L.A. Affairs: How a trip to Death Valley healed my broken heart

- Share via

Our relationship was bookended by nature. Just days after a chance meeting in Sequoia National Park, we started a long-distance relationship. We considered our first “date” canoeing on Sequoia Lake.

I’d spent so much of my 20s being scared of commitment, yet somehow he was the first person with whom I felt I could express those feelings and work through them. He was so charismatic and radiated positivity. He made me laugh. And he pursued me, a rarity for me. In those early days, we FaceTimed and called each other daily. He was living in the Midwest. But he said he’d wanted to move to Los Angeles for years.

And so, three months into our fresh new relationship, he did. Sort of. He stayed with me for a month. But he struggled to find a job right away, and the credit card debt was piling up. He headed back to the Midwest, where he could live with family while getting back on his feet financially. We continued dating long distance. I felt guilty, though, like I had pressured him to live here before he was ready. I was convinced that this person — the first person I’d wanted to seriously date in my adult life — was maybe my person. But the honeymoon phase was over.

My therapist had helped me to work out that the third date would be the polite time to let a guy know about my mental health.

Then the pandemic hit.

Our push-and-pull long-distance relationship continued for another five months before he decided he was ready to try Los Angeles again. This time, he had a job lined up at a warehouse. He also had a plan: He’d stay with me for two or three months, and then he’d get his own place. Despite the fact I already had two roommates and we were all largely working from home, I thought we could manage this. It was only temporary, after all.

But he kept stumbling. His plans to find his own place, to move in with friends, fell through over and over. Six months later, he left for the Midwest. Again. He claimed it would be for only a few weeks, to regroup. But we both knew better. A month later, we broke up over FaceTime. I wailed in the empty bathtub, fully clothed. I’d been heartbroken before, but never like this; this was my first serious relationship and therefore my first serious devastation.

There was more upheaval: My landlord put the house I was renting in Highland Park on the market, so I had to move as well. For weeks, I could barely eat. I had such uplifting Google searches as “How to find your life’s purpose after a sad breakup” open across multiple devices. I was receiving self-help books in the mail that I barely remembered ordering.

Not a day goes by that I do not miss him or think about whether we might still someday have our chance.

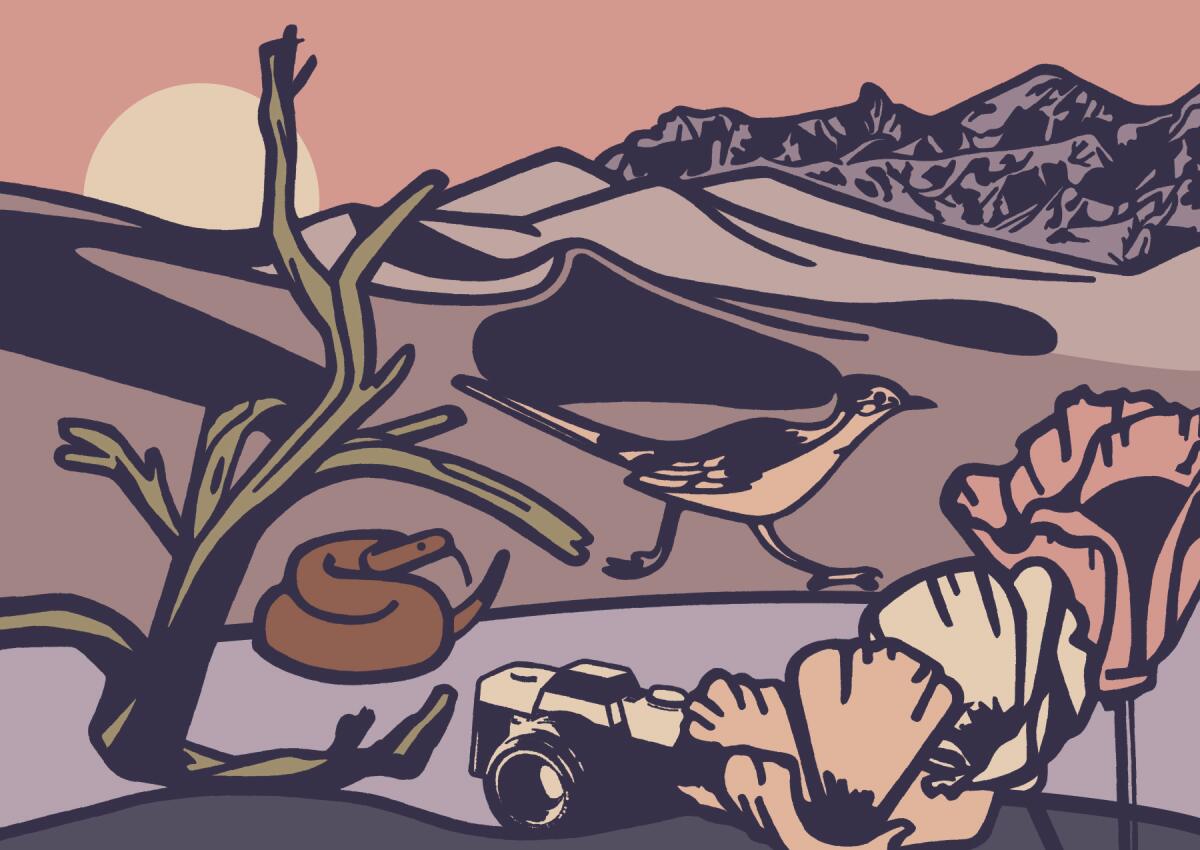

In the six years I’ve lived in California, I’ve crisscrossed the desert almost every year, traveling to Death Valley to camp and take photographs. For obvious reasons, I never made it there in 2020. After being forced to move out of my home during the pandemic and going through that breakup, I felt like running away.

And that’s what road trips often feel like: running away. Nothing but the now and the necessities required for survival. Where to sleep, what to eat, how many miles until the next gas station. In Death Valley, cell service is hard to come by. It takes almost two hours to drive from one end of the park to the other. A road trip is the ultimate toe dipped into the proverbial pool that is life off the grid.

So as the dust settled from the moving truck, and I was left unpartnered and devastated, it felt like time to return.

What better place to run from heartbreak than Death Valley?

As a freelance photographer, I almost exclusively shoot digitally. Film still feels like an exploratory process for me. So as a challenge to myself I decided to shoot my desert trip entirely on film, using my dad’s old Minolta. A day into the trip, I realized I’d packed only a few boxes of film. No matter, I thought. There’s always Walmart across the border in Nevada, an hour away.

Three days later the camera broke. Completely. I thought it was just a dead battery, but after another hour-there-and-back Walmart run for batteries, I admitted defeat. Worse, I’d missed my last sunset of the trip on a fool’s errand.

I considered his words as if they were a fortune teller’s: “Mijo, you’re going to have a very lonely life.”

It wasn’t so much the lack of ability to shoot — I had my digital camera as backup — but the loss of this artifact from my childhood and from my connection with my father.

It felt like yet another bump in the already pothole-dotted road I’d been on for months.

All the feelings I’d been suppressing the entire trip came back, full force. Everything clawed to the surface. I tried to stay away from the “shoulds” and the “I wishes.” But there they were. I should’ve been more understanding of just how hard the move was on my ex. I’ve always known my passion — photography — and I forget that not everyone has such a clear-cut path. I wish I hadn’t been so pushy about expecting him to figure out his career so quickly, sending him job listing after job listing. In retrospect, I think he felt lost here. I wish I had done a better job at communicating and helping him share his fears and hurts with me. I don’t think I realized how bad it was until the end. We were two people who loved each other but weren’t compatible.

Being alone in the desert wasn’t the salve I thought it would be.

I felt like I couldn’t snap out of my cycle of grief. And that’s what breakups are, really: a prolonged mourning for the life we will no longer share.

Several days into my trip, in a CVS parking lot in Pahrump, Nev., just outside Death Valley, I did what I’m fortunate to be able to do: I called my parents. And I cried. I told them about the camera. I told them about how lonely the desert had been — not the good lonely I’m used to, the kind I crave on occasion, but the crushing kind. I told them about forgetting the film and driving an hour to replace batteries that didn’t need replacing, to try to fix a camera that simply wouldn’t work, no matter how much I wanted to fix it.

Not everything can be saved, and sometimes you need three days alone in the desert to remind you of that fact. My dad didn’t care about his broken camera. Not like I had, at least. My parents reassured me that everything would be OK.

A few days after arriving home, I was able to find a replacement Minolta online for less than it would have cost to fix.

There is always another camera and always more vistas.

The author is a freelance photographer and writer. Her website is linneabullion.com and she is on Instagram @linneabullion

L.A. Affairs chronicles the search for romantic love in all its glorious expressions in the L.A. area, and we want to hear your true story. We pay $300 for a published essay. Email LAAffairs@latimes.com. You can find submission guidelines here.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.