Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

A handsome man with the physique of the college football player he had once been walks into an airtight, 8-foot-square Plexiglas booth heated to 90 degrees.

The door closes behind him.

When he staggers out, two hours later, he has won no fabulous prizes. Instead, he is a little headachey. He has trouble concentrating, his eyes are weepy, and, as a doctor will soon tell him, he has lost — temporarily at least — 22% of his lung capacity.

By now, you know this man is not a game-show contestant. And this is most definitely not a game.

But it is a stunt.

The newspaper reporters and photographers were there in 1956 to watch the man in the box, S. Smith Griswold, head of Los Angeles County’s 9-year-old Air Pollution Control District. And he had a point to prove.

He spent those two hours breathing in a potent summertime version of what millions of his fellow Angelenos were breathing every day — smog — to show them what it did to the human body, and to Los Angeles.

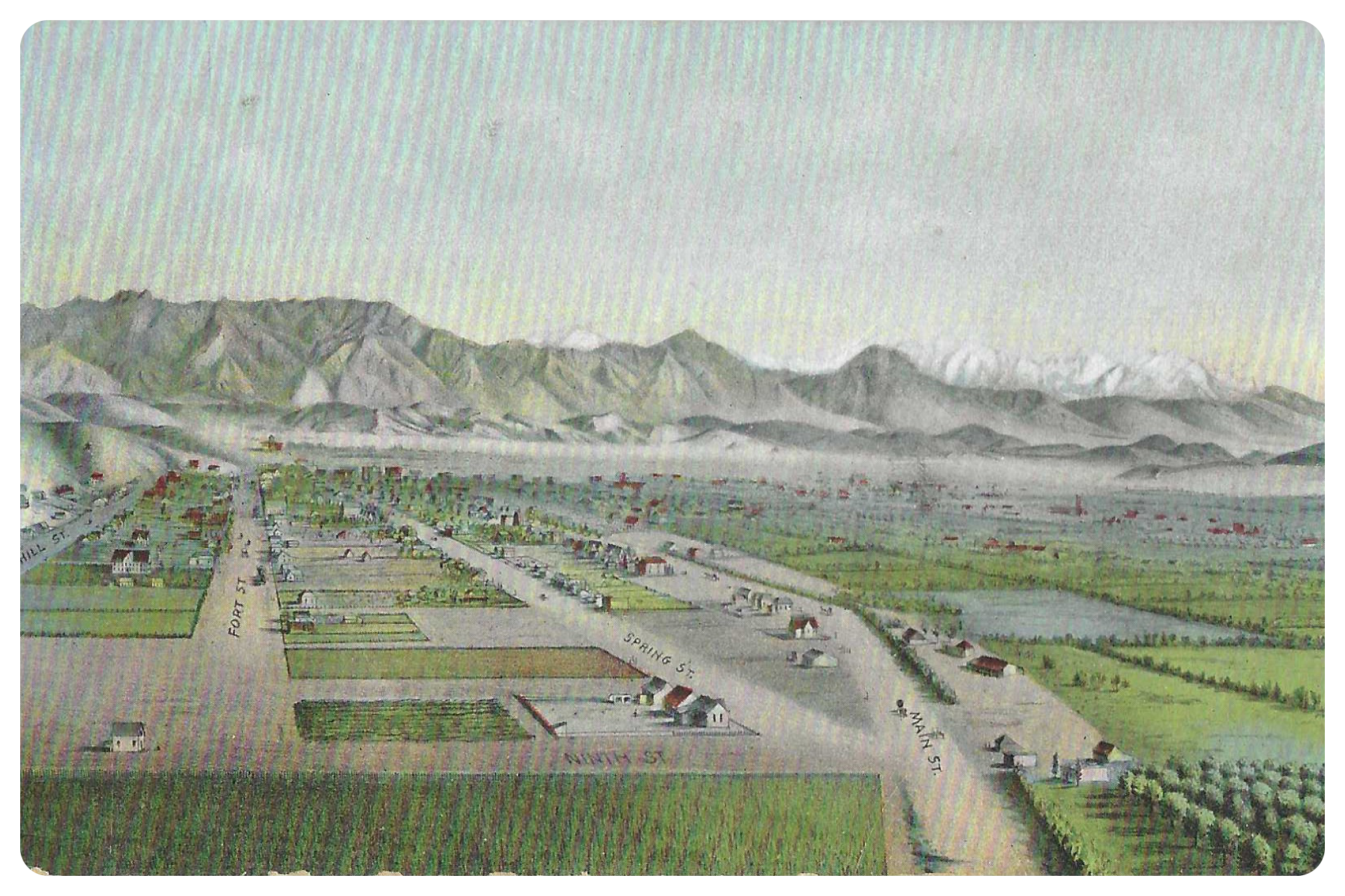

L.A. was like the royal baby in a fairy tale, endowed with abundant gifts — glittering sunlight, dramatic landscapes and lovely beaches that remain untarnished — until the bad wizard shows up with the asterisk:

“Yes, your landscape is gorgeous, but that magnificent rim of mountains will trap the stew of air inside your basin as surely as a lid on a cookpot. And those glittering sunbeams will curse you by creating a doomsday photochemical reaction with whatever you put into that photogenic bowl — smoke, car exhaust, wafting industrial toxins — so in time you won’t even be able to see those glorious mountains.”

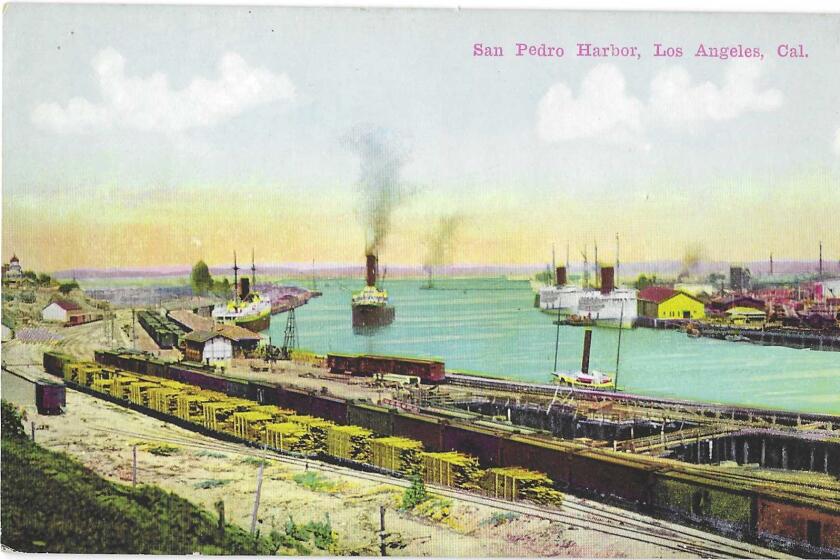

When you think about it, it doesn’t make much sense for 1890s L.A. to put its port all the way in San Pedro. This is the story of how that came to be — and not the competing alternative, Santa Monica.

The first thoroughly documented smog attack in Los Angeles was July 26, 1943. People gasped and wept and reeled. The air stank and tasted of bleach. You couldn’t see to the end of your street.

Gas masks that people had bought in anticipation of an enemy invasion were put to use — the United States was, after all, a combatant in World War II. But the bad air wasn’t the result of an enemy chemical attack. A day later the most obvious source of the muck turned out to be a nasty chemical byproduct from a plant making artificial rubber for the war effort.

The plant was briefly closed down, but the smog kept coming. It was turning into one of those murder mysteries where the identity of the killers seems so obvious at first, and so wrong in the end.

In the 80 years since, we have rehabilitated some of those killers, and locked some of them up. Others, we have put quietly to death. But some are still out there, still committing mayhem on our landscapes and our lives.

Four hundred and one years earlier, the first “smog report” was entered into the log of the San Salvador, a galleon captained by the Iberian Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo. He and his crew were the first Europeans to lay eyes on California, and what they saw on Oct. 8, 1542, off the coast of what is now Los Angeles, was ... proto-smog.

The same lid-on-a-pot geography of World War II was in place in the 16th century, when, from offshore, Cabrillo’s pilot spotted the chocolatey layer of smoke inland, either from a natural seasonal brush fire, or from fires started by Native Americans to drive game. In the ship’s log, the place was named “Bahia de los Fumos.” Bay of Smokes. The next day, the departing ship’s log elaborated: “Bay of Fires.”

Angelenos in the centuries thereafter came to know something about this very occasional quirk of air and topography and seasons. But it wasn’t until the war brought the defense industry, and the defense industry brought people by the many thousands, and the people bought and brought their cars, that — like tumblers falling into place on a lock — all the ingredients for smog fell dangerously into place.

Putting up with smog for the duration of the war was one thing, with all the defense plants going full blast. But V-E Day and V-J Day came and went — and the smog didn’t.

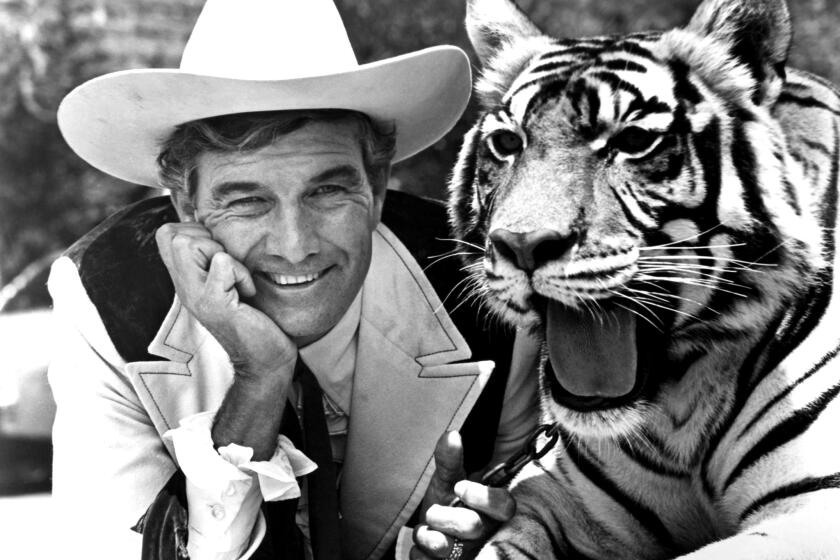

Cal Worthington (and his ‘dog’ Spot), ‘Madman’ Muntz and other colorful local pitchmen used to claim space in the public consciousness. Our culture may no longer be built for that brand of commercial antics.

In 1947, L.A. County created the Air Pollution Control District, granddaddy to today’s South Coast Air Quality Management District, to hunt down the guilty parties. It was empowered to switch on the wartime air raid sirens to signal Angelenos when the air became too horrible to remain outside.

All of the big industries, the defense businesses that stayed in business, the new peacetime factories, and the construction and manufacturing interests — almost all of them were required to get permits. But this was a porous arrangement. In 1970, companies filed 337 petitions for waivers from complying with pollution rules. Only 19 were denied.

And the smog persisted.

A beauty contest to select Miss Grand Central Air Terminal 1947 in Glendale wound up with only 10 contestants. The other 20, flying in from across Southern California, couldn’t get there because their planes couldn’t land in the smog. A year later, during a court hearing about the pollution generated from a dump in Whittier, the judge was startled to see that “the smog comes right into the courtroom and envelops the witness box.”

Los Angeles — the place where people with tuberculosis and emphysema had come by the thousands for a remedy (or a stay of their death sentence), the place that boasted that its very air could cure people — was now creating its own lung cases.

The smog alarm didn’t begin in earnest with people.

It began with plants.

In the 40 years before 1950, Los Angeles was consistently the single most productive agricultural county in the nation. Quantity, quality, variety — green on the ground and green on the trees meant green in the pockets.

But the demand for houses for all those new postwar Californians was not the only factor that was costing L.A. County its agricultural riches. Smog got there first.

By the war’s end, it was noticeable. Beets, spinach, and endive died where they grew, with telltale dried-up, silver-metallic leaves. In 1949, “smog gas” killed a field of romaine lettuce in 36 hours. Growers around present-day Compton and in the San Gabriel Valley took a chemical company to court for killing their crops. An Inglewood orchid grower — L.A. was once a flower powerhouse — said smog had wiped out most of his blooms in 1958; out of 3,000 plants, he could save only two dozen.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

And so the conflict was set: newer industrial businesses versus the older agricultural business and human health.

The institutional response was that burdening businesses with smog regulations would be too costly.

At one of many smog summits — this one convened by a county supervisor in 1949 — a weather forecaster named Irving P. Krick came down squarely, and rather fatalistically, on the side of industry. For 40 or 50 days each year, temperatures reached smog-critical levels, but even shutting down refineries during the worst smog days would be “a totally useless cost.” Angelenos, Krick argued, “can’t have their cake and eat it too ... smog will be a continuing problem and we may as well learn to live with it until we can know all sources that produce it. There are still more benefits derived from living in Southern California with smog than in living elsewhere without it.”

It took the medical experts a while to get up to speed, to organize any methodical surveys of what smog does to a human body. And anyway, how could you separate out smog damage, from, say, the effects of smoking, when almost half of all American adults were nicotine freaks? “Research on the problem is extremely complex,” is all the state’s public health director could offer an Assembly committee in 1950.

Ed Avol, an L.A. native whose school days were marked with all the times that kids were kept indoors during recess because of smog alerts, became a professor of clinical preventive medicine at USC’s Keck medical school and an expert in environmental health. He’s been at it for more than 30 years.

Today, “we know a tremendous amount about the effects of air pollution, both short-term and long-term effects on people,” Avol told me in 2019.

“Certainly the lung is the primary organ for which there are effects, and we know a lot about it. But it goes far beyond the lungs, because once it crosses the air-blood barrier in the lungs, it gets into the blood in the circulatory system and then essentially the contaminants could go anywhere in your body.

“So it’s not surprising that we see effects in the lungs, in the heart, in the metabolic system, in the brain. ... It’s actually been connected with some neurological problems in terms of younger children being able to pay attention and learn in school. ... Later on in life it turns out that air pollution has a role to play in terms of thinking about Alzheimer’s and dementia and the rate of neurological decline.”

For the first Earth Day, in April 1970, the comic-strip artist Walt Kelly came up with a poster with the legend, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

No ordinary car-obsessed Angelenos wanted to hear that. Big industries had to be responsible for smog, right? We’re the victims here! The oil wells and refineries, the smokestack companies, the metal and chemical shops, the aviation and defense plants — what else could be at fault?

The bearer of the bad news was the Caltech chemist Ari Haagen-Smit. He began his smog research in 1948 — a year of wretched smog attacks, and the year his wife shared hostess duties when L.A.’s first smog czar addressed Caltech’s faculty women’s club. (Maybe she shared what she heard with her husband and that started him down his research path.)

Four years later, he was ready with his results. The “birth of smog” has been discovered, The Times crowed — an “astounding phenomenon.” When car exhaust and refinery hydrocarbons, which we had aplenty, are bombarded by sunbeams — voila! — we get ozone, a principal ingredient in smog. The Times described Haagen-Smit’s announcement melodramatically. “Going on in the air, under the effect of sunlight, are billions of miniature ‘atom bomb’ explosions, a chain reaction of violence and chemical fury.”

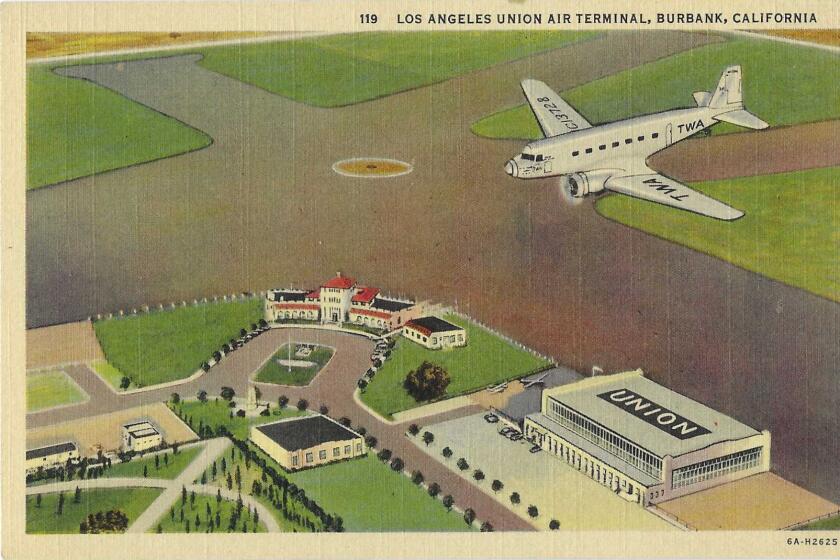

We still have lots of airfields, but gone from the landscape are the runways — near Griffith Park, near Wilshire and Western, in the Palisades — that could have challenged LAX for air superiority.

Another chain reaction of fury? Angelenos, when they were told that their cherished cars — and their drivers — were the problem.

Griswold of the Air Pollution Control District suggested carpooling and floated the idea of reviving wartime-style gas rationing. Imagine how popular that was to the hot-rodders and cruisers and suburban commuters who gloried in being two- or three-car households.

Griswold was less inclined to blame cars and drivers than car manufacturers, who had the technology, he said, to control tailpipe crud, and there were patent records from 1909 to prove it.

They were just playing the odds, Griswold contended. While L.A.’s smog cost us $11 billion a year, automakers had spent “less than one year’s salary of 22 of their executives” to clean up a problem much of their making, he was quoted as saying in his New York Times obituary. And as some stationary sources like factories got cleaner, those gains were soon overtaken and overwhelmed by more and yet more cars on Southern California asphalt.

Angelenos were also in the habit of burning up their household garbage in backyard incinerators. So handy. So filthy.

In 1957, L.A. County banned the incinerators outright, in favor of curbside trash collection. But some Angelenos took their picket signs and their dudgeon to City Hall. Curbside collection? Expensive! Burdensome! Practically un-American!

Into the 1960s, L.A. mayor Sam Yorty courted votes from a “housewives revolt” over the oh-so-taxing chore of separating glass, metal and paper rubbish.

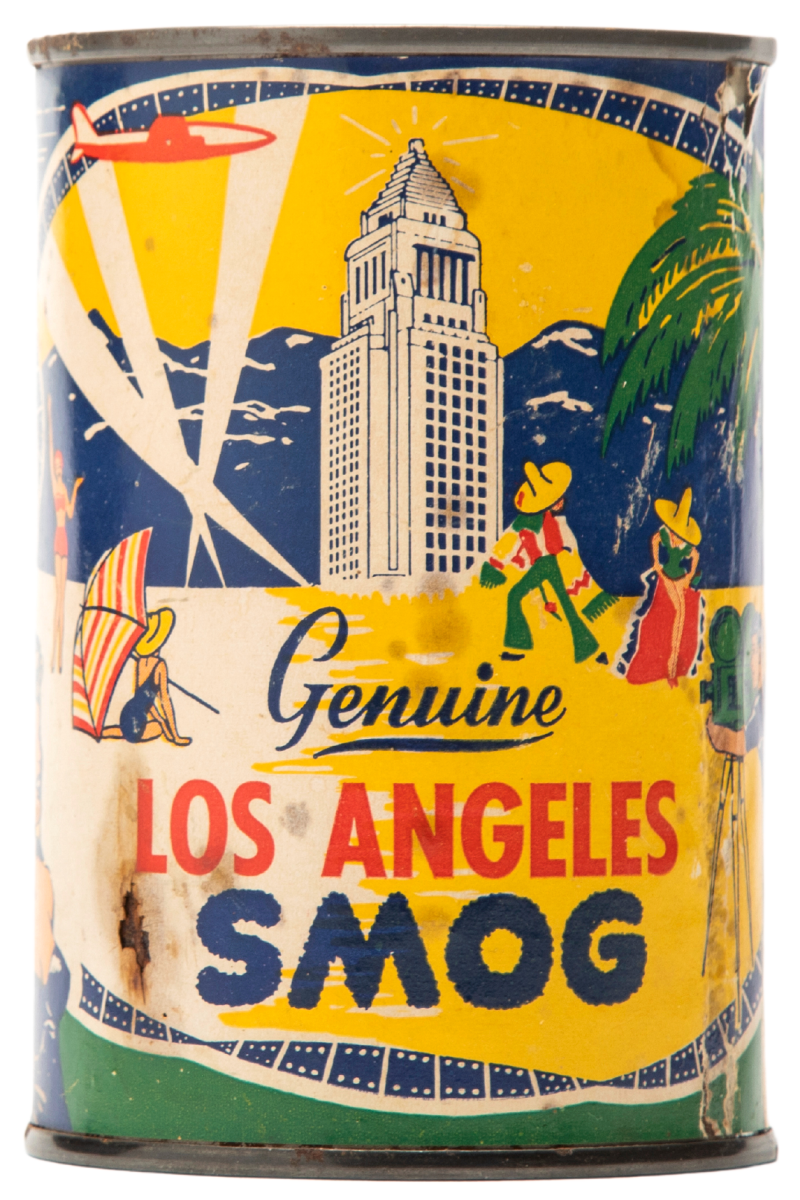

When we weren’t cursing the brown darkness, we did sometimes manage to make light of it. Late-night host Johnny Carson made our smog famous — a national punchline. I found that there was smog memorabilia to be collected, and so I did, like a smog crying towel, and “genuine” canned L.A. smog — “Breathe the air the movie stars breathe!” was the promise on one Technicolor label.

A 1950s souvenir smog can, from Patt Morrison’s collection, promises that it contains “the smog used by famous Hollywood stars!” with “no pollutants or irritants removed!” (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

A Los Angeles physician named Elmer Belt, a member of the state Board of Health, said a patient of his, a man with one glass eye, had a bloodshot version made when he came to L.A.

Way back in 1944, a body called the County Fumes and Smoke Commission more or less knew the answers. It just couldn’t show its work; Haagen-Smit would do that years later. Here is how it so presciently described L.A., one year after the notorious 1943 wartime smog attack.

“A community of more than 2,000,000 people is shut up in a vast room with doors and windows closed and into this room is poured the smoke and fumes from a thousand stacks, from tens of thousands of home incinerators, from hundreds of thousands of autos and trucks, poisonous vapors from chemical plants, stenches from packinghouses, sewers, and glue factories, lachrymating gases from refineries and burning rubbish heaps — a hellish cloud that fills the room and is indifferent to municipal boundaries.” (I love “lachrymating” — such a high-flown word for something that triggers weeping.)

That was almost 80 years ago. The diagnosis was right. Since then Los Angeles, and California, joined by much of the rest of the urbanized world, are engaged in the same battles.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

There is no smog cure — the ancient geography sees to that — but there are treatments. Like the water-savings devices that make it possible for more Angelenos to use less water, many passive and more or less painless new technologies, like electric and hybrid cars, fueled by kilowatts or by cleaner (and more expensive) special formula gasoline, have made the air noticeably better.

Yet 98 out of 100 Californians still breathe unhealthful air.

And smog is a borderless phenomenon. Chip Jacobs, who co-authored the seminal book “Smogtown: The Lung-Burning History of Pollution in Los Angeles,” says with a sad shake of his head that a regular Pacific Drift of pollution from China accounts for a good share of air pollution for the Sacramento Valley and Bay Area. “So even as our cars have gotten cleaner, our gasoline is purer, and we’ve taken all these technological steps, this Frankenstein that we helped create known as the People’s Republic of China’s economy is biting us.”

Cleaner air, but not clean. Don’t be fooled — the noxious stuff that goes by the name of tropospheric ozone is the smog we can’t see. Still, on most days now, we can awaken to the sight of mountains. Schoolkids can play outdoors at recess. And if your eyes water, it’s likely at the sad state of the world, not the stinging state of the air.

And, again, like in the fairy stories, after all the ugly, choking poisons we are cursed with, our garage-sale jumble of icky particles — from coal, chemicals, cars and their noxious human-made brethren — still does leave behind one speck of a blessing: killer sunsets.