Conditions could give Seahawks a leg up in Super Bowl

The East Rutherford Seahawks?

It’s got a weird ring to it, but there’s a chance that Mother Nature will give the Seahawks a slight home-field kicking advantage in the Super Bowl on Feb. 2 at MetLife Stadium.

The cities of East Rutherford, N.J., and Seattle are both approximately at sea level, while the Denver Broncos’ Sports Authority Field rises a mile into the sky, where atmospheric pressure is a lot lower and the air is generally less dense.

Broncos kicker Matt Prater is accustomed to kicking in Denver’s rarefied air.

“In Denver, on average, there are fewer molecules per cubic foot in the air,” says Tim Gay, a physicist (and author of the book “The Physics of Football”) at the University of Nebraska, while at sea level “there are more molecules for the ball to bump into, and it doesn’t go as far,” he says. The same principle of physics explains the barrage of home runs hit at Coors Field pre-humidor.

“I know Prater’s a tremendous kicker, but he isn’t going to be kicking any 64-yarders in New York,” says former kicker Paul McFadden, referring to Prater’s record-setting 64-yard boot this season. And McFadden knows the challenge firsthand, having kicked in plenty of harsh conditions during his time with the Philadelphia Eagles and New York Giants in the 1980s.

Even without considering things such as air pressure and density, a field-goal kick requires the perfect confluence of kinesiology and physics, says Gay.

Gay, who was an offensive lineman at Caltech in the 1970s, says the two most important factors in a field goal are the mass and length of the kicker’s foot and leg, which together act as a large pendulum, and the speed with which the side of the foot hits the ball.

Although a tall, muscular kicker may have something of an advantage, it’s not all about strength. That intangible called athleticism provides the technique necessary to whip the leg and foot around in an arc that maximizes foot speed. On a kickoff, a pro’s foot moves about 60 mph, says Gay, transferring enough energy to launch the ball at 100 mph.

Planting your other foot at the right angle and in the right place and where the side of your foot strikes the ball are also critical, adds McFadden, who kicked barefoot (“it didn’t hurt,” he claims).

“The bottom third is the sweet spot of the football,” he says.

Hitting the sweet spot might not matter much, however, if the ball isn’t perfectly upright.

Andre Mazzoleni, an engineer at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, recently co-authored a report in the journal Sports Engineering demonstrating the importance of the hold on a field goal. A ball held at an angle of just 20 degrees can lead it to drift 3.5 feet, according to Mazzoleni’s mathematical model, a critical amount when the goal posts are only 18.5 feet apart.

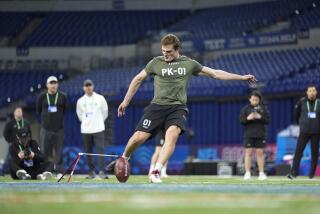

Even if the Broncos’ Prater and Seahawks kicker Steven Hauschka (and their holders) get all their fundamentals down, there’s still a lot that can go awry in the swirling Meadowlands. Although it’s still too early to tell whether snow or sleet is in the cards, there’s a good chance it will be cold.

In cold weather, the air is denser, which keeps the ball from going as far, says Gay. In addition, if the ball itself gets cold, it gets rigid, meaning more energy is spent deforming the ball when the foot strikes it.

“A cold ball doesn’t compress, so it doesn’t travel as far,” explains McFadden, who says he left New York for Atlanta after the 1988 season to get out of the north and its cold conditions.

And we haven’t even mentioned wind, which creates drag on the ball, and which McFadden calls “treacherous” at MetLife.

Perhaps the Broncos’ offense or the Seahawks’ defense will be so dominant that Prater and Hauschka will remain swaddled on the sidelines, tangential to the game’s outcome.

But if it comes down to kicks, a lot has to go right to split the uprights.