How L.A.’s Iranian American community is reacting to President Trump’s travel ban

Marzieh Moosavizadeh landed at Los Angeles International Airport on Saturday expecting to be welcomed in the arms of her grandson who had flown from Phoenix to meet her flight.

Instead, the 75-year-old matriarch was pushed in her wheelchair into a waiting room with a couple dozen other passengers.

About 6 p.m., two hours after her flight landed, an attendant offered her a cellphone to call her grandson.

Passengers were afraid to talk to one another, Moosavizadeh said.

“Most of them, they thought they were going to get deported,” she said, through her son, translating by telephone.

The confusion and consternation after President Trump’s order barring the entry of citizens from seven predominantly Muslim countries has hit an established community of Southern California immigrants whose flight to this country was precipitated by the rise of a Muslim theocracy.

Moosavizadeh is among those who remained in Iran as relatives fleeing the Islamic Revolution flocked to the United States. Now she visits almost every year.

She has never had an arrival like this.

Taking her to a room, customs officers asked her when she last visited the U.S., who she lives with in Iran and where she gets her income.

Meanwhile, in Phoenix, her sons frantically refreshed news articles and peppered her grandson, Siavosh Naji-Talakar, with questions he couldn’t answer. Huddled among throngs of boisterous protesters demanding the detainees be released, Naji-Talakar could do little but wait.

Moosavizadeh’s name was among the last ones called, about 1 a.m.

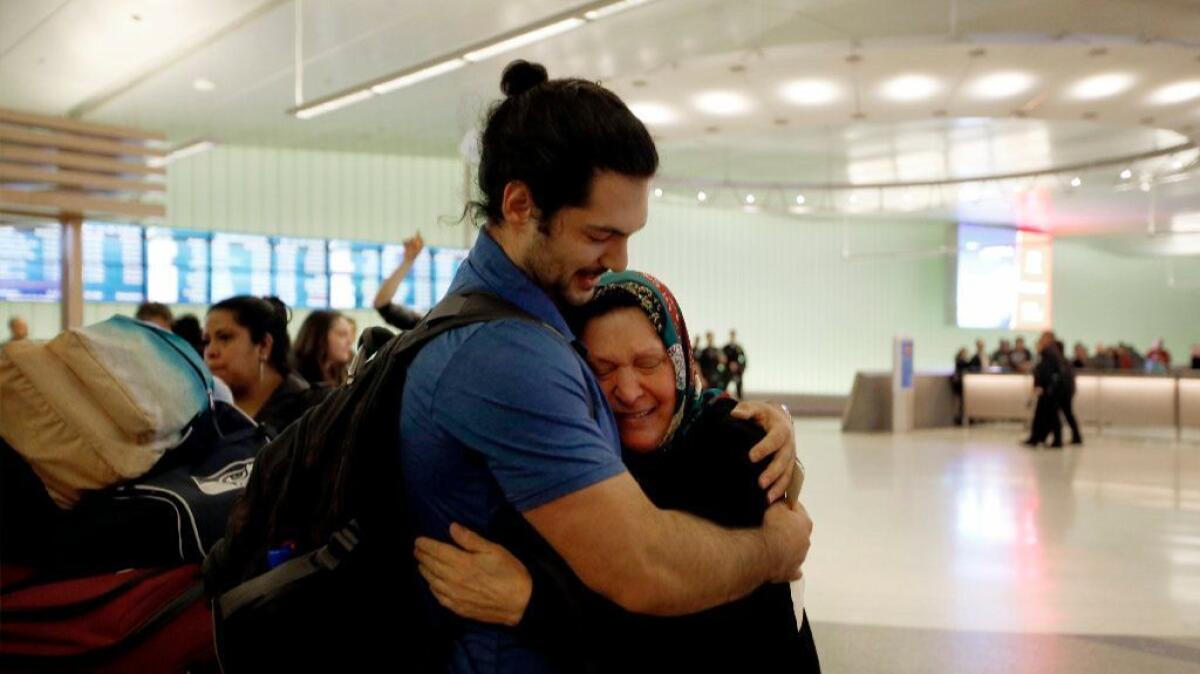

When Naji-Talakar saw her, he bolted.

“I pushed people out of the way, I was like, ‘Get out of my way!’” he said. “I ran up to her and gave a big old hug.” Finally, she said, she was “released from prison.”

Of the 87,000 people of Iranian ancestry who live in Los Angeles County, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, most trace their roots in this country to the Islamic revolution that overthrew the Western-oriented rule of Shah Reza Pahlavi in 1979. They have formed prominent communities in well-to-do neighborhoods, including Westwood and Beverly Hills.

And despite the deep political differences that still exist between the two nations, family connections persist, and thousands of Iranians travel back and forth each year.

Among them are Jews and Christians as well as followers of lesser-known faiths such as Zoroastrianism and Bahai, said Shakeel Syed, spokesman for the newly formed Muslim-Latino Collaborative.

That organization formed on the day of Trump’s inauguration to unify the response of two groups that were being demonized by the president-elect.

Now, Syed said, Trump’s order is producing the same kind of bond among Iranians of different backgrounds.

At the same time, it is drawing the less religiously oriented Iranian Muslims closer to the immigrants from countries such as Iraq and Syria.

“All of these folks are cultural or marginally practicing Muslims now standing shoulder to shoulder with the practicing Muslim community from Iraq and scores of other Muslim communities in Southern California,” Syed said.

That unifying sentiment rose in Ava Lalezarzadeh’s voice as she and her parents finished breakfast Sunday morning at the Pink Orchid Bakery, one of many Persian shops that dot a stretch of Westwood Boulevard.

The 18-year-old UCLA freshman’s mother and father fled Iran as teenagers in the late 1980s, in fear of the persecution for being Jewish.

Lalezarzadeh’s mother worked her way through Pakistan and Vienna before gaining legal entry to the U.S. Her husband came on a visa and applied for political asylum when it expired. Both became U.S. citizens when their daughter was in elementary school.

“If this ban had taken place when my parents needed help, I wonder: Would we be here today? Would you even be alive?” Lalezarzadeh asked, turning to her mother.

“I think about the Syrians who are going through such turmoil in their country and how you guys were lucky enough to be able to come here. They don’t have that.

“They’re us right now,” Lalezarzadeh continued. “And it’s just so unfortunate.”

Her father, Fariborz Lalezarzadeh, 44, is a surgeon at a hospital in San Bernardino, where victims of the deadly 2015 terrorist attack were taken for treatment. He said he understands the desire to prevent another one.

But he believes Trump’s ban unfairly targets too many people and ignores other countries with links to terrorism.

“I understand the background of why he’s doing this. I’m just not sure if this is the best way of doing it,” he said. “You’re going to hurt a lot of innocent people in the process.”

I understand the background of why he’s doing this. I’m just not sure if this is the best way of doing it.

— Fariborz Lalezarzadeh, 44

But not all the Iranian Americans spending Sunday on Westwood Boulevard had qualms about Trump’s travel ban.

In one hair salon, some women were for it.

“We don’t want any terrorists in this country,” one woman said as a stylist finished her hair.

“You’re right,” chimed in another, who later declined to give her name. “We came here as immigrants as well, but we do all the steps. We did it the right way.”

The stylist, Minoo Toovia, saw more nuance. She immigrated to the U.S. from Iran 35 years ago, she said, and became a citizen “a long time ago.” She thought of the students in other countries who now may not be able to come to America, others who live abroad but want to visit their families here.

“Some people are innocent. Some are good. Some bad. You can’t mix them all together,” she said. “It’s not fair.”

Back at the bakery, Danny Shoumer and Fred Gal also expressed their support of Trump and his stance on immigration. The men, who are in their 60s and have been friends since their childhood in Iran, both immigrated to the U.S. in the 1970s and later became citizens.

Shoumer came to the U.S. for college, then briefly returned to Iran as the revolution there began. He got a green card, returned to the U.S. and became a citizen in the late 1980s.

Putting aside concerns about terrorism, Schoumer said he worked hard to make a life for himself in America and believes other immigrants should do the same.

“I came here, went to college, busted my butt every night at a restaurant,” he said. “Now a bunch of people are going to come here, use our tax money and do nothing.”

Across the street, Dariush Zarang unlocked the door of another Persian restaurant, the Farsi Cafe, as it opened for business. The 46-year-old assistant manager said that a co-worker who went to visit his mother in Iran was now stuck abroad, in limbo despite holding a green card. The co-worker was supposed to return to the U.S. two days ago, Zarang said, but was instead stopped in Istanbul.

“People are confused. Even the airports are confused,” Zarang said. “We don’t know what’s going on.”

Zarang immigrated to the U.S. as a refugee nearly two decades ago, fleeing religious persecution in Iran because of his Bahai faith. He became a citizen a few years later.

He understands — and supports — the idea of exploring the backgrounds of people who come to the U.S. But he doesn’t believe people should be stopped or vetted just because they’re from a certain country. Someone’s ideas, good or bad, matter more than where they are from, he said.

“I don’t think it’s fair,” he said.

alene.tchekmeydian@latimes.com

ALSO

Protesters block traffic at LAX as thousands rally against Trump travel ban

Travel ban is the clearest sign yet of Trump advisors’ intent to reshape the country

When Muslims got blocked at American airports, U.S. veterans rushed to help

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.