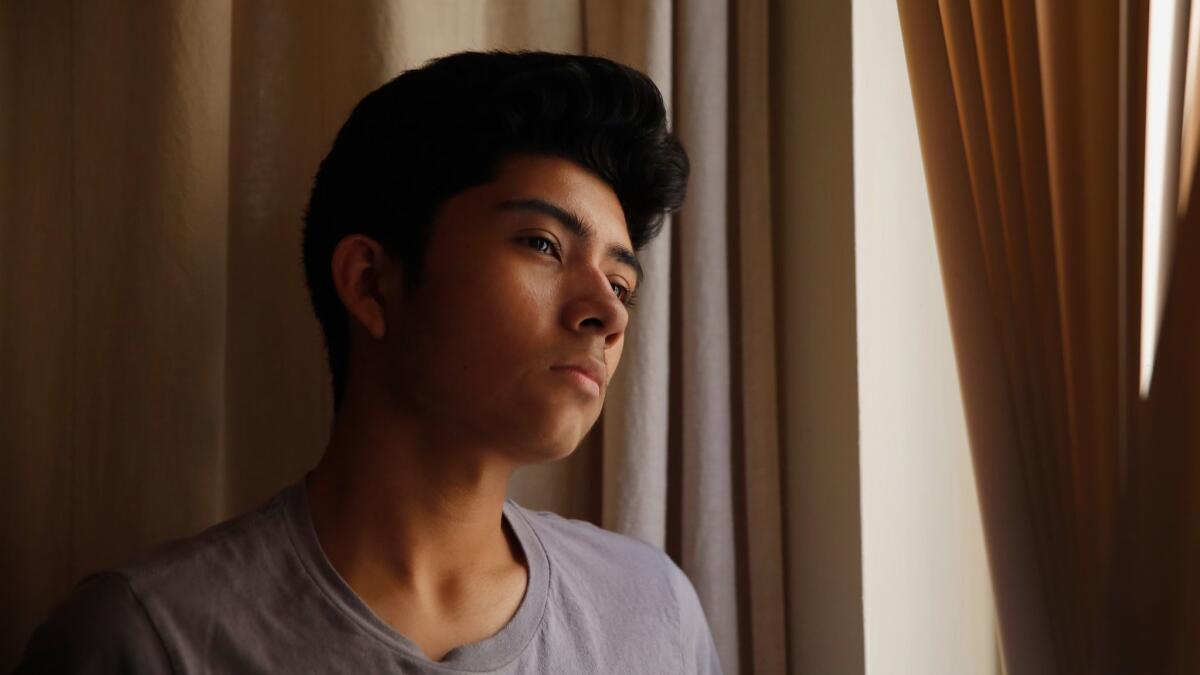

Column: He got into a great college the old-fashioned way: Hard work, big dreams.

Eva Vazquez was at a bus stop on Wilshire Boulevard, on the way to work as a cashier at a discount store near MacArthur Park, when her phone rang.

“I knew it was probably him,” she said.

It was Thursday, March 28. The day her son Oswaldo was expecting to find out if he’d been accepted to the universities at the top of his wish list.

Oswaldo, sometimes called Ozzie by friends and family, had already gotten into several great schools on the strength of straight A’s, a strong SAT score and his years of mentoring and community service.

But Vazquez had seen him sink when he missed the cut at Stanford University, and she’d been praying he would get better news from other top schools. She knew better than anyone how hard her son had worked, for so many years, in Los Angeles and in Mexico.

“Mami,” Ozzie said when she answered her phone. “Guess what.”

::

I met Ozzie and his mother in their tiny Chinatown apartment. Vazquez sleeps on a futon in the living room. Her sister and 13-year-old daughter share the one bedroom. Ozzie sleeps in a small alcove off the living room, where his desk and the dining table are one and the same.

Ozzie, who was born in the U.S., was 5 and a student at Gabriella Charter School in Los Angeles when his parents decided in 2005 that they couldn’t take the anxiety of living illegally in Los Angeles after their visas expired, so the family moved back to a village in the Mexican state of Yucatan. As Vazquez tells it, she and her husband came to the United States on visas in the late 1980s and scratched out a life on the margins. They both worked at a carwash, had three children, but then began to worry that they would be deported and separated from their kids.

When they left for Mexico, they took with them a used computer Ozzie had been tinkering with, and he now says that device helped him get through several tough years.

“I just felt so confused, and I didn’t know how to socialize with people,” Ozzie said of life in Mexico. “As I grew older … I was bullied for quite some years. Not just verbally, but also physically…. It was one of the worst times of my life. People saw me as not really from Mexico. I was a foreigner, and also just an ignorant kid.”

When he wasn’t working in the restaurant his family ran, the screen on Ozzie’s computer was his escape hatch. The small desktop was old and slow, he said, but it transported him to other worlds, and he taught himself how to program, code and design his own rudimentary video games.

Ozzie’s older sister returned to Los Angeles after a short time in Mexico to live with their mother’s sister, and she ended up graduating from UCLA. Ozzie began thinking he wanted to follow in her footsteps, even though he was torn about leaving his family behind in Mexico.

Four years ago, he moved into the Chinatown apartment he now lives in, with his aunt as his host. When he returned, he had forgotten most of the English he learned as a child. His mother told him to read as many books as he could.

“Here’s my boy Steinbeck,” Ozzie said as he walked over to the bookshelf to point out some of his favorite authors.

::

At Los Angeles Unified’s Los Angeles School of Global Studies, just west of downtown, Ozzie was a top student from the start.

“He’s naturally intelligent, but he has put in a lot of hard work,” said Diane Kantack, Ozzie’s counselor. “He’s an amazing young man and always humble…. And Oswaldo is always the first one to volunteer to help someone else out.”

The school has no Advanced Placement courses, so Ozzie began taking classes at Los Angeles City College three years ago, including computer science, calculus and biology, and he said he’s close to having an associate of arts degree. He has also been a volunteer at a nonprofit organization called Peace Over Violence; has spoken to various groups about homelessness, bullying, violence and abuse; and last summer he got into a summer journalism program at Princeton University.

“I want to start off as a computer programmer,” Ozzie said of his career plans, “but my ultimate goal with computer science is to conduct research on artificial intelligence and machine learning for humanistic applications…. Once I retire, I want to be a teacher at my high school and just give back, and try to make kids be more engaged and have fun.”

Ozzie got into all the California State University campuses he had applied to. The Stanford rejection was followed by two more — from Princeton and MIT.

As historically black colleges struggle across U.S., Bennett College fights to stay afloat »

When news of the college cheating scandal broke, with stories of wealthy parents allegedly paying bribes to inflate their children’s SAT scores and buy their way into top universities, Ozzie and his mother worried that his hard work might not be enough to get him where he wanted to be.

But he got into UC San Diego, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, Fordham and UC Santa Barbara, and then he got good news from one of his dream schools — UCLA.

“I was overjoyed,” Ozzie said.

And all of his acceptances came with even more good news. He was offered full-ride scholarships.

But before making any decisions, Ozzie wanted to hear back from UC Berkeley and two Ivy League schools — Dartmouth and Harvard. And he wanted to do more research into which school would offer the best possible combination of computer science and liberal arts.

At 3:30 p.m. on March 28, he went to his counselor’s office. The moment had arrived to go online and check the latest application results. With Kantack watching — and, she says, praying — he checked UC Berkeley first.

“It says ‘congratulations,’ and I see all this confetti on the screen, and I started screaming, ‘Let’s go!’ ” said Ozzie, who hugged Kantack.

California’s broken charter school law has defied reform. Can Newsom break the gridlock? »

They were both too nervous to check Harvard and Dartmouth. Ozzie said he paced Kantack’s office, thinking back on the difficult time away from his family, on his aunt’s generosity in hosting him at her apartment, on all the hours of study and community service. He was content with the good news he’d already gotten, he thought. His hard work had already paid off.

Still, his hand was shaking as he logged on to see the Harvard decision.

“I tried to move the cursor, I finally hit it, and all I see is ‘congratulations’ in bold, and I just go nuts. I stand up, I start screaming, and I believe I’ve never screamed that loud.”

Next up, Dartmouth.

Same result.

Avenatti accused of embezzling nearly $2 million that NBA player paid ex-girlfriend »

His first call was to his mother, who got legal entry to the U.S. a year ago after years of waiting for the paperwork to come through. Her husband is still waiting for approval.

“I started screaming at the bus stop,” Eva Vazquez said. “I wanted to run, but I had to get to work. I was crying on the bus and people were looking at me like, ‘What’s going on with this lady?’ ”

It would be a couple more weeks before Ozzie decided to go to Harvard, but his mother seemed to know where he was headed the day he called.

Vazquez was still crying so hard when she got to work, her boss thought she was distraught. She explained what happened, then took her post at a cash register. The store security guard saw her, still crying, and asked what happened.

“I said, ‘Do you really want to know? My son got into Harvard.’ And the customers started clapping.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.