Decisions of Long Ago Shape the Union Today

In the winter of 1977, at the height of his union’s power, Cesar Chavez summoned the leaders of the United Farm Workers to a mountain retreat in the Sierra foothills. They found themselves in an ultra-clean compound where recovering drug addicts with shaved heads wandered the grounds dressed in uniform overalls.

The purpose soon became clear: Charles Dederich, the flamboyant founder of Synanon, welcomed his guests to the rehabilitation facility and explained the rules of the Game, a therapy designed for drug addicts. A dozen players would gang up on each other, “indicting” a participant for bad behavior by hurling abusive and often profane invective.

FOR THE RECORD:

UFW —A series last month on the United Farm Workers contained three factual errors about the history of the labor union and its related organizations. Health clinics operated during the 1970s were run by the UFW-affiliated nonprofit National Farm Workers Health Group, not the union directly, as reported Jan. 8. UFW officials said that a Fresno developer who partnered with Cesar Chavez to build for-profit housing donated his services and did not split the profits from the developments, as reported Jan. 9. And UFW officials said a school bus abandoned in a back field at union headquarters was not one of the buses used to transport boycott volunteers across the country in the 1970s, as stated in the Jan. 9 article, but was left by a peace activist who never returned to claim it. In addition, the Jan. 8 article reported that the UFW “board deleted all specific references in the UFW constitution to agricultural workers, including the preamble.” To clarify: The board deleted the entire preamble and amended the constitution to include all categories of workers, so that the UFW constitution no longer applied only to agricultural workers and related laborers.

The UFW board members had arrived expecting to hash out a new strategic plan after a string of victories, including a pact to keep the rival Teamsters union out of the fields. Instead, they found themselves in the Game room, where some observed from elevated seats as others accepted a challenge to play in the recessed pit.

In retrospect, some UFW leaders came to view the Synanon meeting as a watershed, the first clear signal that Chavez had veered off course and shifted his focus away from organizing farmworkers.

“We were so close,” said Eliseo Medina, one of the UFW’s top organizers and a board member until 1978. “And then it began to fall apart . At the time we were having our greatest success, Cesar got sidetracked. Cesar was more interested in leading a social movement than a union per se.”

The story of Chavez’s erratic leadership during a pivotal period emerged in bits and pieces at the time but has not been fully told before. Many who left the UFW were for a long time reluctant to discuss the union for fear of harming an institution and cause they still believe in deeply. Today, an extensive review of historical letters, minutes, memos and tapes of meetings, along with scores of interviews with participants, paints the first detailed portrait of a critical and turbulent time.

The decisions Chavez made a quarter of a century ago shaped the union and Farm Worker Movement today, turning it away from the core mission of organizing farmworkers. His actions drove out a generation of talented labor leaders; he replaced them with handpicked loyalists — including many of the people now running the organization. He quashed dissent and increased his control just as the union’s growth made that more problematic.

He became increasingly concerned with traitors, spoke of malignant forces and publicly purged the young and old. He turned on proteges, some of his earliest supporters and close friends. His actions so baffled them that many years later they still seek explanations.

For a decade, he had been an internationally acclaimed, visionary leader, a brilliant strategist who inspired dozens of talented people to follow him. He had built a volunteer movement that galvanized public support to change the lives of farmworkers, bringing them dignity as well as higher wages. In California, he had pushed through the only law in the country that gives farmworkers the right to vote for union representation — establishing a legal framework that the UFW had been quick to exploit, winning dozens of elections and contracts.

As the UFW board gathered in February 1977 at the Synanon campus, there was a moment of opportunity to solidify those gains. Instead, Chavez became focused on building a community at the UFW’s rambling headquarters in the Tehachapi Mountains. He railed about inefficiency, obsessing about the cost of telephone bills or questioning a $7.20 brake repair bill. He led committees that discussed celebrating movement anniversaries instead of birthdays. He studied mind healing and practiced curing illness by laying on hands.

For more than a year, Chavez required staff members to drive as much as five hours every weekend to La Paz, the union’s headquarters, to play the Game.

“Cesar was struggling with disloyalty within the ranks. Dederich says: ‘This is how you deal with it.’ The Game came to La Paz for control,” said Chris Hartmire, a close Chavez aide who became the “game master” at La Paz, setting up the encounters.

Disciples said Chavez’s eclectic interests and commitment to a movement were fundamental to his vision. “When people would accuse him of not being a union guy, he kind of took pride in that,” said his son, Paul Chavez, who has carried on the social entrepreneur legacy by building affordable housing.

Said Marc Grossman, a Chavez public relations aide for many years and still the UFW spokesman: “He took as much personal satisfaction in converting someone to vegetarianism as to trade unionism. He really did.”

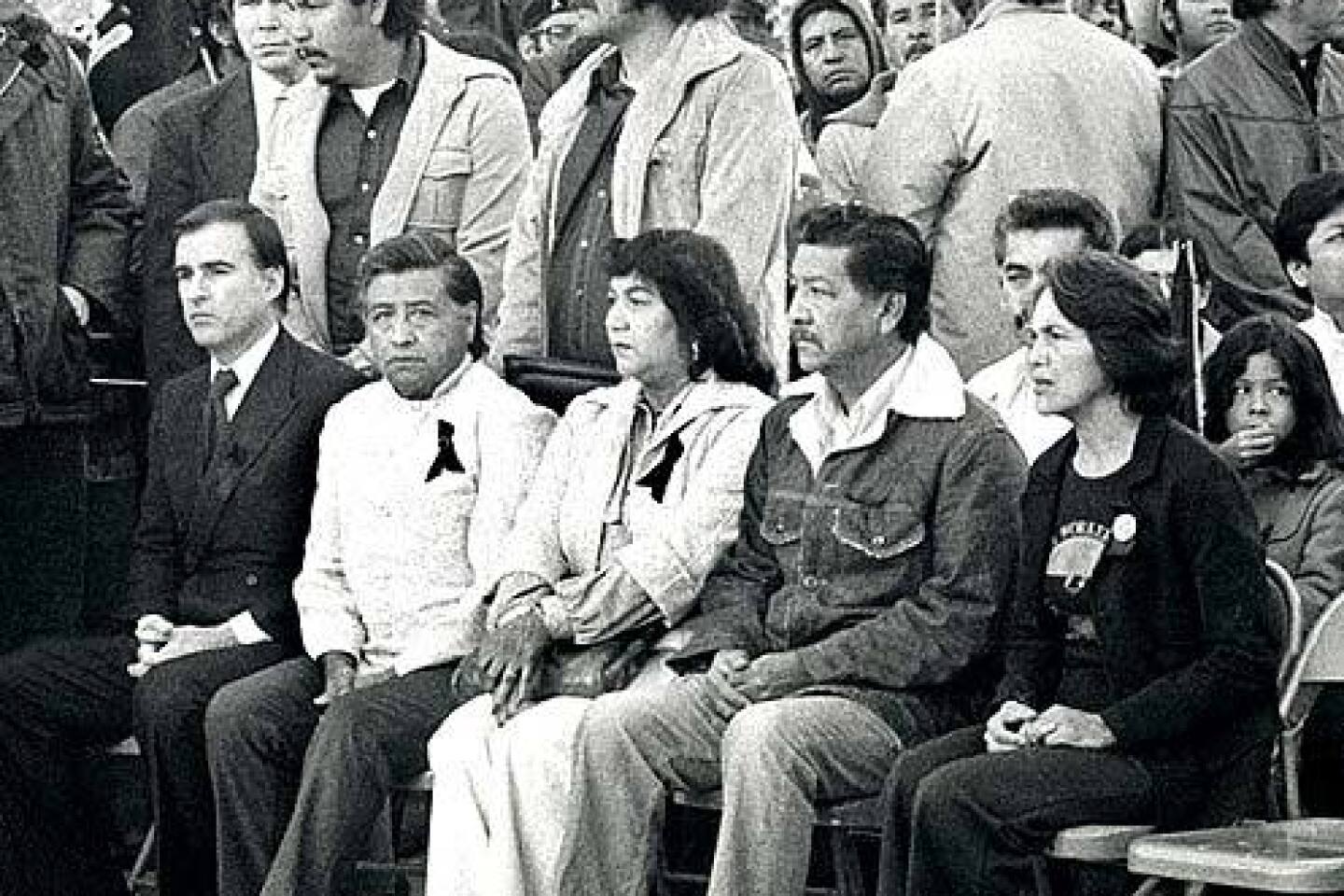

Dolores Huerta, co-founder of the UFW, said in an interview that Chavez’s brilliance was often misunderstood, and that during the turbulent years of the late 1970s he acted to defend the movement he built when it was under attack from insiders who thought they could run the union better. “It’s very hard to build an organization, but it’s very easy to unravel,” she said.

Whether Chavez initiated the changes or responded defensively, the net result was the same. By 1982, he had driven out dissenting voices on the board, among the staff and in the fields. Key staff and architects of the union’s early success were gone, along with the next generation of leaders in the fields. The UFW never regained the same momentum as a labor union for farmworkers.

1977: The Purges

In December 1976, Nick Jones, a longtime left-leaning volunteer who had been directing the UFW boycott, was accused by Chavez of masterminding a communist conspiracy to bring down the union. “I was flabbergasted,” said Jones. “It demoralized me more than anything else in my whole life.”Jones quit, his abrupt departure triggering protests from around the country. The boycott had been a powerful weapon for the union, publicizing the harsh conditions for farmworkers and exerting pressure on companies to sign contracts. A mix of volunteers, students and farmworkers, the boycotters were a close-knit group. Many moved from city to city, and Jones was a well-known and liked leader.

“An atmosphere of suspicion has developed, in which preposterous accusations can be made and acted upon indiscriminately. People have been fired on the basis of flimsy charges against them,” the Seattle boycott staff wrote to Chavez, one of many letters that demanded either an explanation or an apology.

The response was one that would be offered repeatedly in the coming years: Cesar knows things you don’t, and he is protecting the union. Hartmire, a much beloved Chavez confidant and Presbyterian minister, became the official apologist, and his reassurances kept many staff members in the fold.

“People would go to Chris and say, ‘I don’t know about this,’ and he would say, ‘I know it seems that way, but you don’t see the whole picture; Cesar does,’ ” said Ellen Eggers, who worked as a lawyer for the UFW.

In meetings and memos, Chavez stressed the need to foster community at La Paz, the isolated former tuberculosis sanatorium east of Bakersfield where he had moved the union in 1971. Chavez urged a greater role for children who had grown up in the movement and understood its values. He criticized board members for tolerating bad and subversive behavior because they were desperate for staff. He brought in management consultants and tried to find the ideal structure.

“The big problem we face is we haven’t made up our minds what kind of union we want to be. Or if we’re going to be a union,” he told a group of staff after they had played the Game.

At a community meeting on April 4, 1977, that became known as the “Monday night massacre,” volunteers were viciously attacked and expelled for sins ranging from smoking pot to betraying the union. “It was planned, and it was brutal,” said Larry Tramutola, then a high-ranking union leader who participated in the denunciations.

Deirdre Godfrey was one of those expelled; she described in a letter to the executive board how security guards followed and threatened her that evening when she made a call to find a place to live: “I have never spent such a fearful night . I shall never forget the frenzied, hate-filled faces and voices of people who had been warm and friendly with me right through to the hour of the meeting.”

Over the next year, Chavez continued to denounce popular workers as communist infiltrators. A volunteer in her 70s was turned out with no place to live. In the middle of a wedding reception, Chavez vilified a young woman who had lived in his house as a teenager, ordering her thrown off the grounds just weeks after she had successfully negotiated a contract.

Huerta said it was a time when security had become a major concern in the loose-knit organization, after Chavez received death threats. “If Cesar was a little paranoid, there’s a reason for it,” she said.

Some former UFW leaders now say they had qualms about the purges, but justified or ignored them. They were winning elections. Some of the threats were real.

“You could see you were making a difference. You could put up, rationalize, accept, maybe even believe in it, as long as something bigger was happening,” Tramutola said.

“I hoped it would go away,” said Medina, then a vice president on the board. “It never did.”

For many years, Jones, the onetime UFW boycott director, blamed Medina and other board members for not standing up to Chavez. “But no, it was all of us,” Jones said recently. “All of those people who used to roll out the carpet and lay it at his feet — he cut their throats.”

1978: Turmoil on the Board

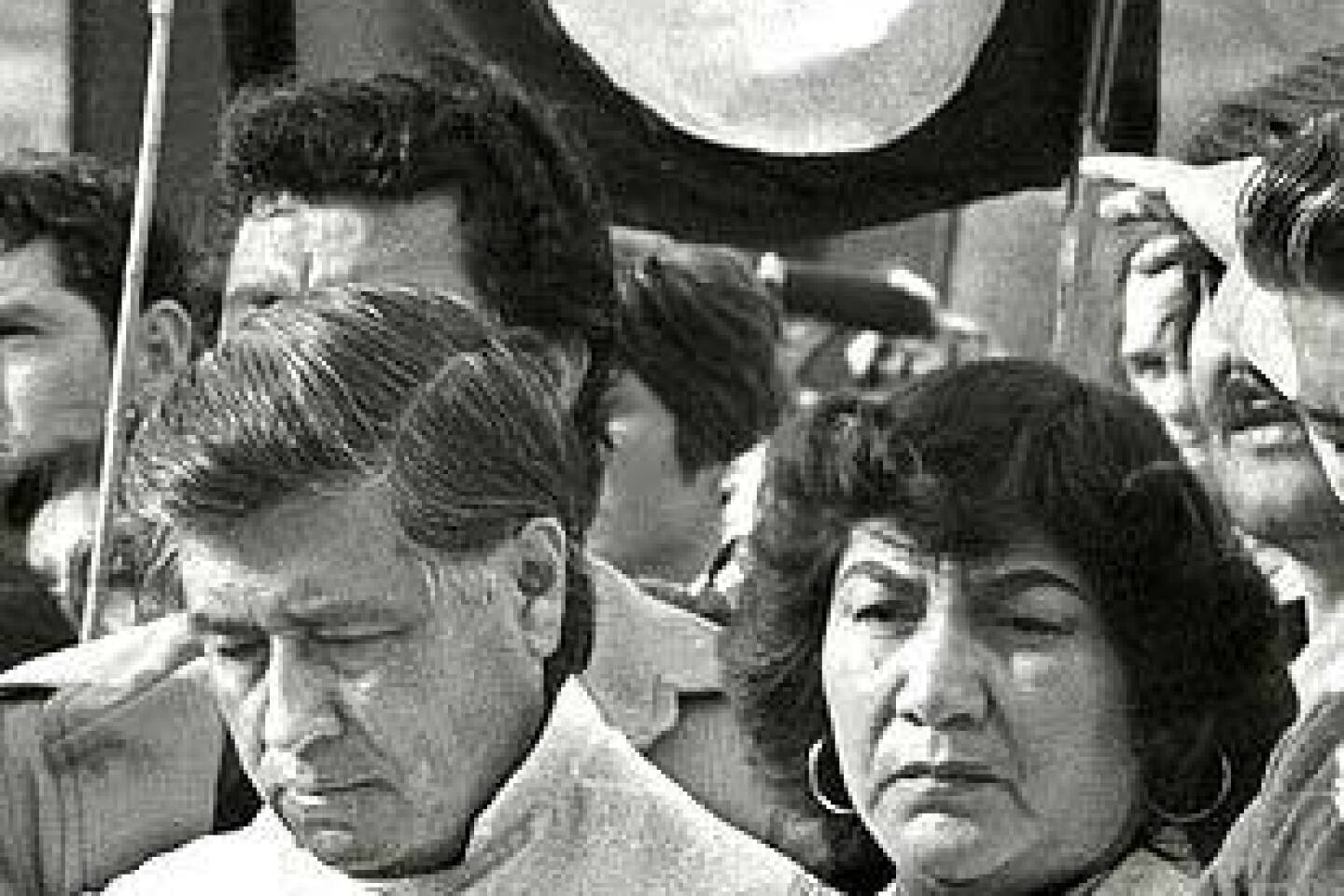

Marshall Ganz, the son of a Bakersfield rabbi, had dropped out of Harvard and joined the UFW after a stint in the civil rights movement in the South. Passionate, fluent in Spanish, more popular among workers than staff, Ganz was a shrewd and relentless organizer who exuded brash confidence and backed it up with results. He was close to Chavez in an almost father-son way that caused resentment and occasional antipathy even among allies.Ganz had helped oust Jones, but by 1978 he had grown troubled by Chavez’s reluctance to tackle key issues: Should the union focus on the vineyards, its symbolic heart, or on the vegetable fields, where it had built a strong base of support? Should organizers try to win more elections and add members, or consolidate and work on administering contracts effectively?

Ganz laid out his criticism in a private letter; Chavez shared it with the board. At a March 25 meeting, Ganz explained to board members what prompted his scathing letter:

“We had all these problems out there that we had to deal with that were crucial. It was very frustrating to me, what I felt was the lack of planning, the lack of direction, just sort of going from here to there, and frittering resources and time,” Ganz is heard saying on a tape of the board meeting. “And in the meantime, a lot of Cesar’s attention seemed to be on the Game and on Synanon and on La Paz.”

Ganz warned the board that he saw another looming problem: The union was not giving real power or responsibility to workers or involving them in decisions: “We just seem to assume that whatever way we decide to go is automatically OK. It’s not automatically OK.”

Ganz’s base was Steinbeck country, the rich fields of Salinas, where the UFW had 17 contracts covering 7,200 farmworkers (about the size of the entire union today), including many of the most ardent and militant union supporters.

Salinas was also home to the UFW’s legal department, 18 lawyers who bailed out picketers and battled growers under the direction of Jerry Cohen, a young lawyer recruited by Chavez. Cohen relished a fight, and he excelled at using irreverent tactics to push the envelope and score victories.

“He was my idol,” said Salvador Bustamante, a farmworker who wrote a poem about Cohen after watching him negotiate with growers. “I loved seeing him deal with them, avenging every affront they ever did to me.”

Cohen had helped craft many of the union’s early victories, from the law protecting union activity in the fields to the pact keeping Teamsters out. The legal department was in Salinas because he refused to live in La Paz.

Cohen had thought Chavez was comfortable with that decision, which placed the lawyers closer to many courts, though distant from union headquarters. But at the Synanon meeting, Cohen discovered otherwise: The lawyer got “Gamed” about why he abandoned his friend Cesar and moved to Salinas.

In an organization where most staff were volunteers, paid $5 a week plus free room and board, UFW lawyers had special status: They earned about $600 a month. In the spring of 1978, each lawyer asked for a $400-a-month raise.

Chavez seized on the requests and turned them into a referendum on the larger issue of whether the union would have paid staff. He painted the lawyers as greedy and unwilling to sacrifice like everyone else and said acceding to their demand would be a prelude to destroying the volunteer organization. He asked the board to vote in support of the status quo, effectively dismantling the legal operation.

Cohen and Ganz countered that a stable of professionals who could afford to stick with the union was critical, particularly as the contracts in Salinas were expiring. The debate was so heated the executive board adjourned for 10 days. Chavez eventually won by one vote, and most of the lawyers left soon after, replaced by a smaller operation at La Paz.

“It wasn’t about money; it was about control,” said Cohen, who resigned as chief counsel but stayed during a transition.

To Medina, the vote was one more sign the UFW was headed in the wrong direction. A farmworker who had risen quickly to a leadership position, Medina was widely viewed in the fields and among staff as the logical successor to Chavez. But Medina had been unhappy for months. “We sort of had become focused on everything except going out and organizing farmworkers,” he said.

Organizing was what he excelled at: In the three months he had run the department, Medina reported at the June board meeting, the UFW had won 13 elections and gained 3,030 members.

Just three months later, Arturo Rodriguez, who has since become UFW president, gave a very different report: He told the board that organizing prospects were grim.

Asked what it would take to win elections, according to minutes from the meeting: “Brother Artie responded that he wasn’t really sure . Brother Cesar said he doesn’t think we can do very much about organizing right now.”

The last item on the September agenda was Medina’s resignation. Ganz, though more a competitor than a friend, argued that the board should not accept it. Chavez made no attempt to sway Medina.

“That removed the one credible alternative to Cesar,” Ganz said. “It changed the dynamic.”

1979: The Strike

Salvador Bustamante, known as Chava, had followed his older brother, Mario, who had followed their father from Mexico into the fields of Southern California and then into the union hall. In the winter and early spring, they picked lettuce in the Imperial Valley, the southeast corner of California along the Mexican border, then followed the harvest north to Salinas when the weather turned too hot in the desert.Mario the firebrand and Chava the poet became union leaders, each elected to represent workers at his company.

“The union taught us not to be afraid,” Mario Bustamante said. “Before we became part of the union, we were afraid of the law, the police, the growers.”

The early successes were basic: an eight-hour day instead of harvest hours that began by the lights of trucks at 4:30 a.m. and ended when darkness fell at 9 p.m.

“That was one of the main advantages of having a union, to be able to put a limit on what the grower demanded,” Chava Bustamante said.

Such victories helped them win converts. “We were really able to instill faith in people. Not just hope: faith,” he said. “Our faith in the union.”

When the UFW launched what would be its last major strike in early 1979, the Bustamante brothers were part of the core group that helped Ganz run the action.

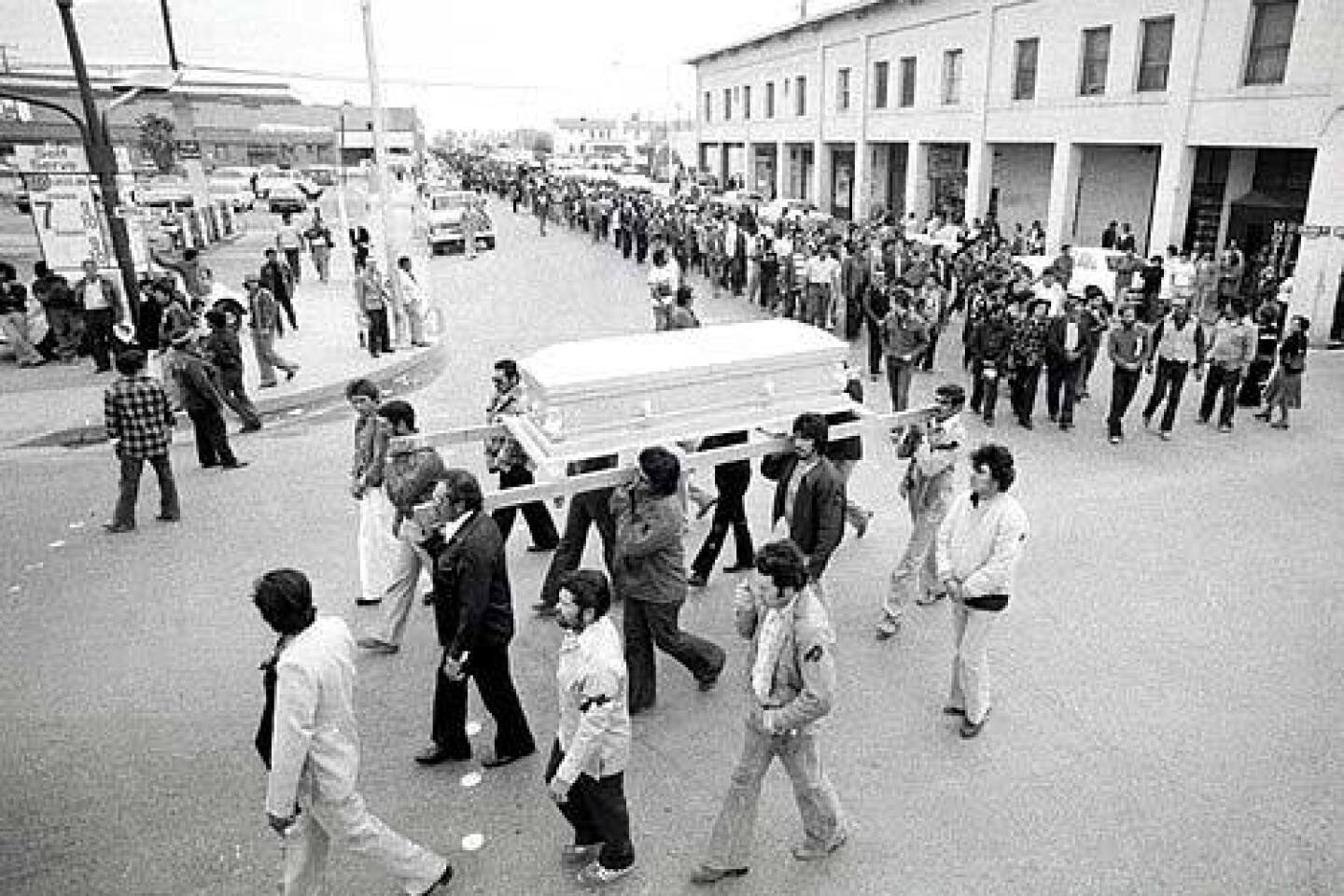

At first the strike was successful. Then, on Feb. 10, a striker named Rufino Contreras went into the fields to chase out strikebreakers and was shot and killed. Amid mourning and recrimination, acrimony escalated among UFW leaders.

By March, Chavez called a special meeting because executive board members were barely speaking to one another. He had only one suggestion: “We have to play the Game, clean ourselves up.”

Others, including his brother Richard, denounced the Game as destructive and doubted it would solve anything.

“I know it can,” Chavez responded. “I don’t know of any other thing; I don’t.”

Those who badmouthed the Game, especially Ganz, were undermining an unpleasant but useful tool, Chavez said: “Some people are afraid of being told things they’re guilty of. Some are willing to take it for the goddamn cause and some are not.”

The strike moved north into the Salinas Valley, following the harvest.

Ganz was stalling workers who wanted to expand the strike and stalling Chavez, who was pushing to end it. Workers devised slowdowns that varied from day to day: Plan Tortuga (turtle), go extra slow; Plan Canguro (kangaroo), skip over rows.

On the eve of the UFW’s convention in Salinas on Aug. 11, more than 6,000 farmworkers and supporters marching from two directions converged at a rally where Chavez and Gov. Jerry Brown gave fiery speeches and talked about a general strike.

In fact, Chavez had come to Salinas intent on shifting the union’s resources into a national boycott. At a secret meeting that night, he explained to the workers’ leaders that the UFW could not afford a strike.

“The union is broke. We’ve spent $2.8 million on this strike,” Chavez said. A boycott would increase pressure. “It takes more time, but it is easier to win. It is a sure win. In a general strike you aren’t as sure you will win.”

The farmworkers didn’t buy it. One by one, for more than 90 minutes, they articulated reasons to strike. If they were sent to boycott, they would lose their jobs and seniority. Workers had been eager to strike for months. If there was money to support a boycott, why not for the strike that workers were demanding?

“If we don’t do it, the high morale and all the desire they have had for so long to go on strike that morale will fall to the ground,” Chava Bustamante told Chavez. “We have to make a decision that we will have to live with forever.”

Workers who had been on strike for seven months would feel abandoned, his brother Mario said: “And with that, the faith and spirit that everyone had in us will be lost.”

Ganz ended the meeting after midnight, saying everyone was tired. The convention would endorse a boycott and a strike, concealing the dissension, and the group would reconvene. They never met with Chavez again.

“I think it was the worst thing you could do to a leader like him,” said Sabino Lopez, another farmworker who attended the meeting. “ To say, ‘Sorry, boss, we’re not going to boycott.’ ”

Within days, more workers went out on strike, without benefits. Chavez called a meeting at La Paz to plan the boycott; Ganz was running the strike and refused to go. The two did not speak for weeks.

“I didn’t feel I was part of the union leadership,” Ganz said.

Unusually hot weather accelerated the harvest and increased the pressure on growers, who began to settle on terms union leaders had only dreamt about: wages starting at $5 per hour, significant medical benefits and paid union representatives.

Chavez hailed the victories but shunned the celebration at a Salinas hotel. “We had the growers lined up at the Towne House, waiting to sign, and Cesar wouldn’t come,” recalled Cohen, the lawyer who handled negotiations.

Back in La Paz, there was a different celebration around the same time. A class of farmworkers had completed a 10-week English course. More than a hundred friends, family and residents of La Paz gathered for graduation and applauded a student slide show that concluded: “The union is not Cesar Chavez. The union is the workers.”

Minutes later, graduates and guests sat down to a celebratory lunch. Dolores Huerta rose and attacked the teacher, demanding to know who had put the students up to voicing such heresy.

The lunch was over before it began. Chavez fired two teachers later that day.

1980: The Paid Reps

The farmworker leaders had gathered at La Paz in May to discuss their new jobs when a jubilant young lawyer burst into the classroom to tell Cesar Chavez her good news: She had passed the bar.Like many, Ellen Eggers had become hooked on the UFW after working as a boycott volunteer during college. By the time she graduated from law school, the legal department she knew had been dismantled. Sorry to miss working for Cohen, Eggers was nonetheless happy to move to La Paz and work for the usual $5 per week.

Chavez interrupted the meeting and introduced Eggers to the farmworkers who had recently been elected as paid representatives. They gave her a round of applause.

Mario Bustamante and Sabino Lopez were among the dozen elected by their peers to work as full-time union representatives, paid by the growers to work for the UFW — in effect, the only UFW staff who earned salaries.

“They were the future,” Eliseo Medina said. “They were outstanding leaders.”

The paid reps, as they were known, worked closely with Ganz, who had nurtured their leadership through the strike. They tackled grievances against the companies and the union bureaucracy. They struggled to explain to workers that they had responsibilities as well as rights. They harassed La Paz about medical claims paid so slowly that workers were getting dunned by collection agencies. And they helped organize other workers, believing that was essential to protect the financial stability of companies that paid union wages.

After wildcat strikes began in the garlic fields of Gilroy, the paid reps won an unlikely ally.

Tramutola had worked for the UFW for 11 years and considered himself a loyalist. He knew others viewed him that way, some with suspicion because of his role in carrying out purges. He was wary of the paid reps, with their penchant for independence and their Salinas power base, until he saw them organize elections that summer.

“Knowing it worked totally changed my perspective,” he said. “They were the real deal. Their loyalty to Cesar was as great as anyone. It was working the way we had always hoped.”

When Tramutola was summoned to La Paz at the end of the season, he drove confidently in the union’s trademark Valiant, expecting to be quizzed about the election victories.

“In a second, I realized my time had come,” Tramutola said. “Cesar had a way of pursing his lips when he was angry. He looked at me and said, ‘Who are you working for?’ He said, ‘Are you taking your orders from Moscow? Only I will call elections.’ I said, ‘With all due respect, workers have the right to call for elections.’ ”

Tramutola resigned. He told others he did not want to be caught between Chavez and Ganz.

As questions about loyalty increased, so did forced resignations.

Gilbert Padilla had worked with Chavez and Huerta even before they formed the first farmworkers association back in 1962. A diplomat dubbed the Silver Fox, he had a gift for mimicry and making people laugh that served him well in negotiating compromises between workers and employers.

For some time, Padilla had found the changes in his longtime friend and mentor so puzzling that he asked others if they thought Chavez had gone crazy. Padilla was particularly outraged when Chavez scrapped plans for a clinic and service center in the Central Valley city of Parlier and turned the site over to a builder to make money jointly by selling houses.

“I knew Cesar was the man, el jefe, but I didn’t think the movement belonged to him,” said Padilla, who resigned as secretary/treasurer. “I thought it belonged to the workers.”

1981: The Confrontation

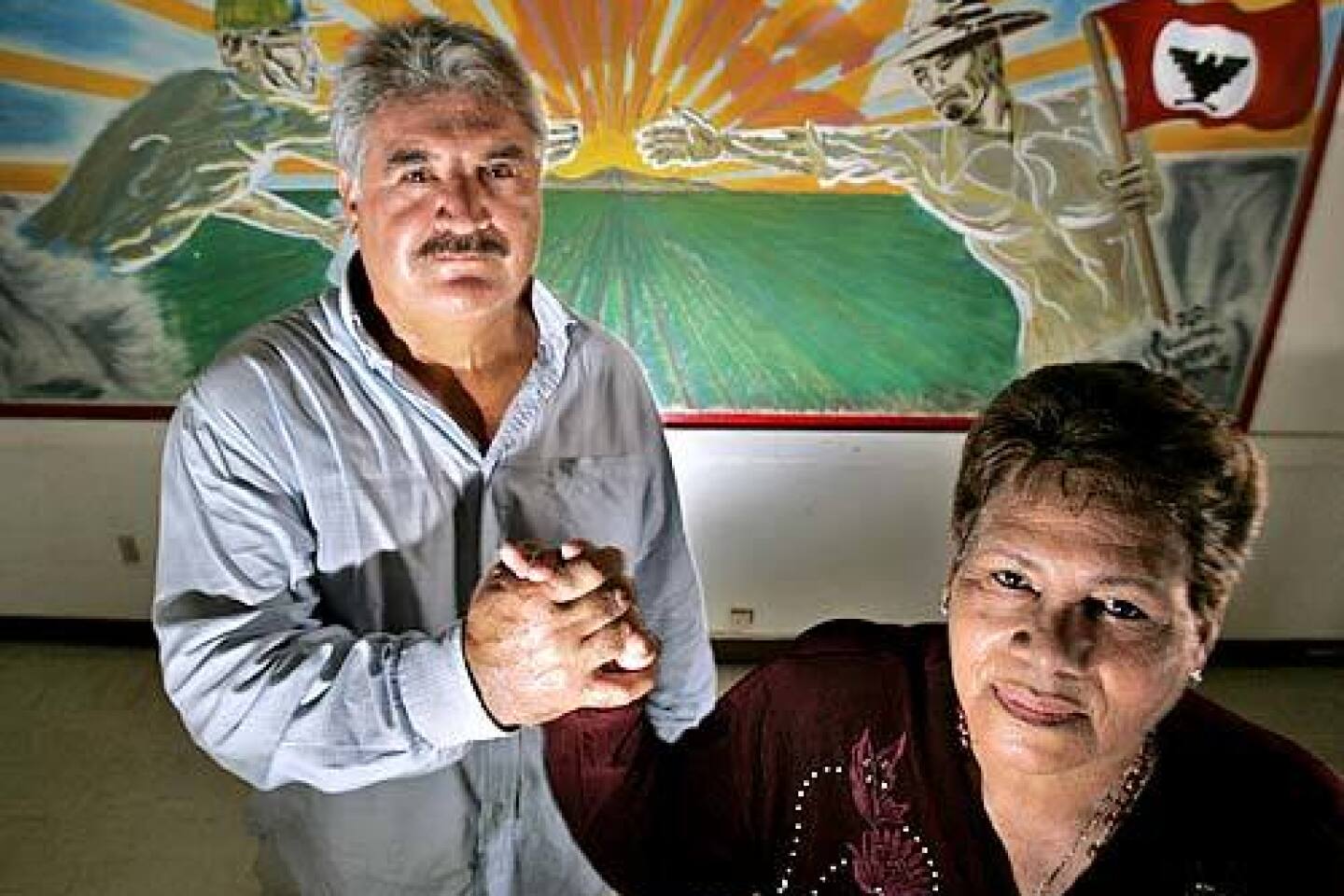

The farmworker leaders in Salinas who had faced off politely against Chavez two years earlier when he tried to curtail the strike no longer trusted the leadership in La Paz. The feeling was mutual.As the UFW convention approached, the challenge became more direct: The Salinas leaders decided to run candidates for the board. “There were no farmworkers on the board,” Mario Bustamante said. “There was a need for someone to be on the board who understood the problems in the field.”

They turned to Rosario Pelayo, a proud and fiercely determined farmworker with a warm smile and shy manner. Born in Mexico, she had worked in the fields since she was 8 and had followed her husband to California. She gave birth to 13 children, eight of whom survived, and began to volunteer with the UFW after the last was born in 1970. By 1973 she was getting arrested, by 1975 she was hosting Chavez at her home in the Imperial Valley, by 1977 she was president of the workers at her ranch.

“You always thought about the future of your children,” she said, recalling days that began at 2 a.m. with leafleting buses that workers took to the fields and ended with late-night organizing sessions. “You didn’t want what happened to you to happen to them.”

The campaign for the UFW board was as fierce and ugly as the elections between the union and the growers. Chavez dispatched board members, who spent almost $5,000 campaigning against the insurgents, painting them as dangerous radicals trying to depose Chavez at the behest of Ganz and Cohen. Both had left the union months before.

Huerta had often found fault with Ganz but had been unable earlier to shake Chavez’s confidence in his trusted aide. Then and now, she accused him of masterminding the Salinas insurgents’ campaign, a charge Ganz and the workers reject as patronizing and untrue.

“They were good organizers,” Huerta said about the paid reps, arguing they were manipulated by Ganz, who thought he should run the union.

On Sept. 5, Chavez opened the Fresno convention with a speech about “malignant forces” and then pulled off a parliamentary maneuver that effectively precluded a contested election for the board seats.

About 50 of the Salinas delegates walked out in protest. Chavez allies passed out leaflets calling the insurgents communists. Mario Bustamante broke the staff of his union flag in two.

The next day, Doug Adair, a grape picker and delegate from Coachella, rose to speak when Chavez asked for nominations.

Adair was working in the fields when he joined the UFW the day before the 1965 Delano grape strike began. He was a striker, a picketer, an aide in the legal office and an editor of the newspaper before returning to work at a Coachella vineyard. Pelayo had worked there, as had her sister. Adair liked her, and he thought the board needed someone who understood the workers’ problems and was willing to challenge Chavez.

“At that point, there was nobody on the board to disagree with him,” Adair said. “There was no connection between La Paz and the members in the field.”

Adair nominated Pelayo, but was ruled out of order because she had walked out the day before.

After the convention came the repercussions.

Adair’s wife was fired from her job as a nurse at the union-run health clinic. She was told, she said, that she was fired for “being married to the traitor.”

In Hollister, Cesar’s son Paul led picketing of the office of a legal assistance agency where Chava Bustamante worked.

“They’d come out to the fields and attack me and my friends,” Pelayo said. She returned to the Imperial Valley, never worked in the fields again and tried to shut out news of the union. “I didn’t want to know anything. It was great pain.”

In Salinas, Huerta led a campaign to unseat Mario Bustamante, who had served as president of the union workers at his company for seven years, and the other dissident leaders. When the workers stood by their elected representatives, Chavez fired them.

“They accused me of being a spy, being with the growers,” said Sabino Lopez. “I refused jobs with growers. I didn’t want to allow them to make the point. At the end, nobody wanted me. The union didn’t want me, the growers didn’t want me.”

Bustamante, Lopez and seven others sued, charging Chavez had fired them illegally because they were elected by the workers. Chavez countered with a $25-million libel suit.

The task of defending the UFW and its president fell to Ellen Eggers. She agonized. She convinced herself that Ganz was masterminding the plot, though she had doubts.

“I felt horrible,” Eggers said. “Here were these farmworkers who had assumed leadership positions, paid by the growers. Everyone had high hopes for them. And I was defending the guy who fired them.”

A decade later, Eggers would seek out Bustamante to apologize.

In 1982, a judge concluded that Chavez had acted illegally, because the reps were elected and not appointed. The victory was pyrrhic, since the contracts were expiring and many had lost their jobs.

Today Mario Bustamante runs a small taxi company in Calexico. He and Pelayo were recently denied UFW pensions because they fell short the necessary hours in their final year, after the fight occurred.

Chava Bustamante is a union leader again, the 1st vice president of a Service Employees International Union local representing California janitors and security guards.

Lopez still helps farmworkers in Salinas, as deputy at a nonprofit agency that finds housing solutions; he recently became the first farmworker on the board of the John Steinbeck Center.

“I’m part of the union. We did great things together,” Lopez said. The UFW experience, he said, transformed him from a shy immigrant with an elementary school education into a community leader. “No matter what happened, we’re part of the movement. We’re part of history. The union missed a really great opportunity to have farmworker leadership on top. There were really good people.”

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Activism timeline

Cesar Chavez rose to national prominence through his campaign to win higher wages, better working conditions and respect for farmworkers. Here are key points in the history of this movement:

1962: Chavez forms precursor to UFW, the National Farm Workers Assn.

1965: First grape strike starts in Delano and spreads in Central Valley.

1966: Chavez leads thousands of farmworkers on 340-mile march from Delano to Sacramento.

1967: First national grape boycott begins.

1968: Chavez’s first fast, to promote nonviolence. Fast broken with U.S. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy.

1970: Central Valley table grape growers, under pressure from boycott’s success, agree to sign contracts. Lettuce and vegetable strike starts in Salinas Valley after growers sign Teamsters contracts.

1973: Table grape growers also sign contracts with Teamsters, costing UFW most of its members. Strikes, violence, second national grape boycott follow; UFW, now part of AFL-CIO, drafts its first constitution.

1975: Agricultural Labor Relations Act signed, due to combined pressure of boycott, strikes, other protests. Union representation elections begin; Harris Poll reports 17 million Americans boycotting grapes in early 1970s.

1977: UFW signs pact in which Teamsters agree not to try to organize farmworkers.

1979: Lettuce and vegetable strikes start in Imperial, then Salinas valleys. By fall, UFW signs contracts with record wage increases, 50% over three years.

1984: Third grape boycott starts, focused on pesticide use; has little effect and ends in 2000.

1988: Chavez engages in final fast, tied to pesticide boycott.

1993: Chavez dies; son-in-law Arturo Rodriguez takes over union.

Sources: Times reporting

Los Angeles Times

*

About This Series

Quotes and historical references are drawn from letters, board minutes, memos and statements and tape recordings made during the 1970s and 1980s. The material is housed in the UFW archives at the Walter P. Reuther Library at Wayne State University in Detroit.

Sunday: The UFW betrays its legacy as farmworkers struggle.

Monday: The family business: Insiders benefit amid a complex web of charities.

Today: The roots of today’s problems go back three decades.

Wednesday: A UFW success story — but not in the fields.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.