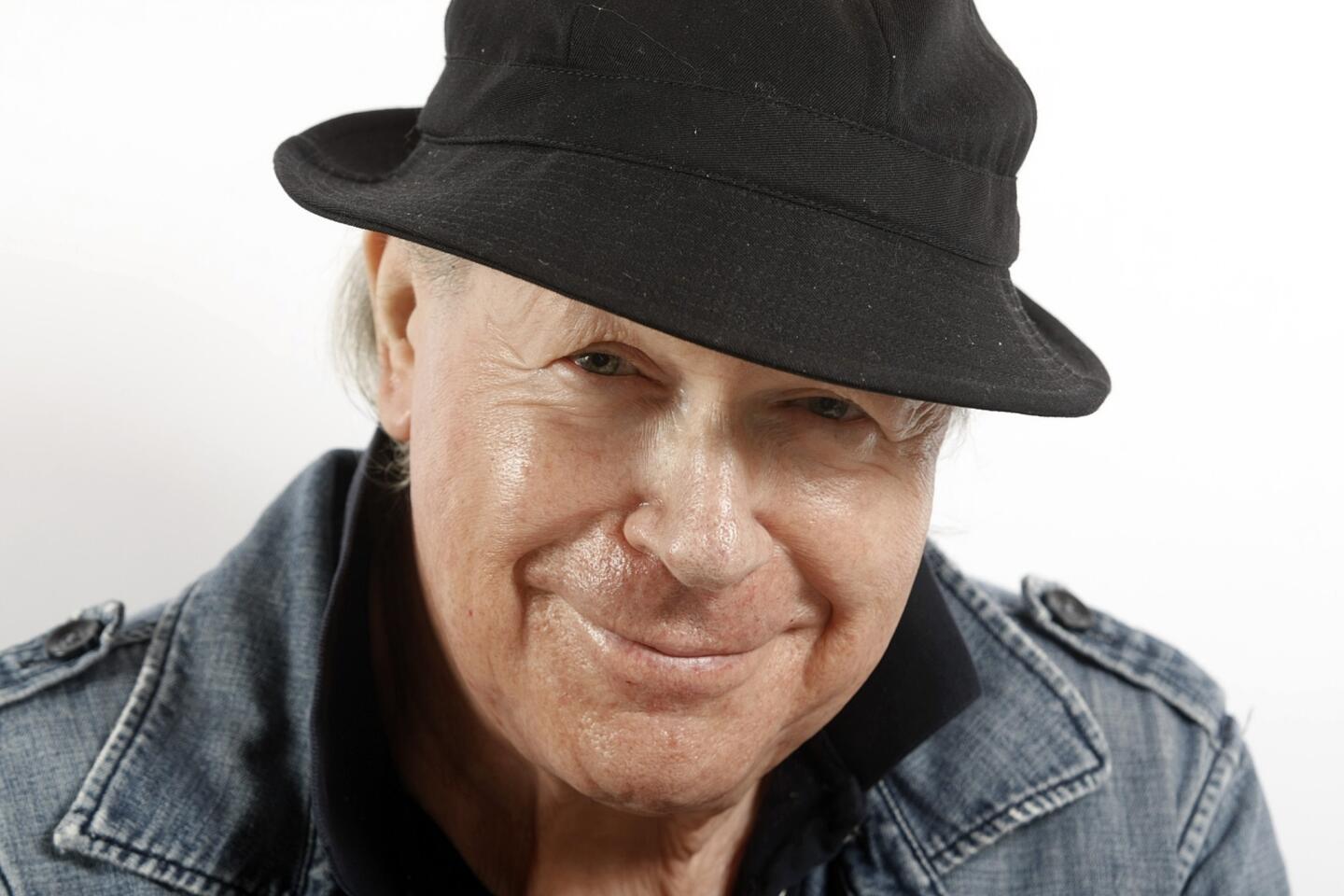

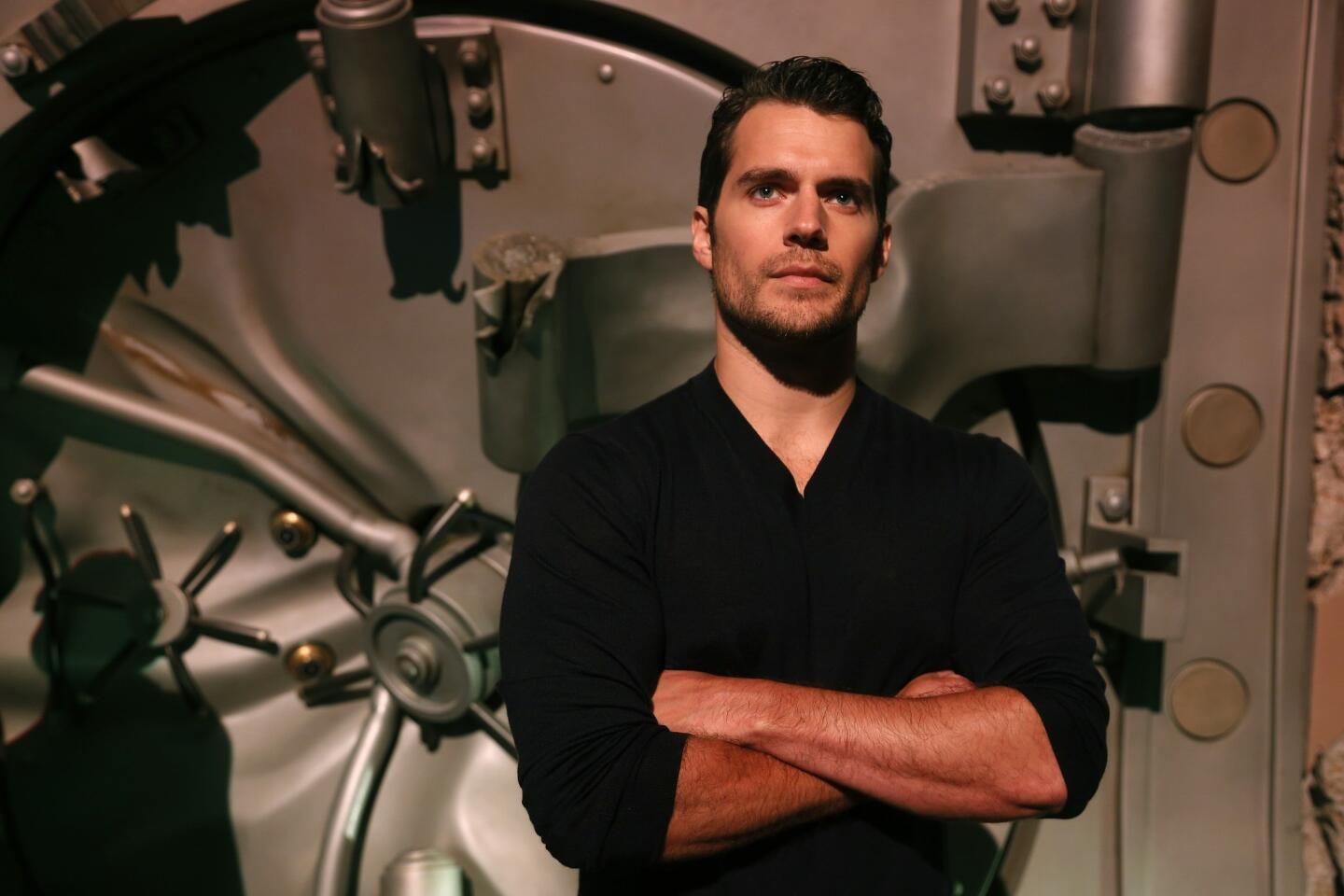

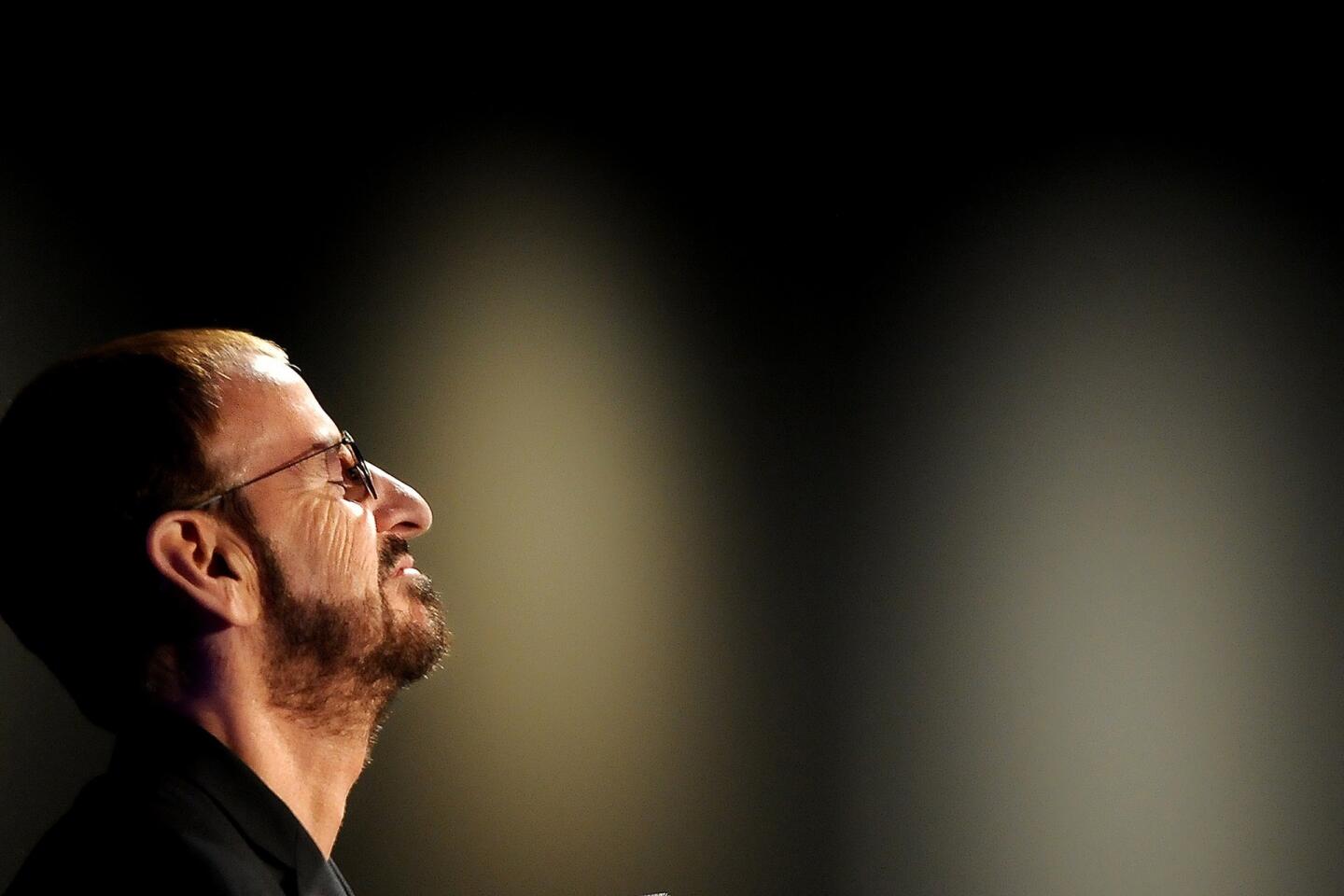

The marketing of AMC’s new drama, “Low Winter Sun,” revolves around a moody black-and-white photo of lead actor Mark Strong and the show’s tagline: “Good Man. Cop. Killer.”

Just another player in the crowded genre of “Gee, it’s tough to be a straight white man.” Or, as it has come to be known, “prestige television.”

FOR THE RECORD:

Antihero on TV: An Aug. 18 Critic’s Notebook about the tyranny of the antihero on television said that the series “Top of the Lake” was on IFC. It was on Sundance Channel. —

The blooming of high-quality serialized fiction on television has hit critical mass, luring writers, directors and stars from the screen formerly known as big and generally driving cocktail and cultural conversation in every medium and demographic. (Sundance recently debuted “The Writers’ Room,” a television show about making television shows, which is more than a little snake-eats-tail alarming.) TV is the new quiche, the new black, the new hit single.

INTERACTIVE: Fall 2013 TV preview

Yet even as the tone, structure and delivery system of the medium diversify, the industry definition of Good Television, as in important, award-winning television, remains infuriatingly narrow. Drama trumps comedy, male trumps female, most everyone is white and someone needs to get killed or commit adultery by the second scene at least.

Thankfully, glimmers of change flicker here and there. Comedies such as “Louie” and “Orange Is the New Black” are increasingly acknowledged as being art as well as entertainment, the power-soap appeal of “Scandal” is gaining critical admirers along with Twitter followers, while the mad buoyancy of “Bates Motel” offers a bridge between the cynicism of cable and the guarded romanticism of broadcast networks.

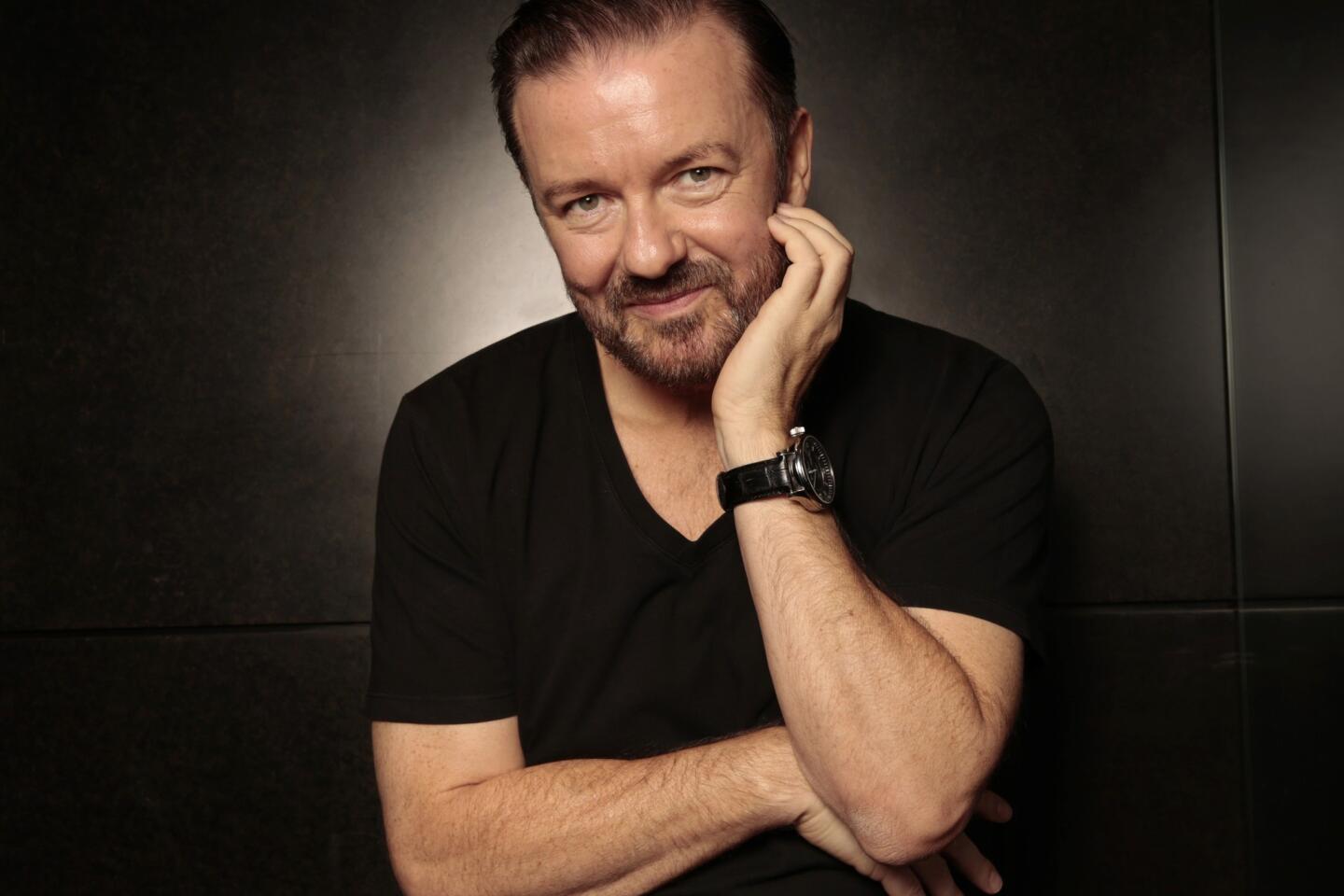

Still, most dramas striving for A-list credibility (and some that aren’t) inevitably revolve around a driven yet unhappy male lead suffering from illness/dysfunction plagued by a moral ambiguity born of a troubled history and the lonely void all that entails.

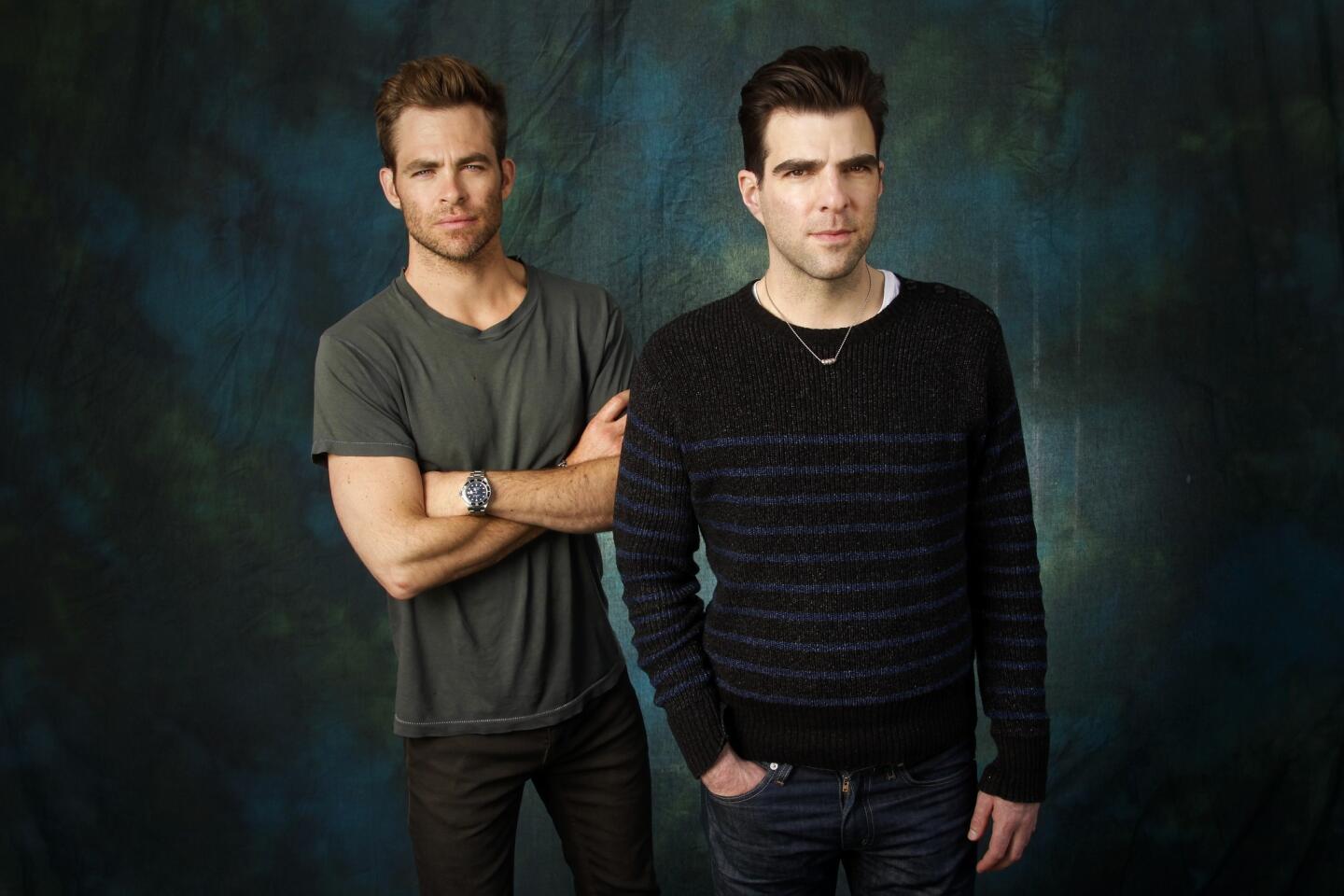

It’s “Mad Men’s” opening credits of a man falling through space, it’s Walter White’s more literal descent into darkness on “Breaking Bad.” It’s the essential goodness but self-loathing eyes of Peter Dinklage’s Tyrion Lannister (“Game of Thrones”) and Andrew Lincoln’s Rick Grimes (“The Walking Dead”). It’s the black humor of Timothy Olyphant’s Raylan Givens (“Justified”) and Kevin Spacey’s Francis Underwood (“House of Cards”), the self-righteous moral dexterity of Michael C. Hall’s “Dexter,” Steve Buscemi’s Nucky Thompson (“Boardwalk Empire”) and the entire cast of “Sons of Anarchy.” It’s even the psycho-sadomasochistic relationships that drew Kevin Bacon (“The Following”) and Hugh Dancy (“Hannibal”) to TV.

And now it’s Strong’s killer cop (seen previously, it must be added, in a British version of the show) with a tear rolling down his face.

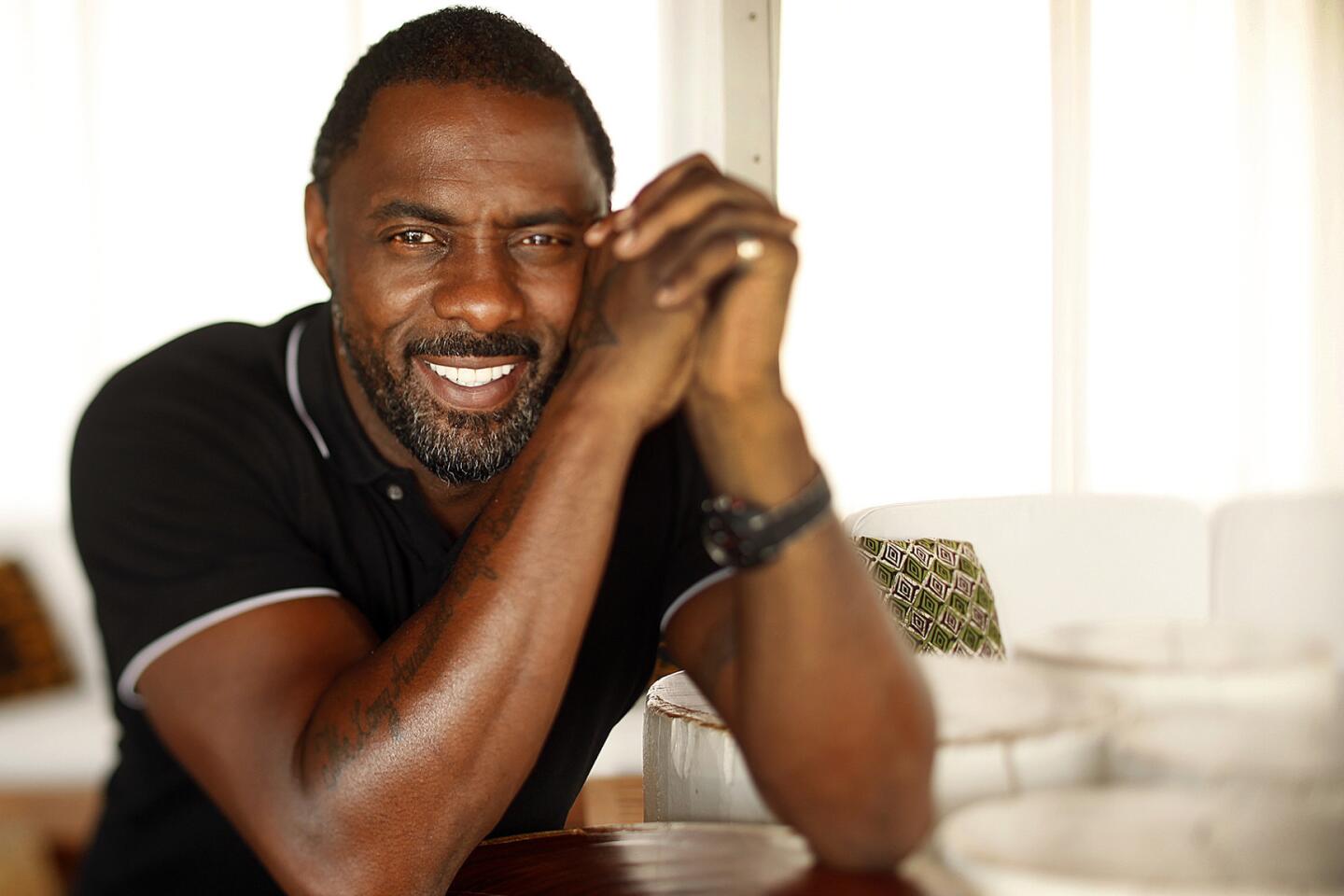

The appeal of such characters is obvious — male viewers identify with the inevitable midlife frustrations writ large and female viewers want to save them (it helps that the actors playing these guys are usually pretty attractive). Less appealing is their tyrannical hold on the gold standard. When did the problematic protagonist become the necessary ingredient for dramatic excellence?

GRAPHIC - ‘Breaking Bad’ to ‘Justified’: Killing off your favorite stars

The short answer is the day David Chase brought Tony Soprano into the world. The long answer is when “Moby-Dick” began topping all those “greatest American novel” lists.

Many forces have contributed to the renaissance of television but none more than HBO’s decision to get into the original content business. “Sex and the City” was premium cable’s first hit, a show that launched a thousand voice-overs and the post-feminist female — candid, ambitious, sexually adventuresome but still lovable — who would quickly infiltrate traditional broadcast TV. Without “Sex and the City,” it’s difficult to imagine the prolific and influential career of Shonda Rhimes.

But the pedigree of HBO, and eventually television itself, rose on the shoulders of the antihero — the torn, angry and often ill-shaven fellow waving a gun and/or a bottle around, troubled, oh, so troubled but still smarter than anyone else in the room. “Oz,” “The Sopranos,” “The Wire” quickly spread their grim world view far and wide; for years, Hugh Laurie’s damaged doctor on “House” was the only recurrent broadcast star in his Emmy category.

PHOTOS: Families that changed TV

This year, of the Emmy’s six drama contenders, only “Downton Abbey” (which has a rich vein of “pity the poor rich white folk” running through it) does not fit the broken-white-guy-breaking-things template. “Homeland” has a female co-lead but meets all the other requirements — mental illness, moral ambiguity, gun — quite nicely.

Success inevitably breeds imitation, so not surprisingly any network entering the high-end original programming business these days does so with similarly themed shows: “Copper” on BBC America; “Hatfields & McCoy” and then “Vikings” on History; “Rectify” on Sundance; the upcoming “Klondike” on Discovery.

And Chase certainly didn’t invent the antihero. American literature is littered with men in varying states of fracture, from the hypocritical Arthur Dimmesdale (“The Scarlet Letter”) and “Moby-Dick’s” obsessive Ahab to Bret Easton Ellis’ “American Psycho.” Much modern fiction lauds moral ambiguity as a sign of intelligence, the damaged lead as the true Everyman. Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Updike, Mailer, Faulkner and Styron battled evil and banality in equal measure, their characters wounded and wounding warriors of the existential age. Tales that dealt with other themes might be good, but there was only one Great Story: Man versus Himself in a callous and confusing new world.

At this summer’s TV critics meetings, there was talk about the high testosterone count of prestige shows. HBO’s Michael Lombardo was asked why there weren’t more female-centric dramas, while Chris Albrecht touted the new period miniseries “The White Queen” as a chance for Starz to court “an underserved audience.”

PHOTOS: Dysfunctional TV famalies

Never mind the rather insulting and wrong-headed insinuation that only women would benefit from more diverse lead characters, the real issue is not so much better serving the female audience — women love Dexter and Don Draper as much as the next guy — as it is broadening the definition of Important Story. The reliance on violence and vice to establish a show as deep and fearless all but requires male leads; with the exception of, perhaps, Patty Hewes on “Damages,” women on television still cannot get away with murder.

Female leads, or so conventional wisdom tells us, can be complicated but they must be likable. The recent American remake of “Prime Suspect” softened the British antiheroine Jane Tennison to the point that she wore a kicky hat (and sank like a stone), while the bipolar reactions to HBO’s “Girls” (It’s the Holy Grail! It’s sexist propaganda!) illustrate just what happens when this particular world order is even questioned.

PHOTOS: Hollywood Backlot moments

Sundance Channel took baby steps away from the haunted hero model last year with Jane Campion’s “Top of the Lake.” Though bearing certain hallmarks of the Prestige in a Box (cops, dirt, violence against women), the show revolved around a woman with a more open-ended sensibility and often wandered into an amusing and insightful B-plot about a group of women literally fleeing the world of men. And though the latest antihero offerings — Showtime’s “Ray Donovan” and “Low Winter Sun” — met with much ennui, comedies including “Girls,” “Veep,” “Nurse Jackie,” “Enlightened” and most recently “Orange Is the New Black,” have begun generating the sort of awards nominations and critical buzz previously reserved for dramas.

Along with a few police procedurals, these dark, almost borderline unfunny comedies have become the female equivalent of Important Television. Good shows, some even great shows, but not granted the same social respect as their dramatic peers. Which is why Netflix opened its original content gambit with “House of Cards” and slid out “Orange Is the New Black” with relatively little fanfare during the summer; not surprisingly, “House of Cards” dutifully scooped up an armful of Emmy nominations.

“Orange Is the New Black,” however, may change the world. Or at least help end the tyranny of the self-absorbed antihero.

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

Jenji Kohan’s adaptation of Piper Kerman’s tale of serving time in a women’s prison is an epic of a whole different stripe. On one level it is the female equivalent of “Oz,” comedic where “Oz” was grim, focused on the delicate piecework of negotiation rather than the blinding fear of power.

It all requires the most auspicious cavalcade of socially, economically, sexually and racially diverse female characters ever seen on any screen, and none of them are lovable in the traditional sense. Prison has stripped them of their accessories, both literal and narrative; a premium is put on action, on ability rather than personality. “Orange Is the New Black” proves that women don’t have to be likable or sexually alluring or deliciously catty to hold our interest, that multi-faceted female angst and enlightenment are just as compelling as the male variety.

“Orange Is the New Black” proves that the Second Wave of televisionism is upon us. It may remain hard to be a straight white guy in today’s big bad world, but prestige, like suffrage, needs to become universal.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.