Not too big to fail

Faced with the imminent collapse of Bear Stearns Cos., leaders of the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department used taxpayer guarantees to persuade JPMorgan Chase & Co. to scoop up the troubled investment bank. Similarly, with investors fleeing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the Fed, Treasury and Congress promised tax dollars to rescue the mortgage giants. Now, U.S. automobile manufacturers think it’s their turn. Outmaneuvered by leaner foreign rivals, they want Congress to provide loans at below-market rates to finance their long-overdue investments in new technologies.

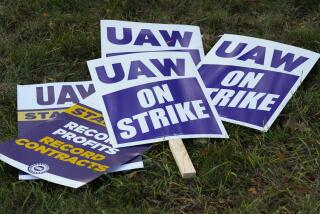

If Bear Stearns, Fannie and Freddie are important enough to merit a helping hand from Washington, why not show some taxpayer-funded love to GM, Ford and Chrysler? Aren’t the Big Three, which collectively employ nearly 250,000 people in the U.S., also “too big to fail”?

The short answer is no, they’re not. Ford Motor Co., General Motors Corp. and Chrysler may be under more stress than many other companies, with high commodities costs, skyrocketing gas prices and the slowing economy combining to raise expenses and cut revenues. But the stress is just making it harder for the Big Three to ignore the long-festering problems in their businesses. They had higher production costs than their competitors (including those that built plants in the U.S.), so they focused on bigger models with higher profit margins. As a result, they were slow to respond to the demand for vehicles with better fuel economy. When gasoline hit $4 a gallon, other manufacturers were ready with numerous well-built small cars. The Big Three, however, still had to retool U.S. truck and SUV plants to build the compacts they were already making and selling overseas.

The automakers say the government is practically obliged to provide subsidies to make up for the $100 billion in costs Congress imposed in last year’s energy bill, which required cars and trucks to go farther between fill-ups. This argument overlooks the fact that consumers are way ahead of lawmakers, as usual, in demanding change from Detroit. Nor do the high interest rates charged by private lenders justify turning taxpayers into the Big Three’s bankers. Washington can’t be expected to step in for commercial lenders whenever money gets tight.

U.S. automakers can’t blame Washington for the fix they’re in. And although it would be easier to prop up the aging manufacturers than deal with their collapse, it’s not the right strategy. The flip side of being free to succeed is being free to fail. When government intervenes, it tells businesses that they don’t have to be smart, far-sighted and nimble, they just have to be large.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.