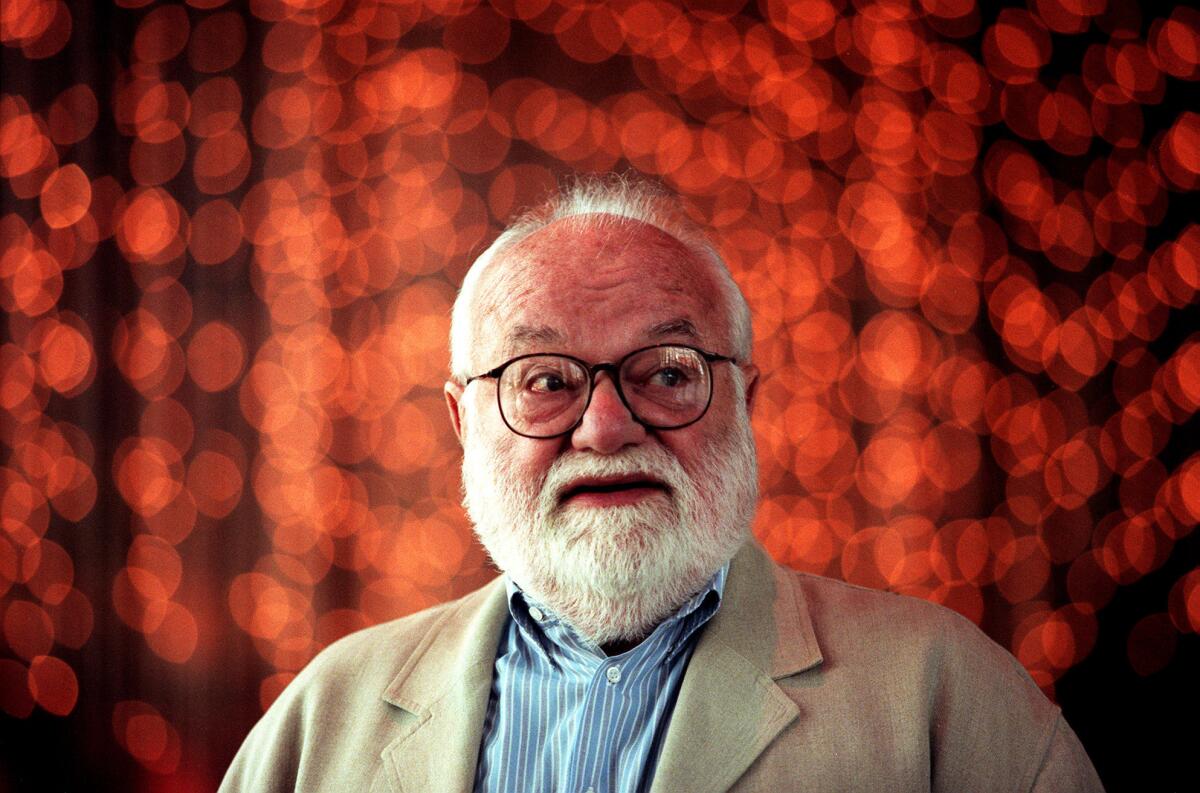

Saul Zaentz dies at 92; Oscar-winning producer of ‘Amadeus,’ ‘Cuckoo’s Nest’

It would be hard to find someone who worked with three-time Oscar-winning movie and music producer Saul Zaentz and came out of it feeling neutral about him.

Some admired him, including director Milos Forman, who won Oscars for two Zaentz films, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and “Amadeus.” “It was a wonderful collaboration,” Forman said Saturday. “Usually there is some friction between the producer and director or whatever. But with him, never.”

And then there is John Fogerty, songwriter and singer with Creedence Clearwater Revival. He is one of several people and companies who battled Zaentz in court over various matters, but the showdown with Fogerty was particularly nasty.

“The way I view Saul Zaentz and his henchmen … if I was walking down the street and those rattlesnakes were walking towards me, I would give them a wide berth,” Fogerty told the New York Times in 2005.

But there is no denying that Zaentz was a fierce, independent powerhouse who fought for the projects he loved, even when far bigger companies dismissed them as non-commercial.

“I don’t worry about what everyone wants to see,” he told the Charlotte Observer in 2003. “I make movies that please a writer, director and myself. I always think there are enough people smart as me and sensitive as me.”

Zaentz, 92, died Friday at his home in San Francisco. The cause was complications of Alzheimer’s disease, said his nephew, Paul Zaentz.

He was a credited producer on nine films, beginning in 1975, after a successful run in the music business. Three of those films, including the first, “Cuckoo’s Nest,” won best picture Academy Awards.

He had flops, too, but as a hands-on producer, he took the blame. “You always think you got it, you’re going to make a good picture,” Zaentz told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2007. And when it fails, “You really feel terrible. You want to know what you did wrong. You want to know how you could’ve made a better picture and why you didn’t make a better picture.”

The reason he got to make literary, non-mainstream films in the first place, besides an abundance of chutzpah, was that he was willing to put his own resources on the line.

“He was not afraid to use his own money,” Forman said. “If he used his own resources to develop a project, that made it his own.”

Saul Zaentz was born Feb. 28, 1921, in Passaic, New Jersey, to Eastern European Jewish parents. As widely reported, he took to gambling at an early age. But Paul Zaentz, who also grew up in Passaic, said his uncle was not a high roller, at least not back then. “No one had that kind of money,” he said.

Saul Zaentz enlisted in the Army during World War II, according to the Chronicle, and then studied animal husbandry at Rutgers University on the G.I. Bill, with an eye toward becoming a chicken farmer.

“It was a way to make a living,” he told the newspaper. “I’d be my own boss.”

Working for a bit on an actual chicken farm changed his mind about that, especially because of the long hours. He headed for San Francisco, where he pursued a career in the music business. After working for noted jazz producer Norman Granz, he began working at Fantasy Records, a small label which had recorded several jazz greats. Zaentz moved up the ranks to produce records and run various departments, and in 1967 he and investors bought the label.

The most successful band to come out of Fantasy was Creedence Clearwater Revival, fronted by Fogerty. But the relationship between Zaentz and Fogerty eventually became so toxic — over rights, fees and other matters — that it also pitted band members against each other, and lawsuits flew back and forth.

At one point, Zaentz filed a defamation lawsuit against Fogerty over the song “Zanz Kant Danz,” which some believed depicted the producer as dishonest and greedy. The parties eventually settled out of court, and Fogerty changed the title of the single to “Vanz Kant Danz.”

On Friday night, Fogerty posted a link to the song on his Facebook page. A spokesman for the musician said Fogerty had no comment on Zaentz’s death.

With the success he achieved in music, Zaentz turned to the movie business. Veteran actor Kirk Douglas had been trying to get the Ken Kesey novel “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” made into a film for years, with no luck. Zaentz also loved the book — he and the actor’s son, Michael, co-produced, hiring the Czechoslovakian director Forman, who had few credits in the U.S.

The film, released in 1975, took five Academy Awards, including for the producers, director and star Jack Nicholson, who played Randle P. McMurphy, a social misfit who causes trouble at a mental institution.

“Amadeus,” with Forman again directing, gave him another personal hit in 1984. Based on the hit Peter Shaffer play, it depicted the rivalry between composers Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Antonio Salieri.

Zaentz first saw the play in New York and felt that some major changes were needed for the film, not the least of which was much more music by Mozart.

“I said to [Forman] that the movie had to focus more on Mozart and his music and less on the jealous rival, Salieri,” Zaentz told the Chicago Tribune in 1988. “I think the play had about 10 minutes of music; the movie had about two hours.”

“Amadeus” won eight Oscars.

“The English Patient,” based on the Michael Ondaatje novel, brought home nine Oscars in 1997. Zaentz was vocal about having had to battle various studio executives who wanted to cast the movie with big American stars. Eventually, he found backing with Miramax, which gave him the creative freedom to cast Ralph Fiennes, Kristin Scott Thomas and Juliette Binoche.

Zaentz told The Times that he put $5.5 million of his own money into the $33-million picture, and that he and several actors deferred their salaries. The movie was one of his biggest hits, grossing $232 million worldwide.

At the Oscars ceremony, Zaentz not only won the best picture award but also the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award in recognition of his accomplishments.

With success in the movie business came more lawsuits. He sued Miramax and its former owner Disney over $20 million in profits for “The English Patient.”

The producer was also embroiled in an $80-million merchandising lawsuit involving the estate of J.R.R. Tolkien, the author’s publisher and Warner Bros.

Both lawsuits are still pending, according to Paul Zaentz.

One of Zaentz’s passion projects was bringing to the screen Peter Matthiessen’s novel “At Play in the Fields of the Lord.” Zaentz pursued the rights and ultimately got to make the movie with director Hector Babenco.

Filming in the Brazilian rain forests was often dangerous. “We have taken every precaution we can think of here, but this is a very exotic place. There are things we can’t control. There are funguses in the air that you can breathe in,” Zaentz told The Times in 1990.

When the three-hour movie was released the following year, it received mixed reviews and flopped at the box office.

His last movie was 2006’s “Goya’s Ghosts,” a historical drama directed by Forman that was pummeled by critics and fared poorly at the box office.

Zaentz said the movie industry changed during his time in the business, making it tougher for relatively small films to be made. “It’s all about money,” he said in the 2007 Chronicle interview. “You look at guys who made pictures, the older guys, you could see they read their books.”

He took obvious pride in his Oscars, saying he had read of a study that claimed people who win the awards live four years longer. “I have three,” he said. “I don’t want them to run concurrently. Can I pile them on top of each other?

“Let’s see, the 12 years were up yesterday.”

Zaentz was twice divorced. He is survived by four children — Athena, Dorian, Jonnie and Josh — and seven grandchildren.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.