This is what it’ll take to prevent another warehouse fire like the Ghost Ship

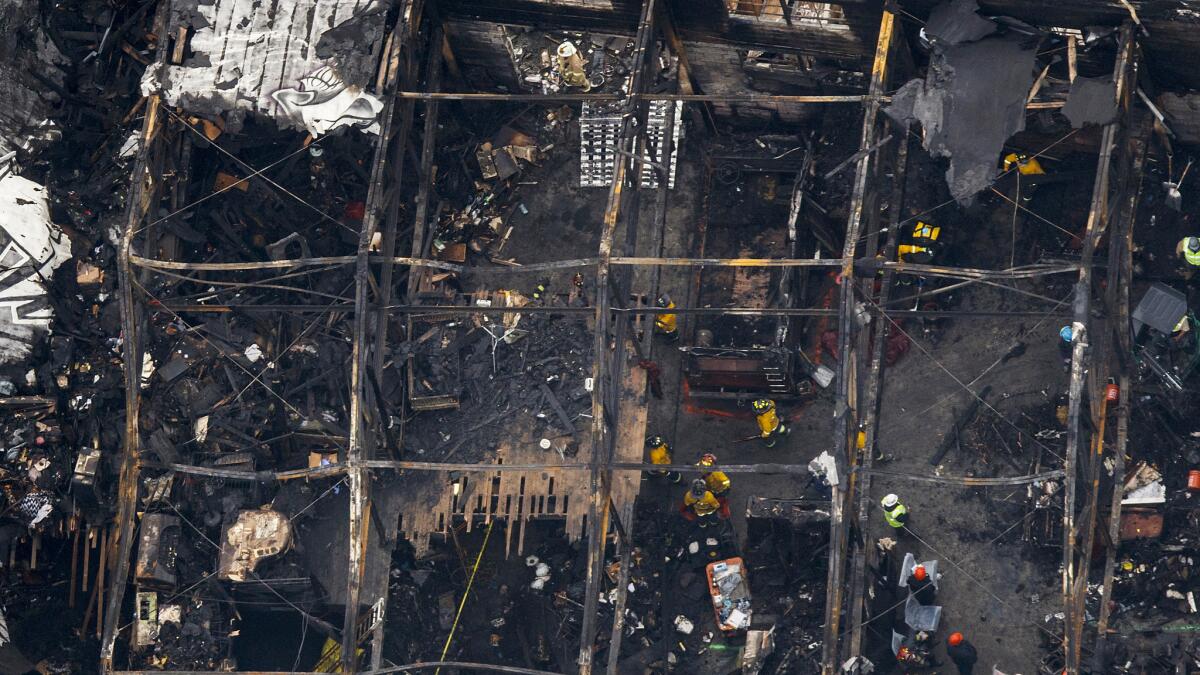

Reporting from OAKLAND — The trail of the catastrophic Ghost Ship fire was littered with errors: Safety complaints lingered without reply, the warehouse was illegally converted into residential units, and former residents said the electrical system was shoddy.

The building’s history was not unique, a fact that has prompted officials in several cities to declare a crackdown on warehouse conversions.

Inspectors in Bay Area cities have opened investigations into dozens of buildings, and the Los Angeles city attorney has sued the owner of a warehouse illegally converted to lofts. Denver authorities recently evacuated a building that wasn’t zoned for residents.

But truly cracking down on illegal converted warehouses is going to take time, detective work and likely more resources from municipal governments. Many operators of these warehouses work under the radar, avoiding city permits that would prompt scrutiny from inspectors.

One Oakland official with knowledge of the Ghost Ship investigation estimated that there were 20 to 50 other illegally converted warehouses in the city alone, though none likely as dangerous as the warehouse where 36 were killed this month in the worst fire in modern California history.

The source, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said some firefighters at the station level know about many of the converted buildings. But until the fire, the city had not made any coordinated effort to gather the information and take action, the source said.

Oakland developer John Protopappas agreed the city is “replete” with warehouses zoned for commercial use but whose owners rent out space to residents. Under the law, the owners or operators must make costly improvement to the buildings — including the electrical and fire-safety systems — if they use the warehouses as housing.

By making the conversion without city knowledge, they avoid having to make upgrades but often put their tenants at risk.

“To legalize use is very hard and difficult. They say: ‘Forget it. I’m not going to do it,’” Protopappas said. “Now you’re looking over your shoulder every time something occurs.”

And many residents take those risks because of the housing shortage and the relatively cheap rent these buildings offer.

Los Angeles City Attorney Mike Feuer said it’s a complicated problem that will involve putting more resources into finding the buildings and addressing the rental crunch that has pushed people into substandard housing.

“There’s a broader issue: How is the city going to grapple with other commercial properties that house tenants?” Feuer said. “The city must continue to do a better job of increasing our stock of affordable housing.”

Feuer’s office has sued the owner of one warehouse illegally converted into lofts and asked the court to put the building into a receivership.

Feuer said a notice was to be posted to tenants about the dangers they face inside the property at 931 East Pico Blvd., in the Fashion District. The warehouse is essentially a vast open space with an freight elevator. Inspectors, according to the city, found that the fire doors on the elevator didn’t work.

“The ceiling in some lofts is nothing more than wooden floors above,” noted the lawsuit. According to an inspection, furniture filled a fire escape and exits were obstructed.

Last week, the owner of the building, Morad “Ben” Neman, was charged with several misdemeanors, including constructing residences that lacked smoke alarms and accessible fire escapes. Neman faces up to $9,000 in fines and 4 1/2 years in jail. His attorney said the building poses no danger and that the city attorney’s court filings were only about political ambitions.

The recent filings came after a year of violations, including inadequate fire systems and illegal interior conversions, officials alleged.

Bradley Brunon, Neman’s attorney, said the building poses no danger and that the judge during Monday’s hearing declined to immediately put it into the hands of a receiver.

“You can walk anywhere within 10 minutes of the place and find buildings that are clearly dangerous,” Brunon said. “This is an outgrowth of the Oakland fire and certain political ambitions.”

Brunon said he walked through the building last week and found a clean, well-lighted structure.

It’s unclear how difficult it would be to find additional illegally converted warehouses if municipal leaders made it a greater priority. In Oakland, there is growing evidence that the city received numerous complaints about the Ghost Ship in recent years but did not get inside the building.

Officials revealed last week that no building code enforcement inspector had been inside the warehouse in at least 30 years, despite the fact that the building and its adjoining lot had been the focus of nearly two dozen building code complaints or other city actions.

The address of the warehouse was not found on the fire marshal’s inspection system, raising more questions because the Fire Prevention Bureau is required to conduct annual inspections of all commercial buildings and multifamily residences.

Officials have not determined the exact cause of the Ghost Ship fire, and they have been focusing on the building’s electrical system. Former residents described a maze of exposed wires and extension cords running through the warehouse.

In the wake of the fire, city code inspectors in Oakland and San Francisco opened numerous investigations into questionable buildings.

Among the targeted properties was an old warehouse on Magnolia Street dubbed by some residents as “the Death Trap” — a label they said a city inspector used to describe their home. Oakland records show that in 2011, city inspectors found blight in the exterior of the warehouse but “could not verify” unpermitted alterations inside. The complaint file remained open without action until 2014.

Former resident Brent Bucci, a light show artist who now lives in Los Angeles, said tenants were told they would have to leave. But evictions never occurred, and some residents continued to live there, he said.

City inspectors returned to that warehouse Thursday investigating a habitability complaint, taking pictures of its exterior. Records filed later in the day showed they found the property in violation of city codes.

Three blocks away, inspectors investigated a complaint of illegal residents at an address last permitted for use as a hydroponics office. Past inspections of the building were stymied after city personnel could not gain entry. It’s unclear whether they got into the building last week, but officials did serve the owners with a violation notice.

The crackdown has prompted mixed feelings in Oakland.

On Monday, a group of Oakland activists pulled together a rally, demanding a moratorium on evictions.

“Honor the dead! Fight for the living!” they wrote in an online call to action. “Eviction is not a solution to a symptom of gentrification.”

Serna and St. John reported from Oakland; Knoll and Winton from Los Angeles. Times Staff Writer Phil Willon contributed to this report.

ALSO

Victims of the Oakland warehouse fire: Who they were

‘We’re all kind of searching.’ Mourners make pilgrimages to the Ghost Ship from Oakland and beyond

Refrigerator ruled out as cause of Oakland fire that killed 36; no evidence of arson

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.