Once easily recognized, signs of measles now elude young doctors

It was spring of 2014. Dr. Julia Shaklee Sammons looked around and saw trouble.

An infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, she had read the headlines about new measles cases — including outbreaks in California and Ohio — and decided it was time to speak out.

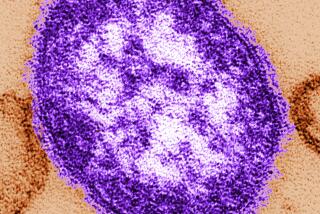

Writing in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine, Sammons implored doctors to get more familiar with the disease. In two tightly packed pages, she described measles’ potentially deadly effects and outlined how to diagnose it. She included archival photos to drive her point home: A tow-headed boy covered in an angry rash in 1963. A child’s upper lip pulled back to display tiny white spots, an early sign of measles that sometimes can lurk unnoticed.

She knew how badly coaching was needed.

Like many younger physicians, Sammons, who graduated from medical school in 2006, trained when the disease was no longer an issue in the United States. “I have not cared for a patient with measles,” she said. “I hope I never have to.”

A decades-long effort to immunize American children managed to wipe out the last homegrown cases in 2000. But the virus still can arrive here from other countries and spread.

Today — as California faces its largest outbreak since the disease was declared eliminated — some worry that the battle against measles has become a victim of its own success.

The virus is now so rare that medical schools don’t dwell on it at length. Lack of familiarity can make medical providers, the vast majority of whom have never seen a sickened patient, slow to recognize the potentially deadly, and highly contagious, disease.

“Doctors aren’t thinking about measles because they haven’t seen it before,” said Dr. Mark Sawyer, a pediatrician and infectious disease specialist at UC San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital. “Diagnosis is delayed, the patient isn’t isolated, and they end up managing to expose other people until somebody goes: ‘Wait a minute — this is measles!’”

It’s usually a senior doctor who sees it, Sawyer said.

The current outbreak began a week before Christmas and thus far has sickened at least 87 people in seven states and Mexico. About one in four of the 73 patients from California, who range in age from 7 months to 70 years, has required hospitalization. Most had visited Disneyland. Many were not immunized. A number initially were misdiagnosed.

One year before the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1962, there were 481,530 reported cases nationwide, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2004, there were 37.

Aspiring physicians still learn about the virus in medical school, but they read up on its biology and symptoms at the same time as they’re being introduced to a multitude of illnesses they’re far more likely to encounter.

“It’s not something you spend a great deal of time on at all, for obvious reasons,” said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville.

Schaffner said he thought the Disneyland outbreak — and the pockets of undervaccinated children that have fueled it — might lead medical schools to increase their emphasis on teaching measles. But the latest generation of doctors still won’t get hands-on experience.

“In the bad old days, any grandmother could walk past a child with measles and say, ‘That’s a child with measles,’” Schaffner said. “It’s pattern recognition. And if you haven’t seen it before, it can be puzzling.”

With measles in particular, which can resemble many other illnesses in its early stages, seeing is understanding, said doctors who had treated afflicted patients. Textbook pictures can’t fully convey what the signature rash looks like. Infected kids are uniquely irritable.

“There’s a miserableness quotient,” said Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician and outspoken immunization proponent. “You can read about it, but there’s nothing like seeing it.”

Sawyer said he recently asked a group of pediatric residentswhether they had ever seen measles. None raised their hands.

It’s a problem, Sawyer said, because the virus is so contagious.

“There are a lot of infectious diseases physicians don’t see in training, but most don’t have the same consequences if you miss it for a little bit,” he said. “The problem with measles is, if you miss it, you put people at risk.”

More than 90% of people who don’t have immunity to measles — either through vaccination or from having had the disease — will get sick if exposed to the virus, which can survive for up to two hours in the air.

Dr. James Cherry, a UCLA research professor and principal editor of the Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, said it was important for physicians to remember that fever, cough and runny nose are initial signs of measles. About two days after those symptoms begin, white lesions known as Koplik spots emerge inside the cheek. Only later does the rash appear.

Officials at the Orange County Health Care Agency and the California Department of Public Health said they were working hard to make sure doctors knew what to look for to make a measles diagnosis and to keep providers updated on the current outbreak.

This isn’t the first time California physicians have had to educate themselves about measles, said Dr. James Watt, chief of the division of communicable disease control of the state public health agency.

Watt was a pediatrician in training during the outbreak of 1989-1991.

“What I remember very vividly was that all over the hospital there were signs that said, ‘Think measles.’ There were pictures of children with measles,” he said, as well as placards reminding doctors of key symptoms.

Dr. Deborah Lehman, a pediatric epidemiologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, said she first encountered the illness during the late 1980s outbreak, when she was in training at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

Two sisters came to the hospital in the middle of the night suffering from symptoms that she and her colleagues thought must be meningitis.

“Measles was the furthest thing from my mind,” she said.

A seasoned pediatrician arrived at the children’s bedside in the morning. He made the correct diagnosis right away.

Twitter: @LATerynbrown

Twitter: @ronlin

Twitter: @RosannaXia

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.