NASA’s next Mars rover will look for signs of life on an ancient crater lake

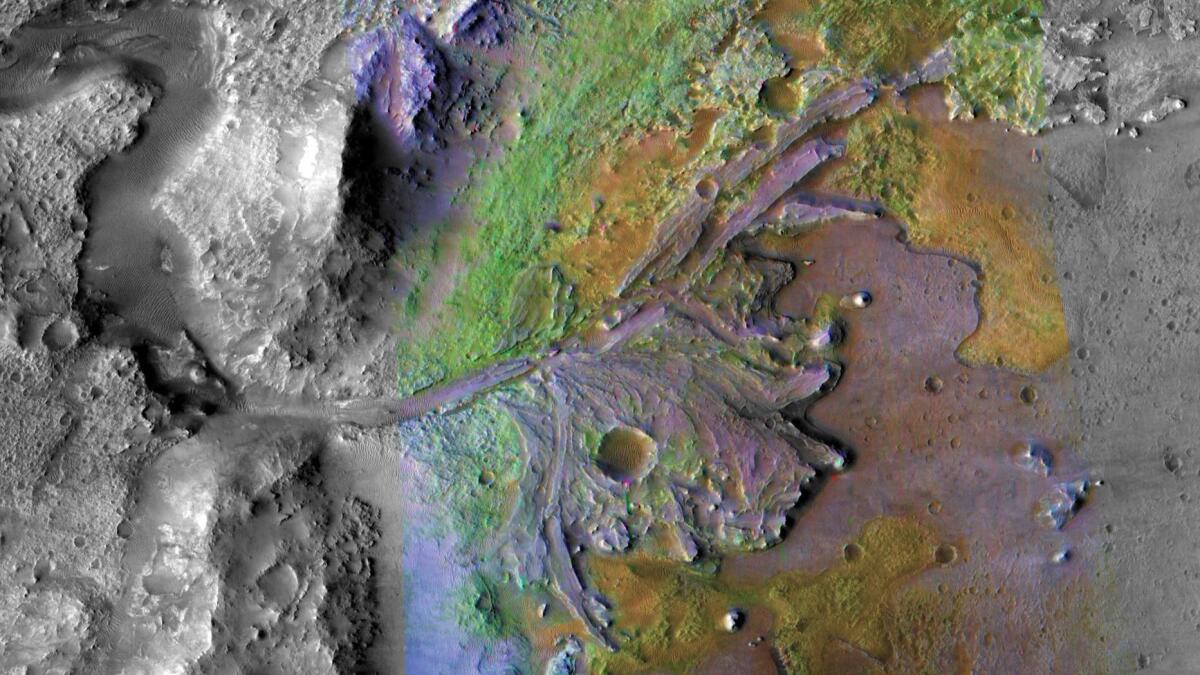

In a search for ancient life on Mars, NASA will send its next rover to explore Jezero Crater — the site of a former delta and lake.

The rover, which is scheduled to launch in 2020, is equipped with a drilling system that can collect and store rock samples that contain clues to Mars’ ancient past. Once the samples are cached, NASA hopes to send follow-up missions to retrieve the samples and return them to Earth.

“Getting samples from this lake-delta system will revolutionize how we think about Mars and its ability to harbor life,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator for science.

The landing site selection came after years of research and days of fierce debate over the best spot to look for evidence of ancient life on an alien world. Among the alternatives being considered were Columbia Hills, an ancient hot spring that was explored by the now-defunct rover Spirit, and Northeast Syrtis, a network of ancient mesas that may have harbored underground water.

Ultimately, Zurbuchen said, Jezero was selected for the diversity of its terrain. Each type of rock at the site — from clays that could preserve signs of ancient organisms to volcanic rocks that hint at Mars’ planetary evolution — should help the rover achieve its two main science goals. First, to determine what the Red Planet’s environment was like deep in the past, and second, to figure out if life ever got going there.

Results from past missions have revealed that Mars was not always the desolate desert world we see today. Dormant volcanoes suggest it once boasted intense volcanic activity. And landforms like the dried-up delta at Jezero Crater demonstrate that liquid water existed on the surface — which means Mars may have had a thicker atmosphere to keep water from boiling away.

This new view of Mars resembles what is known about early Earth. And scientists know microbial life began here as early as 4 billion years ago.

If it happened here, why not there?

Jezero Crater is the best place on Mars to probe that question, said Tim Goudge, a geologist at the University of Texas who is one of the leading advocates for the site. Deltas are beloved by scientists because of the way they gather sediments from across a watershed and deposit them in layers, which eventually harden into rock. Many of the most ancient fossils found on Earth come from this kind of environment.

If a microbe ever swam in Mars’ waterways, its organic remains may still be buried in the mudstones along the rim of Jezero Crater.

“Sedimentary rocks tell us the history of what’s been happening at a site,” Goudge said. “It’s recorded in the layers, and you can read them like a book.”

In a memo announcing his selection, Zurbuchen noted that Jezero offered opportunities for exploration after its initial mission, which will last 1.5 Martian years (or about 2.8 Earth years). The crater is not far from an area known as Midway, which shares many characteristics with Northeast Syrtis. At a recent workshop to assess the potential landing sites, members of the project science team for Mars 2020 said that an extended mission connecting Jezero to Midway might allow scientists to explore the best of both sites.

Jezero Crater is a more treacherous environment than the kinds NASA usually lands in. Often, landers have to arrive at what scientists jokingly refer to as a “parking lot” — a flat, featureless region — and then drive long distances to reach rocks of actual interest. But an innovative new technology called terrain relative navigation (TRN), which allows the spacecraft to compare images of the landscape beneath it to a map of known hazards, should make it possible for the rover to land safely.

Since TRN has never been deployed before, Zurbuchen asked engineers for an additional analysis of the technology. Without assurance that the technology will work as designed, the complex environment at Jezero might pose too high a risk for landing. But Zurbuchen said he was happy with the progress on TRN so far.

Kaplan writes for the Washington Post.