Families lay shooting victims Tin Nguyen and Isaac Amanios to rest

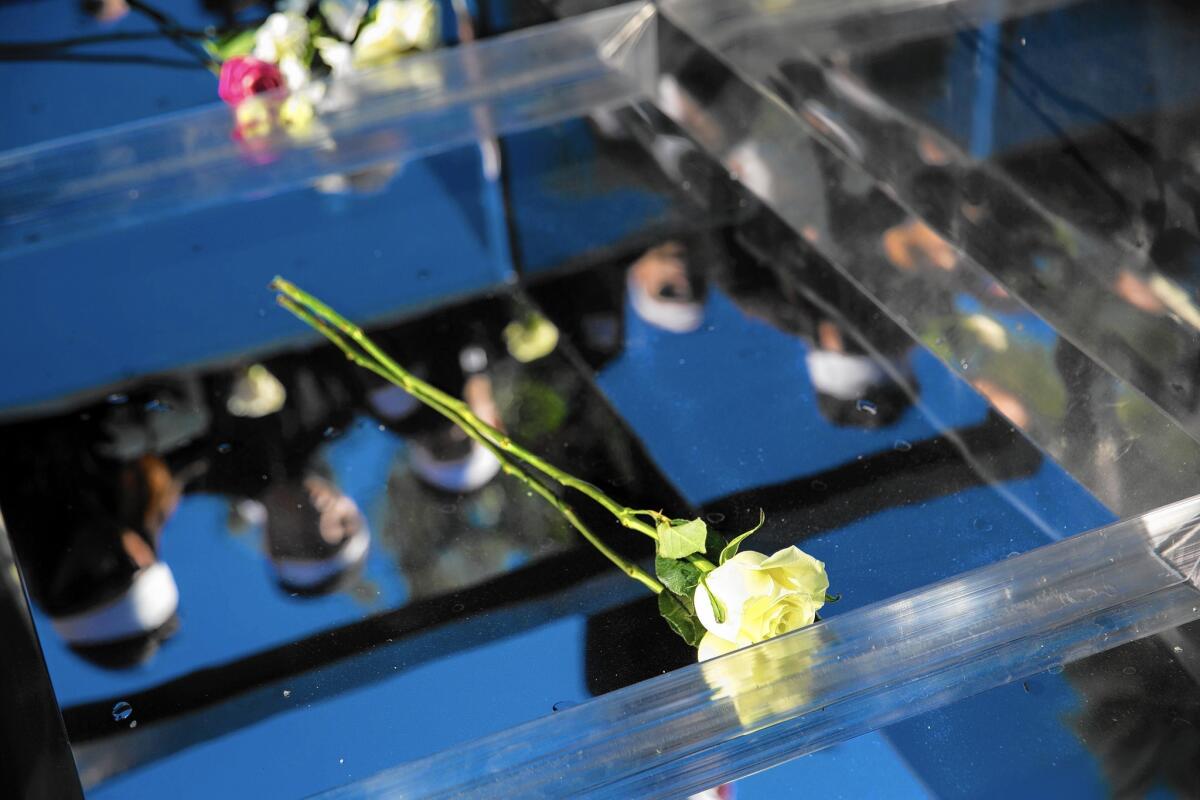

Flowers are placed in the burial vault in Huntington Beach on Saturday at the funeral for Tin Nguyen, 31, one of the victims of the deadly San Bernardino terrorist attack.

Tin Nguyen wasn’t just the glue that held her family together. She was their “super glue,” a patient, happy young woman “with a heart bigger than the sun,” family members said.

Nguyen was just 8 when she and her mother fled Vietnam to rebuild their lives in a place they considered safe. Here, Nguyen built for herself a life of love. She stood out for her infectious cheer amid a large extended family that gathered for weekly Sunday dinners. And she’d recently been trying on wedding dresses because she was going to marry the love of her life in 2017.

But at 31, Nguyen’s life was cut short. She and 13 others were killed Dec. 2 when their colleague, Syed Rizwan Farook and his wife, Tashfeen Malik, opened fire on their county public health department holiday potluck at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino.

On Saturday, more than 500 mourners filled the pews at Nguyen’s beloved St. Barbara’s Catholic Church in Santa Ana to pay their final respects.

The Mass — set amid towering Christmas pines and a wreath of pink and white blooms — was laced with the flavors of two cultures, alternating between English and Vietnamese, with some of Nguyen’s family members wrapping white bands of mourning around their foreheads in Vietnamese custom.

Nguyen was a model of “filial piety,” Father Joseph Nguyen Thai told the congregation, delivering a sermon focused on the power of love overcoming the threat of terror. “We are here to pray, fighting against guns and ammunition.”

Nguyen’s uncle, Ham Nguyen, said that although his niece liked all things simple, her mother chose the best robe she could find for her daughter to wear in her casket, instead of the wedding dress she will never wear.

Earlier, at her wake, Nguyen’s mother, Van Thanh Nguyen, wrote in a letter: “Mom is sorry because I did not have enough strength to protect you.” She was afraid, she wrote, that her only daughter died alone, cold and terrified in a room “completely destroyed by bullets.”

Nguyen, a San Bernardino county health inspector, was killed on her boyfriend’s 32nd birthday. The night before her death, they had toasted the occasion at a shabu-shabu restaurant. She and San Trinh had dated for nearly six years and had planned an engagement in a few months, followed by a wedding in 2017.

Trinh stood at the side of Nguyen’s hearse, stoic, both arms hugging a picture of his beloved. He has wondered, endlessly, why they didn’t marry earlier.

As he leaned on the car, a cousin motioned to him. A burial awaited. He bowed to the crowd, climbed in and shut the door.

In Colton, hundreds of people filled the pews — and an overflow room — at the hilltop St. Mina Coptic Orthodox Church for the funeral of another victim, 60-year-old Fontana resident Isaac Amanios, a native of Eritrea who worked as a San Bernardino County health inspector for 11 years.

In the audience were members of the tight-knit Eritrean diaspora living in Southern California, the women wrapped in long shawls, covering their heads.

Eight pallbearers — young men in dark suits and white gloves — carried Amanios’ wooden casket adorned with crucifixes through the ornate sanctuary, where the morning sunlight streamed through the windows. His widow, Hiwet, screamed with grief.

The smell of burning incense filled the room as the crowd chanted prayers.

Amanios immigrated to the United States in 2000, in search of stability and a better life for his wife and three children. He was remembered at the service, which veered between English and Tigrinya, as a man devoted to his family, even his extended family, who would fly across the country and overseas to attend weddings, baptisms, graduations and birthday celebrations.

Amanios’ children — sons Yosief and Bruk, and daughter Milka — described their father as someone who taught them to work hard and to always value their education.

“My dad told me he married my mom because he wanted to have a daughter just like her,” Milka Amanios said. “Little did he know I’d turn out just like him.”

She said she was outspoken and strong, and that her father always supported her and welcomed spirited debates.

“I was lucky enough to never have to doubt my parents’ love or their pride in me,” she said. “He was convinced I could do anything, to the point where I owe my confidence to him.”

As photos of Amanios played on a projector, his wife sobbed and rocked back and forth, reaching her hand out to his image as her children held her.

MORE ON SAN BERNARDINO

Analysis: After the tragedy, elected leaders were notably absent

FBI hunts for electronic trail that could link shooters to foreign terror groups

Enrique Marquez focus of intrigue and mystery in terrorism probe

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.