Beige plague

ELKO, NEV. — Around every bend of the dirt road, Tom Warren recites another name, another date. The Sheep, the Amazon, the Winters, the Suzie. The list goes on and on.

It is a chronicle of loss, of wildfires ravaging one of America’s mythic landscapes, the sweeping, lonely sagebrush country of the West.

On mountainside after mountainside here, in valley after valley, the richly textured, muted green of sage has yielded to a monotonous, dried-out sea of dirty-blond cheatgrass.

The annual grass, a tough native of Eurasia, is fueling a devastating cycle of fire that is wiping sage from vast stretches of the Great Basin and, with it, an ancient ecosystem that is home to the pronghorn antelope, strutting sage grouse and other prized wildlife.

The Great Basin, which swallows most of Nevada and reaches into parts of Utah, Idaho, Oregon and California, is the epicenter of a plague of wildfire driven by the spread of nonnative plants. Some of the biggest conflagrations in the nation over the last decade have burned in this cold high-desert region.

“The Winters fire took out that mountain and went on for 20 miles,” says Warren, a rehabilitation manager for the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. He is glancing out the window of a government SUV as it bumps across the backcountry of northeastern Nevada.

He points out the 150,000 acres charred by the Sheep fire. It consumed islands of shrub that had survived an earlier blaze. Not even the skeletons of sage are left.

It’s like that across much of the 135-million-acre Great Basin.

“If something hasn’t burned yet, it’s waiting to burn,” said Steve Knick, a research ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Idaho. “Just the rapidity with which the landscape has changed is unbelievable.”

Grassy aliens carpet the ground. They dry out quickly and burn in an instant. When lightning strikes a bed of dead cheatgrass, it’s like dropping a match into a lake of kerosene.

Country that used to burn every few decades -- or once a century -- is burning every few years.

Cheatgrass fed the largest blaze in Utah’s recorded history, last year’s Milford Flat fire. It galloped at freeway speeds across 363,000 acres of rangeland, incinerating hundreds of cattle.

In the Mojave and Sonoran deserts, where lightning fires historically stayed small and isolated because there wasn’t much to burn, flames are following the spread of tassel-headed red brome.

In 2005, after high rainfall produced a luxuriant crop of brome and other exotic grasses, 1 million acres of the Mojave were charred.

Air pollution may be abetting the invaders. Researchers have found that high nitrogen deposits are fertilizing nonnative grasses in parts of Southern California. In southern Nevada, experiments have shown that brome thrives at elevated levels of carbon dioxide expected in the atmosphere by mid-century.

Nowhere is the grim mating of wildfire and invasive grasses more evident than in the huge Elko District of the Bureau of Land Management in northeastern Nevada. This endless country of jagged mountains and gently sloping basins is burning with a regularity that is brutal and on a scale that is staggering.

In 2006, 950,000 acres of the district were scorched -- about the size of Rhode Island and roughly a tenth of all the wildlands that burned in the entire United States that year. Last summer, fire raced across nearly 600,000 acres, an area bigger than Orange County.

The blazes can be traced by color. If the land is tan, it has burned and turned to a thick mat of cheatgrass, ensuring that it will burn some more. Whether cruising down Interstate 80 to Reno or dodging the washboards on a primitive road in the middle of nowhere, it’s hard to escape that khaki stain on the landscape.

Since Warren started working in the 11-million-acre Elko District in 1984, it has lost more than a fifth of its sage habitat to fire. Courtship grounds for the sage grouse, crucial winter range for mule deer and browse for pronghorn antelope have all been vaporized.

The Elko District has spent $40 million since 1999 reseeding and rehabilitating the charred lands, with limited success. “It’s a system where it’s easier to lose things than it is to get them back,” Knick said.

Rooted in nostalgia

From Frederic Remington paintings to Gene Autry songs and John Wayne movies, the cultural imagery of the West is steeped in North American sagebrush -- Artemisia tridentata and relatives.

Cowboys bed down in it. Wagon trains roll past it. The sun sets on its rolling expanses.

In “The Call of the Wild,” the early 20th century poet Robert Service asks:

Have you wandered in the wilderness, the sagebrush desolation,

The bunch-grass levels where the cattle graze?

Have you whistled bits of ragtime at the end of all creation,

And learned to know the desert’s little ways?

Jon Griggs started working as a cowboy on the Maggie Creek Ranch west of Elko 17 years ago. For the last decade, he has been manager.

“My favorite smell is sagebrush after a rain,” Griggs says. “It’s kind of musky, fresh, almost bitter. . . . It pretty much represents what I love. I love the cattle operation I’m on and the country we’re in and the place I get to raise my family.”

Lately it is the smell of burning sage that has wafted across Maggie Creek Ranch.

Last year the Redhouse Complex fire hit. The year before, it was the Suzie. “It started on an afternoon about 2 o’clock with several lightning strikes, and by 9 o’clock the next morning it was 30,000 acres,” Griggs recalled.

He tried to stop the Redhouse by himself. “I was there with a dozer, when it was 20 or 30 acres. But it moved so fast I couldn’t get around it.”

Between the two blazes, Griggs estimates, 80% of the ranch’s public and private grazing lands has burned in the last two years, inviting more cheatgrass.

A few hours’ drive north, just outside of Boise, Idaho, Mike Pellant and his colleagues at the Bureau of Land Management are waging a Sisyphean campaign against fire and cheatgrass in the Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area.

Pellant is coordinator of the Great Basin Restoration Initiative, a government effort launched in 1999 after a chunk of the basin bigger than Delaware burned in 10 days. The program sponsors native plant research and promotes reseeding.

When Pellant started working at Snake River in 1981, the conservation area was mostly sage. Now it’s mostly cheatgrass. In the last 15 years, 70% of it has burned at least once.

Near a road, Pellant walks into a remnant patch of Wyoming big sage, the dominant sagebrush of the Great Basin.

The woody gray-green-leafed shrub, about 3 feet tall, provides wildlife with a kitchen and bedroom: food and cover from snow and searing sun. The moss-like crust spreading between the plants acts like a lawn, absorbing moisture and holding the soil in place. The low-growing, high-protein winterfat shrub scattered around the sage offers another level of food and shelter.

In contrast, a cheatgrass landscape is about as ecologically rich as a parking lot. “It’s rare to even find lizards,” Pellant said. “Talk about a biological desert.”

The short-lived annual grass is soft and green for a couple of months in the spring, when animals eat it. But for most of the year, cheatgrass is dead, resembling a parched, scraggly lawn.

In the past, lightning fires probably burned through Wyoming big sage lands in cycles ranging from several decades to more than a century. But in cheatgrass country, the flames return every five to 10 years -- killing whatever baby sage had managed to take hold since the previous blaze.

The exotic species was probably introduced to the West in the late 1800s as a contaminant in wheat seed brought by farmers from Russia and Eastern Europe.

Millions of sheep and cattle then cleared the way for the prolific invader, whose spiky seeds traveled on livestock fur and colonized areas stripped of native grasses by overgrazing. By the 1930s, cheatgrass had settled in. Periodic wet years in recent decades helped it conquer more territory.

As the sage acreage has shrunk in the Snake River raptor area, so has the black-tailed jack rabbit population, the main prey for nesting golden eagles. Their numbers are in turn dropping.

A delicate operation

Trying to reverse the ecological tide is maddeningly difficult.

Sage reseeding “is a crapshoot,” Pellant says. If there’s not enough moisture or it’s too hot, the tiny sage seeds -- the size of specks of ground pepper -- dry out and won’t germinate. Freezes can kill infant plants. Another fire will wipe them out.

Simply figuring out the best reseeding techniques has required an inventor’s ingenuity. In the 1980s, the first sage reseeding attempts were made from the back of a pickup truck. Then the “Jarbridge sagebrush seeder” was devised. It worked like a big fertilizer spreader pulled behind a truck, followed by a row of rolling tires to press the seeds into the soil.

Aerial drops have been the favored method because they can quickly cover large areas. But they often don’t work because the sage seed spreads too lightly on the ground. Federal researchers are working with engineers to modify farm seeding equipment to apply sage with other natives.

In a big fire year, the demand for seed is enormous. Much of it comes from a cavernous BLM warehouse near the Boise airport that is stacked nearly to the ceiling with pallets of bulging bags.

The building can hold 1 million pounds of seed, collected in the wild by commercial operations or cultivated. During a busy fire season, the storehouse will be filled and emptied several times over.

There are redolent sacks of antelope bitterbrush seed, Indian ricegrass, Russian wildrye, squirrel tail, bluebunch wheatgrass and arrowleaf balsamroot. A walk-in cooler that smells like a menthol factory is crammed with bags of sage seed, winterfat and forage kochia, a Eurasian native that is planted in fire-resistant green strips.

The hard-to-collect wild seed can cost as much per pound as porcini mushrooms.

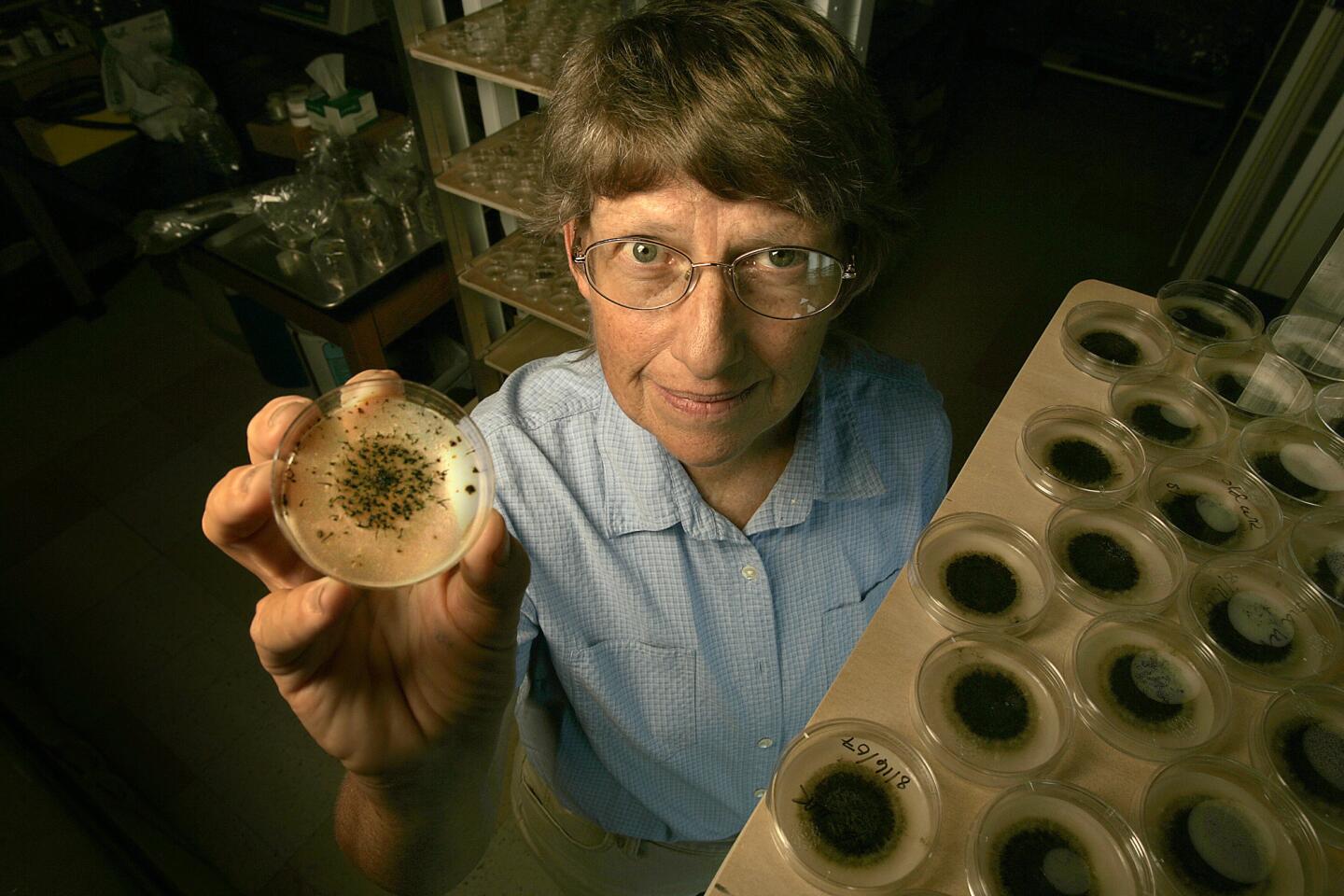

A few hundred miles away, in Provo, Utah, federal research ecologist Susan Meyer is pursuing another tack in the cheatgrass wars.

For the last decade, she has peered through microscopes into Petri dishes at the U.S. Forest Service Shrub Sciences Laboratory, searching for the perfect biological weapon.

She started her hunt after years of native plant restoration work. “I thought, ‘You’ve got to get rid of this weed or this is all an exercise in futility.’ ”

Meyer is now on her third candidate, a naturally occurring fungal disease she has nicknamed the “black fingers of death.” It attacks dormant cheatgrass seeds, injecting a toxin that disrupts cell division and stops germination.

“You know,” she says, “if I could actually do something about this, I would be the savior of the West.”

She is not very hopeful.

On a hot day last summer, the air smelled like a barbecue and the nearby Wasatch Range was wrapped in a gauzy veil of smoke from the massive Milford Flat fire to the south.

In the lab, Meyer had just made a depressing discovery. The slimy little black fingers of the fungus were growing out of the seeds of wild rye, meaning it can infect not just the hated cheatgrass but desirable plants as well.

Even if she develops the ultimate cheatgrass killer, Meyer doubts society will want to invest the hundreds of millions of dollars it would take to restore the sage country of cowboy lore. “From the Rockies to the Sierra Nevada, it’s going to be one giant weed patch.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.