This story is part of “Discourse,” a fresh look at the dire state of the bicoastal conversation — free from corniness and cliches. Check out the whole issue — the “New York” issue, if you’re reading between the lines — here.

My friendship with Fred Moten spans a nation of Black music. Black improvised music and poetry are the safest refuge for agape love in the West. Amiri Baraka’s classic manifesto as book, “Black Music,” testifies to this expansiveness. Some of us are lucky enough to find friendship in the spectral echoes of divine listening.

There are shared associations that haunt both Fred and me. We both love Amiri, we both love Black music. We repeat our devotions and remix them as lifestyle. We promise poems. We know the Tricky song that repeats “you promised me poems, you promised me poems,” and we know the friendships between instrumentalists that function like poems until June Tyson and Sun Ra are composing tone poetry in what Fred calls “ensemble time” live, onstage. We witness them through the ages as the great Black simulacra of our never-returned 40 acres, our justice, our collective, agape love transmitted as music.

We’re asked, what are the different experiences of jazz on each coast, in New York, in Los Angeles? We must understand that the music of collective improvisation mirrors the relationships in your life and your relationship to your own many-layered consciousness, wherever you encounter that music. How do those relations change from city to city? How do they go underground in the South and come back up panting and bebop in Manhattan, and unwind again in Los Angeles, becoming too cool? Or unravel into the score of unwritten cinema on empty, late-night roads where you go on a drive just to listen to an album with your friends? Leaning into that desolation, you find the best company/music.

You cannot beg a god for forgiveness, but you can be ready when he hints at offering it after a long standoff.

When Fred lived in L.A. and I still lived in New York, he picked me up once from an apartment I had sublet in L.A. for the winter break and brought me to his house for dinner with his family, all so we could listen to some music, really. He introduced me to Arthur Jafa, and they talked about Al Green and the way his sound saturates and soothes beyond measure. Not long after that, Amiri Baraka died. We were both in L.A. and not Newark for the funeral, and so I wrote a jazz club here called Blue Whale and organized an impromptu Baraka memorial. Local poets and admirers gathered, and we read his poems and tried our best to access the spirit of a fallen hero of ours. There is a devastating earnestness that stains that kind of effort with unspeakable beauty, the kind that almost feels like shame for its own reverence. You almost never want to bring it up again.

We should mention Charles Mingus, born in Nogales, Ariz., but raised in Watts, Los Angeles.

He grew up with Eric Dolphy. Mingus played the bass and Dolphy puppeted and palpitated the wind on alto saxophone and flute. They were both casual wizards whose combined beauty is heartbreaking as an ensemble — too perfect to endure without being haunted and ephemeral. Their agape love is evident everywhere but especially in Mingus’ elegy, “So Long, Eric.” He maintains his West Coast casual in the title, which marks his long goodbye to his friend, who died in June 1964 at the height of his powers. Mingus had a premonition during a rehearsal in Europe in the spring of 1964 and asked Dolphy, “how long are you staying out here? When are you coming home?” I imagine this as their final exchange and let it reverberate like a broken promise among telepaths. A gaping agape prayer.

Fred and I were both raised on the West Coast with Southern roots. Fred in Las Vegas by way of Arkansas, and me in Los Angeles with a father from the Mississippi Delta. As a kid, I’d gone back and forth to Vegas dozens of times for dance competitions. There is a shared psychic landscape between Fred and me that turns up as poetics that needs to shred like free jazz but with the will of the blues “and proceed to move the crowd like an old Negro spiritual,” as rapper MF Doom once outlined as method.

In the 1950s, he quickly developed a reputation for being a gun-toting, switchblade-carrying man on one hand and an impossibly tender soul who could write love songs with the facility of angels on the other.

When I first met Fred, I went to a big party at his house after a conference he’d invited me to at Duke. I remember him flaunting his bass proudly and maybe playing it some while we read poetry in a round. Agape freedom jazz in the undercommons. I went back to the hotel and listened to Mingus until sunrise. “Haitian Fight Song,” “Myself When I’m Real,” “Adagio ma non Troppo.”

At the time, I was living in New York. I had met that mutual hero of ours, Amiri Baraka, a couple of years earlier, at a show at Blue Note, and he’d taken me under a little region of his vast wing. I was in graduate school and I’d written to Ben Ratliff, the New York Times’ jazz journalist and now a good friend, and asked if I could apprentice with him for a while on assignments. He said yes and thus began my era of going to show after show, seeing every jazz musician playing in New York at that time, from Jason Moran to Cecil Taylor to Esperanza to everyone, everywhere, straying from the academy for the club, as one does, or should. I became double and triple apprentice of the ineffable poetics of sight-sound.

“New York Is Now!” is the title of an album by saxophonist Ornette Coleman. I bought a shirt with that album logo on it, though I don’t believe in any such callow regionalism as one or the other coastal city winning a culture war. My ethic is more aligned with a different Ornette album, “Beauty Is a Rare Thing.” Ornette is from Fort Worth, Texas, and spent some time in L.A. too. I think he was a mail carrier here. A postman. Supernatural man. He declares and appropriates New York as armor and muse almost involuntarily. Sometimes his sound is so far out people take him into the alley and beat him up after sets in this New York he claims is the moment, the gestalt, the threat. Maybe that violence is part of it, a catastrophic ammunition for what he calls “harmolodics,” his new way of playing, a Jean Toomer-esque sensibility invading an Ellison and Ellingtonian universe. Fragments and murmurs rearrange into streams through Ornette’s tone. He’s displaced. And what is called jazz music is too. He cannot be Charlie Parker or Sonny Rollins, and his personal sound is that of sultry disorientation sometimes and precise orientation at others. Its inversions cause Miles Davis to punch him in the face, I think is the rumor.

Friendships worthy of the name are improvised and always rearranging like a Monk composition, staggered into meaning “in the break” — Fred’s phrase. I hear it as drum break and heartbreak, but also big break, breakthrough. The acoustics of all the men and women from the South migrating West to break into song. Their territory shall be the universe, their recording contracts read. Sorrow song that goes down easy. When the muse dries up there or is gentrified by Hollywood, they pile in a car together and drive to New York. As their sons and daughters, we repeat this cycle like a reflex — South, then West, then Northeast. We demand: Take me seriously, leave me alone, watch me change the music. Both New York and Los Angeles are listless muses for this driftless attitude of necessity among the new breed.

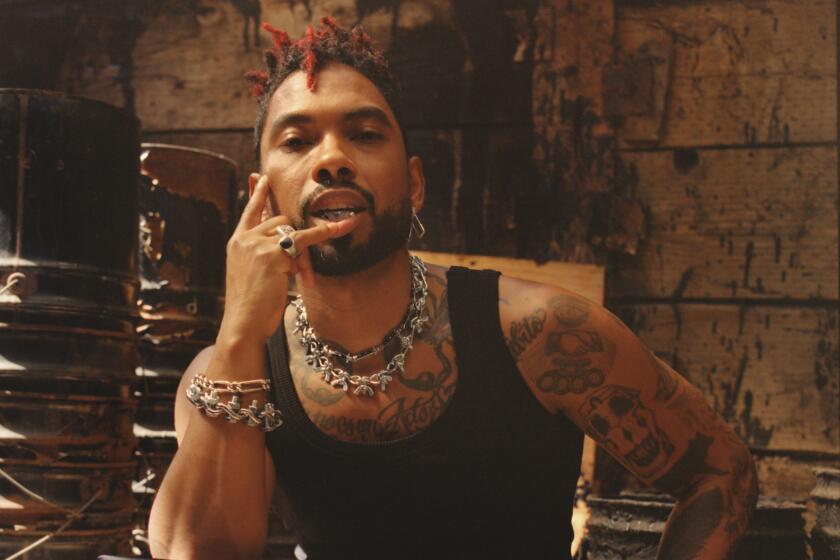

Having experienced the most spiritual growth of his life in the last year, the songbird from San Pedro is finally ready to fully share himself — and his first album in six years — with the world.

Monk was raised in New York’s San Juan Hill neighborhood. He was from North Carolina. Maybe in living there, Fred spoke to him. I speak to him still, in code.

Some of my favorite Monk recordings are from the West Coast. One was at a live concert in Palo Alto, of all places, the current technocratic jungle of soullessness that was once upon a time graced by a legend in his best and most poignant form, circa 1968. And one in Los Angeles at a Black-owned club that was active during the 1960s, the It Club.

Eventually, I moved to L.A., and Fred moved to New York. The Blue Whale closed, and all the clubs were fragile with vacancy until the acoustics of collective improvisation turned into emblems of collective isolation taunting its listeners with a former togetherness. Something fundamental in our spirits was endangered and enlivened then. We started listening together on Zoom and invited others to join us. We made an etheric club. There was a strange intimacy in the distance, an echo of friendship, which brought clarity and dynamism to a world that had grown too complacent and ruined by forced alienation. I think here of the jazz standard “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Your Face.” We embraced the maudlin digital commons until they were ecstatic jazz venues and “radio imaginations,” the term Fred discovered in Octavia Butler’s archive in Los Angeles. A term that cannot be unheard.

The circle was unbroken. During that same era, Fred and I worked on a recording of Henry Dumas’ short story “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” set to jazz music I sampled. The title is prayer and the story loops into a mercy killing of inept and inadequate spectators.

Are you in the right jazz club at the right time, for the right reasons? Are you a charlatan, or do you mean it when you proclaim beauty is a rare thing and all of it lives in this music?

What I know of my friend is that he makes the world safe for sincere listening, for what cannot be said in a place or region or geography outside of sound itself, which is the first world of the soul.