When the pandemic hit, 26 new city homeless shelters opened. Only seven are left

As the summer heat crested in the late afternoon Monday, Royal Fahrner left the Pan Pacific Park recreation center with a large plastic bag and her backpack.

A long bus ride downtown to a storage facility was in her future. The rec-center-turned-homeless-shelter, where she had been staying for several months, was scheduled to close Tuesday. So she was getting ready to move to the Westwood Recreation Center along with 42 other people.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, she has shuttled among several shelters in Los Angeles city recreation centers. Some legal trouble meant she couldn’t leave the county, and since she had nowhere else to stay, Fahrner said these shelters had been a lifeline — and a salvation from staying on the streets.

“It’s surprising. Everyone thinks it’s going to be terrible, but it’s been pretty great,” she said through a yellow mask with a tongue sticking out on it. “The community has been really nice.”

After The Times began inquiring about why this shelter was closing, a spokesman for Mayor Eric Garcetti, Alex Comisar, said the city had reversed course, and it would remain open.

Still as temperatures reach record levels in California, activists and homeless Angelenos are wondering why more Park Department gyms and recreation centers aren’t being used to get people off the streets. When the pandemic began earlier this year, the city quickly opened up more than two dozen of these facilities to homeless people as it worked with the county to lease hotel rooms through a statewide program, Project Roomkey.

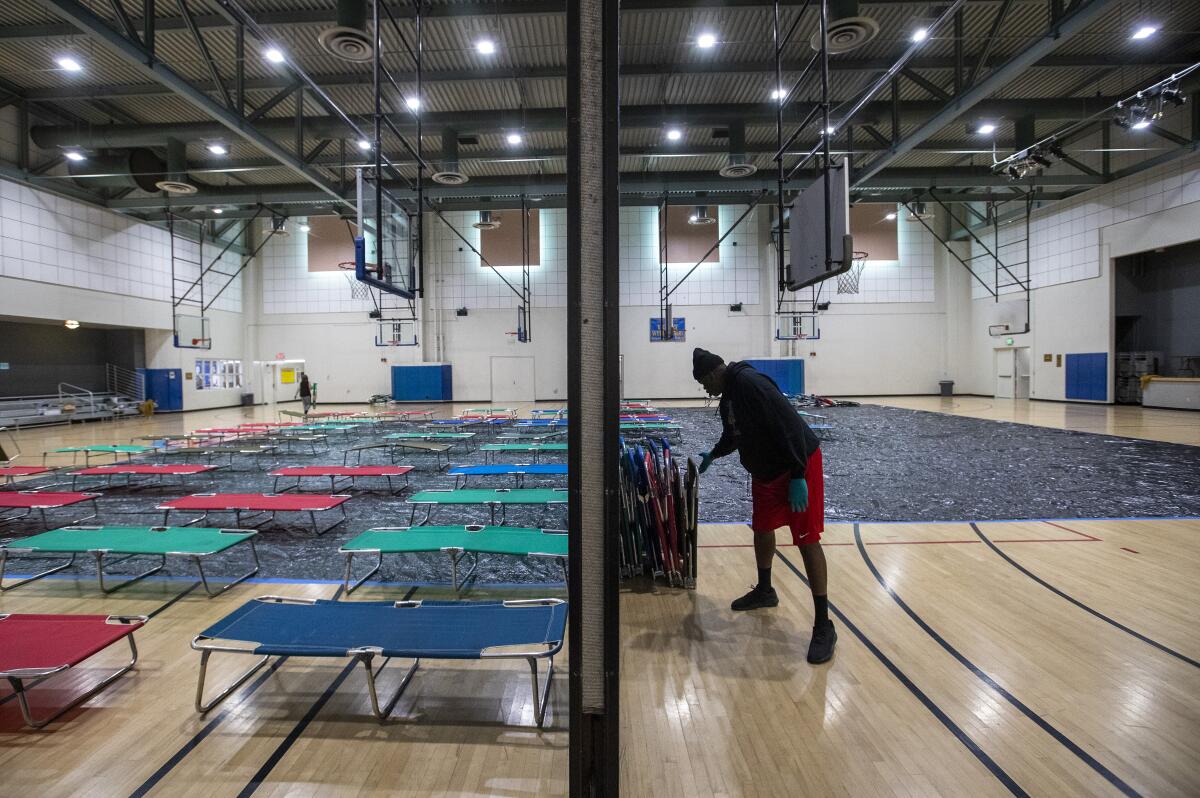

Garcetti said this effort would shelter as many as 6,000 people but at its peak in mid-May, when there were 26 parks and recreation facilities being used, their total sleeping capacity was only about 1,000, according to data provided to an L.A. City Council office and shared with The Times. On May 13, 860 of the beds were occupied.

Now there are just seven sites open, including the Pan Pacific Park location, with a total of 166 available beds. About 140 beds are occupied. Local activists say the closures came too early, when the need for emergency shelter is still great.

“We are in the middle of a viral pandemic,” said Emily Kantrim of the Midtown Los Angeles Homeless Coalition. “This pulls people away from the medical care and support they were getting. “

On May 12, these shelters stopped taking new admissions, according to Los Angeles Homeless Services Agency (LAHSA) Executive Director Heidi Marston. The city had previously said that it wanted to return these facilities to their original use by September.

An ambitious Los Angeles County plan to lease hotel and motel rooms for 15,000 medically vulnerable homeless people is falling far short of its goal and may never provide rooms for more than a third of the intended population.

Marston said her team has been working with service providers to get people staying in these sites into permanent housing or into hotel rooms through Project Roomkey.

“The response [from the mayor’s office] that we have received is that these were always intended to be temporary programs, so let’s start to sunset them and let’s also do everything we can to be compliant with public health guidance,” Marston said.

Comisar, the Garcetti spokesman, said: “We’re consolidating sites and resources to make it easier for LAHSA and service providers to prioritize placements in longer-term shelter and housing.”

At first, Marston said there was a lot of concern about moving people into congregate settings like this and there have been coronavirus outbreaks in several of the shelters. Since it opened, there have been eight confirmed cases of COVID-19 among the Pan Pacific Park shelter’s staff and residents. There have been no deaths.

Joseph Manko and a friend who offered only his initials, N.N., sat on a park bench outside the shelter in the shade smoking cigarettes and chatting. They both have been here since April and, within weeks of arriving, were forced to stay inside and isolate after a resident tested positive.

Manko, who had a stroke that left him struggling to use his left hand, had been living in a hotel but quickly ran out of money. The bills for his healthcare piled up, and he moved into this shelter.

Manko and N.N. said the staff had been very attentive and caring during a tough time.

“They handled it well,” N.N. said.

Marston said concerns about social distancing remain, but it would still be useful to have the recreation sites open because it would mean fewer people on the streets. At the beginning, the city and county and LAHSA were trying to build up a larger capacity of hotel rooms available. Now that that’s in place, even though it’s less than desired, she said it would still be good to keep these facilities available.

“Any option that we can have to offer folks is a valuable one as long as we’re maintaining social distancing,” Marston said.

Amid a brutal heat wave, with temperatures in downtown Los Angeles hovering near 100 degrees, six of the recreation centers have been turned into cooling centers for people who had no place to beat the heat. But Genevieve Liang, a board member of the SELAH Neighborhood Homeless Coalition, which serves seven neighborhoods northeast of downtown, said the number of cooling centers is woefully inadequate and that the public has had to step up by making sandwiches and bringing ice water for people on the streets.

“Where is the infrastructure the city is supposed to provide? There is a lack of capacity and planning. And where are these folks going to go?”

Local outreach workers and activists such as Liang said that they felt in the dark about why these facilities had been closing as shelters and left to worry where homeless people would end up.

A judge ordered officials to provide space in shelters or alternative housing for homeless residents living near freeways. But where will they go?

“The only thing we heard early on was [Deputy Mayor for Homelessness] Christina Miller said the recreation centers have to go back to their original use,” said Kantrim, noting that a large encampment sprang up around the corner when the Hollywood Recreation Center on Cole Avenue shut down. Miller recently announced her resignation, effective at the end of the month.

Kantrim said the use of this facility had been successful. Giving homeless people the opportunity to stay indoors allowed them to stabilize and clean up after the trauma of the street, she said.

“There is no reason for it to go. There is no answer from our elected officials about what is the strategy,” she said.

Arnali Ray, chief of strategy and programs officer at the Saban Community Clinic, said her agency has been going into Pan Pacific Park to link people staying there to medical care — and that often started with a shower and some food.

“They’re hungry, thirsty and dehydrated. It’s not great during a pandemic to be unhealthy,” she said. “We’ve been going around in circles, not sure who has the plan, what is the plan? It seems to me no one has an answer, which leads me to believe there is no real plan. What is the rush to get the recreation and park centers back?”

Back in the park, a man staying in the shelter sat in the shade cleaning out a pipe and waiting for his friend to return with cigarettes. He declined to give his name but said he had been staying on the streets in South Los Angeles before this. The shelter was safe and secure, he said, because the police kept a close eye and there were a nurse and staffers from the Department of Mental Health on site.

For him, it was no surprise the shelter would be closing soon.

“Rich people want their park back,” he said. “You can’t blame them for that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.