Court backs disclosure of officers’ names in shooting cases

Reporting from San Francisco — Police agencies generally must tell the public the names of officers involved in shootings, the California Supreme Court decided Thursday.

The state’s highest court, in a 6-1 vote, rejected blanket policies by a growing number of police agencies against disclosure. The court said officers’ names can be withheld only if there is specific evidence that their safety would be imperiled.

“If it is essential to protect an officer’s anonymity for safety reasons or for reasons peculiar to the officer’s duties — as, for example, in the case of an undercover officer — then the public interest in disclosure of the officer’s name may need to give way,” Justice Joyce L. Kennard wrote for the majority.

“That determination, however, would need to be based on a particularized showing.”

The decision is likely to make it much more difficult for police agencies to withhold the names of officers involved in on-duty shootings.

“Vague safety concerns that apply to all officers involved in shootings are insufficient to tip the balance against disclosure of officer names,” Kennard wrote.

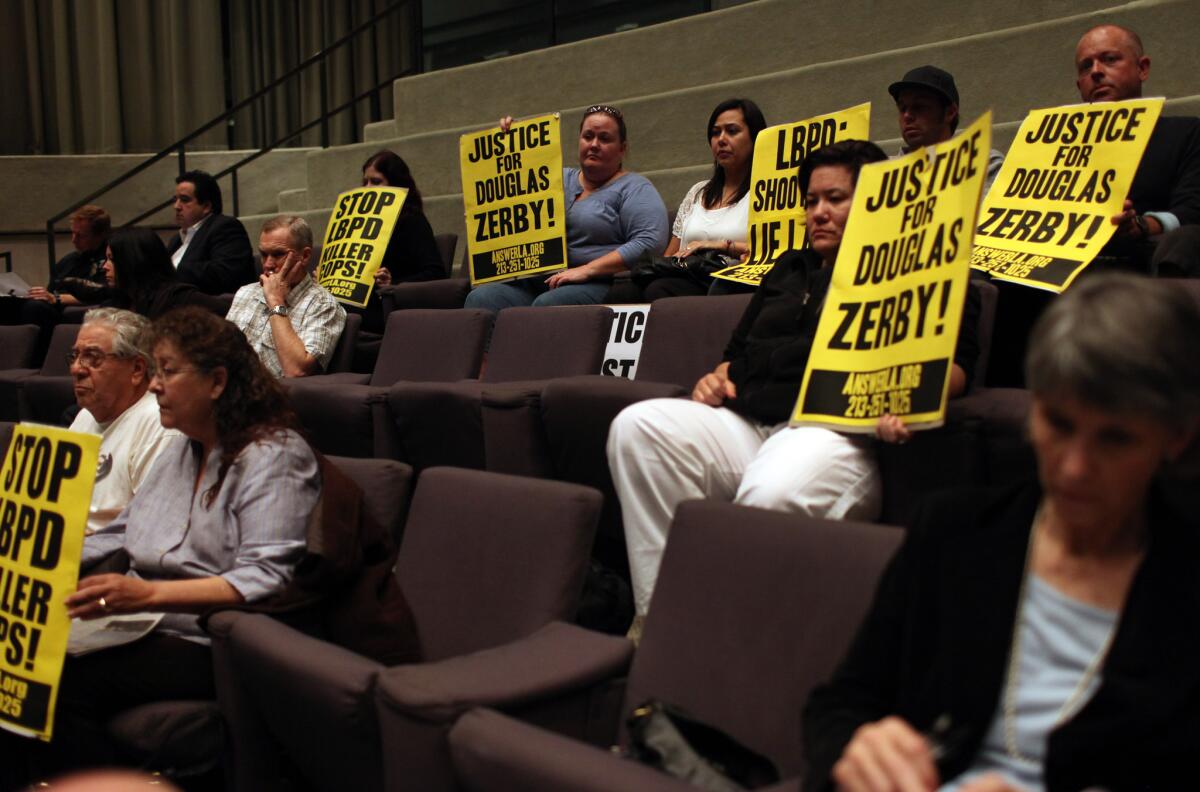

The case stemmed from an effort by the Los Angeles Times to obtain the names of Long Beach police officers involved in the fatal shooting of Douglas Zerby, 35, in 2010. The officers mistook a garden hose nozzle Zerby was holding for a gun.

Times reporter Richard Winton made a California Public Records Act request asking for the names of the officers who shot Zerby and the identities of all Long Beach officers who had been involved in on-duty shootings in the prior five years.

The Long Beach Police Officers Assn. went court to prevent the city from disclosing the names, citing the confidentiality of personnel records and a need to protect officer safety.

The police group and the city of Long Beach, joined by other California law enforcement agencies, argued that revealing the identities would endanger officers and their families because home addresses and telephone numbers can be obtained on the Internet.

The Times, backed by other media and California ACLU groups, countered that the public had the right to know the identities of officers who use lethal force.

Los Angeles prosecutors eventually revealed the name of the officers involved in Zerby’s shooting in a report that exonerated the police. The officers had been summoned by a neighbor who said there was an intoxicated man with a gun outside a Belmont Shore apartment complex.

A federal jury later awarded Zerby’s family $6.5 million after concluding that the two officers had behaved recklessly when they shot Zerby.

An autopsy showed that Zerby was shot 12 times.

Kelli L. Sager, who represented The Times in the case, said police agencies would have a “difficult burden to meet” if they try to withhold officer names.

A refusal to disclose would have be justified by “particular things about an individual case” and “unusual safety concerns beyond the recognized concerns about officer safety in general,” she said.

“This is a matter of extreme public importance, and The Times has been litigating this issue with police departments throughout the state for many years,” Sager said.

Assistant Long Beach City Atty. Michael Mais said the city was unlikely to ask the court to reconsider the ruling because it would probably be futile. He said Long Beach would now release names in all cases except when it can show a “particularized, credible threat” against an officer involved in a shooting.

“It would be a situation where someone is making a direct threat to an officer immediately following a shooting,” Mais said. “If someone says, ‘I am going to go after that police officer when I find out who he is, and I am going to harm him and his family,’ the burden would be on the city to show that is a real threat,” Mais said.

The Los Angeles Police Department already has a policy to release the names of officers involved in shootings unless safety is at issue. In the majority of cases, the officers’ names are provided.

But Lt. Steve James, president of the Long Beach Police Officers Assn., called the ruling “very concerning.”

“In today’s Internet age, we believe that releasing the name of an officer is tantamount to releasing the officer’s home address and other personal information,” James said.

“What happens when we receive a credible threat after the name of an officer is released?” he said. “We can’t get that information back.”

In a dissent, Justice Ming W. Chin said the ruling would “impose an obvious and substantial burden on law enforcement agencies that want to protect their officers.”

“Absent a showing of some greater public need for the information, we should allow law enforcement agencies to protect the very officers who are out there every day protecting us,” Chin wrote. “They deserve at least that much for their brave service.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.