Neel Kashkari says his diverse skills prepare him to serve as governor

Neel Kashkari’s career has taken him from engineering to investment banking to managing the federal government’s $700-billion bailout of Wall Street, overseeing stock funds and running for governor — all by age 40.

What others might view as a young man’s wandering ambition, Kashkari sees as the accumulation of skills needed to unseat incumbent Gov. Jerry Brown.

“I think I’ve taken elements from different parts of my life and brought it all together,” said Kashkari, making his case in a recent interview on the patio of a gourmet sandwich shop in downtown Los Angeles.

“I am really good at parachuting into a new situation and figuring it out and working with people and getting stuff done,” he said.

People who know Kashkari, a Republican who lives in Laguna Beach, describe him as bright, energetic, goal-oriented and direct. Voters will decide if those traits and his varied resume qualify him to govern.

At the moment, it’s a big if.

The 76-year-old Brown, a Democrat seeking his fourth term, is expected to easily place first in the June 3 primary, from which the top two finishers will advance to November’s general election. Polls have shown Kashkari far behind Brown and trailing Tim Donnelly, 48, a conservative and controversial Republican assemblyman from San Bernardino County.

Unlike his opponents, Kashkari, a fiscal conservative and social moderate, has never held elective office. He may be best known for his stint as head of the Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, during the national financial crisis. But most of his experience is in private-sector finance, where he amassed personal wealth he has estimated at less than $5 million.

Kashkari, who has an older sister, was born in northeastern Ohio, where his parents settled after emigrating from India in the 1960s. His father taught electrical engineering at the University of Akron, and his mother was a pathologist at a hospital. Both are now retired.

He bagged groceries and mowed lawns as a kid, attended a private prep school near his hometown of Stow, and then earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mechanical engineering from the University of Illinois. He then took a job at TRW in Redondo Beach, where he designed space-telescope components.

After about two years, Kashkari said, he faced the choice of devoting decades of his life to research or trying something different. He opted for the latter, took out a $100,000 loan and enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of business.

“Neel stood out as clearly one of the best students I had that year,” said Anjani Jain, a former vice dean. “He had a sense of purpose and a quiet sense of confidence about his ability.”

Kashkari, who earned his MBA in 2002, sought a career that melded engineering and business. He landed at Goldman Sachs’ technology banking group in the Bay Area, and for the next four years worked with start-ups and small software and Internet companies.

Liz Huebner, a former chief financial officer at Getty Images, a Seattle stock-photo agency, said that, among other things, Kashkari helped arrange financing for a major acquisition by the company. He also became a trusted strategic advisor, she said.

“He just had a very good way of explaining alternatives and instilling confidence without sort of cramming something down people’s throats,” she said.

Kashkari rose to vice president, a position held by thousands, two rungs below partner in the Goldman hierarchy.

“Vice president sounds like a big deal,” the candidate said, smiling, “but in the context of investment banking, vice president is pretty darn junior.”

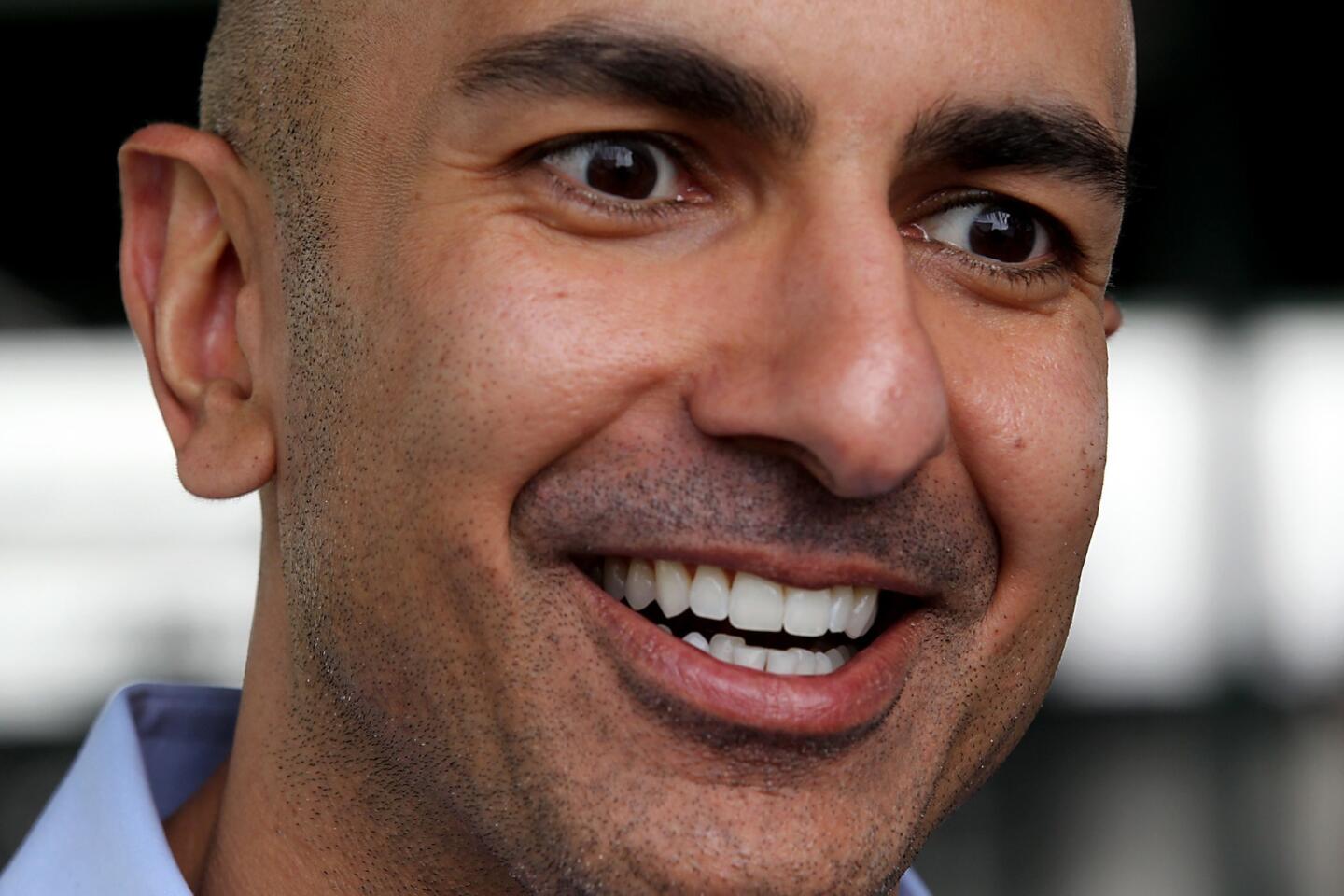

Kashkari’s intense appearance — shaved head, piercing dark eyes, heavy brows — belies a generally relaxed, upbeat demeanor. During the interview he took a brief timeout to deal with another pressing matter: a Web video starring his two 135-pound Newfoundland dogs, Winslow and Newsome.

The dogs have their own Twitter accounts and live with Kashkari in a rented oceanfront house. He is divorced but still owns a home near Lake Tahoe with his former wife.

Kashkari said he became interested in public service as a teenager, when his father received an award from President George H.W. Bush for his research on hunger and poverty in Africa and India.

After four years at Goldman Sachs, Kashkari applied for a White House fellowship but didn’t make the final cut. Two months later, however, when Goldman CEO Henry Paulson Jr. was named Treasury secretary, Kashkari asked him for a government job.

“I don’t care if you want me to lick envelopes,” he remembers telling Paulson, who hired him as a staffer in 2006.

“People at Goldman thought I was insane,” Kashkari recalled. “And I said, ‘You’re insane; this is a once-in-a-lifetime chance.’ ”

Kashkari, who said he tends to get “deep, deep into the weeds on policy,” worked on alternative energy and other issues before Paulson tapped him during the financial crisis to run TARP, in October 2008. He oversaw the bank bailout until the following May, when he stepped down early in the Obama administration.

During a six-month post-TARP respite, Kashkari said, he sent out feelers to financial institutions. In late 2009 he was hired to build a global equities business at Newport Beach-based Pacific Investment Management Co., one of the world’s largest bond-investment houses.

His appointment raised some eyebrows on Wall Street. Such a position would typically go to someone with a deep background in managing stock funds, analysts said.

“It was an odd choice for Pimco to bring him in,” said Karin Anderson, a senior analyst with financial research firm Morningstar Inc. “Not being an investor himself or having run money for others, it just seemed like an unusual thing.”

Kashkari brushes that notion aside, countering that his job was to hire teams of investment experts, not to pick stocks or manage portfolios.

“Could you be the CEO of a hospital without being a doctor? Sure,” he said. “I was leading a process and leading people, as opposed to saying…, ‘This is how we should invest in Apple.’ ”

Of Pimco’s $2 trillion in managed assets, only a fraction — about $10 billion — are stock funds. They were designed to perform better in down markets so have not fared well in the bull run of recent years, analysts said: Funds launched under Kashkari’s tenure from 2010 through 2012 have significantly lagged their peers.

Michael Castine, a partner with executive search firm Ridgeway Partners, said it probably became clear to Kashkari that bonds would always be “the lead dog in the race” at Pimco, with stocks a distant second in importance.

“He probably saw the writing on the wall and decided to run for office,” said Castine, who got to know Kashkari during his time at Pimco. “I guess with Neel it is go big or go home.”

Kashkari clearly expected to go big in the race for governor. He talked of raising several million dollars before the primary, to buy television ads aimed at state voters. But he has fallen well short of that goal, despite significant contributions from Paulson, Paulson’s wife and others in the financial sector.

Kashkari recently pumped $2 million of his own money into his campaign, raising his self-funding total to nearly 40% of his wealth. Around the same time, his ads hit the airwaves.

In the interview, Kashkari expressed pride in his work at Pimco, insisting that his decision to leave in 2013 was driven only by his desire to return to public service.

“Running for governor fires me up every day,” he said. “Going on TV and talking about the outlook for the stock market? That didn’t fire me up.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.