Modified Pap tests can show early warning signs of other gynecological cancers

The Pap test has already reduced the incidence of cervical cancer by more than 60%. Now it may become a key step in the early detection of two other gynecological malignancies — ovarian and endometrial cancers — that have been notorious killers because they’re typically caught so late.

A new study has found that by genetically analyzing the harvest of cells from a Pap smear, doctors could identify 81% of endometrial cancers and 33% of ovarian cancers. Some of those cancers were in their earliest stages, when they’re more likely to respond to treatment.

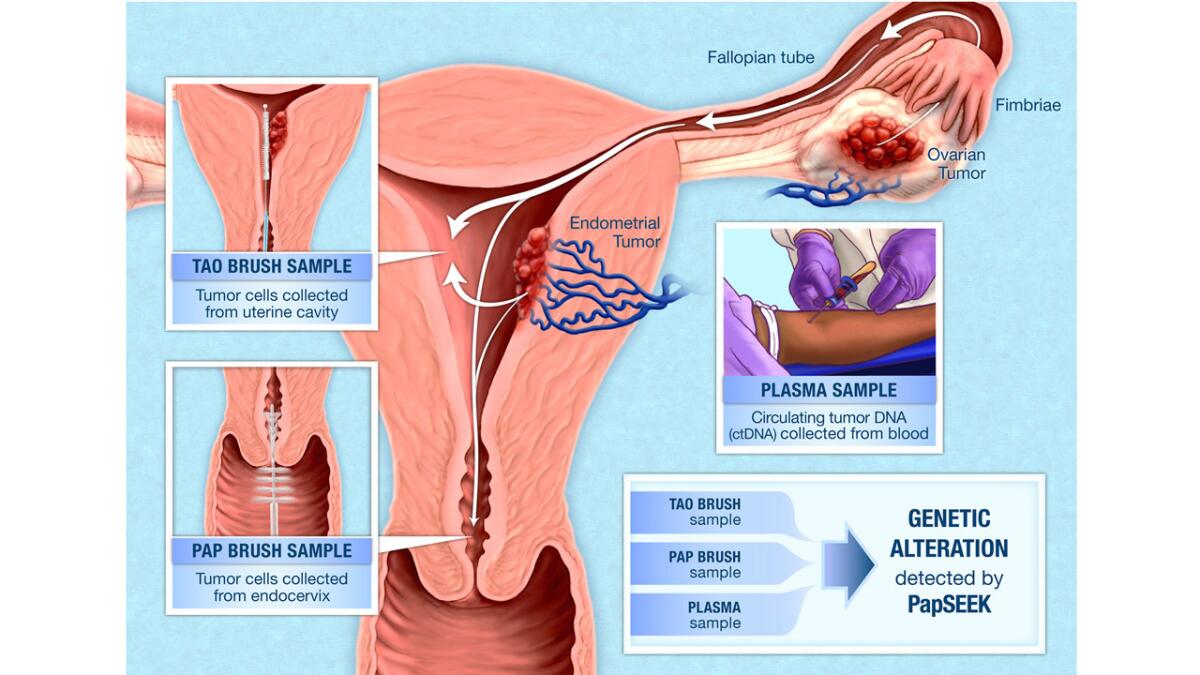

When the Johns Hopkins University researchers tested an alternative means of collecting cells — a longer brush that sweeps cells from the lining of the uterus — they positively identified endometrial cancer in 93% of cases and ovarian cancer in 45% of cases.

And when they added a blood test to the ovarian cancer screening regimen, they were able to detect that deadly cancer in 63% of patients who had it.

“Having the possibility to detect these cancers earlier is very exciting,” said Dr. Nickolas Papadopoulos, a coauthor of the study, which was published Wednesday in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

It’s the latest example of how scientists hope to detect cancer earlier and with greater precision by looking in blood and other easily accessible fluids for cells that bear the telltale genetic mutations of cancer.

While such “liquid biopsies” have not yet made their way into widespread use, they hold the promise of revolutionizing cancer screening.

In January, the same research team presented promising findings in the journal Science on a blood test called CancerSEEK that’s capable of detecting malignancies of the liver, stomach, pancreas, esophagus, colon, lung and breast. Earlier this week, they published findings in the journal eLife on a urine test to detect cancers of the urothelial tract or urinary bladder.

As a screening test for cervical cancer, the Pap smear has been a staple of gynecological checkups for more than six decades. It’s named for Dr. George Papanicolaou, the physician who first showed that cancerous cells of the cervix could be detected by microscopic inspection.

The Pap test has dramatically driven down deaths from cervical cancer, which used to be one of the most common cancers in women. However, the test does a poor job of detecting endometrial or ovarian cancer, which together kills about 25,000 women in the United States each year.

Women thought to be at high risk of those cancers are sometimes screened with a blood test that detects an immune system biomarker called CA-125, or with a transvaginal ultrasound that looks for telltale thickening of the uterus’ endometrial wall. But those tests fail to detect many cancers, and also send up a lot of false alarms. So they’re frequently not used until a woman complains of symptoms.

The result is often a diagnosis at an advanced stage, when treatments are more invasive and less likely to be successful.

In the new study, the researchers measured the accuracy of their PapSeek test on 1,658 women. They already knew that 1,002 of the women were free of either cancer and 656 of them had either ovarian or endometrial cancer.

Researchers collected cervical fluid samples with a Pap smear brush and a slightly longer tool called a Tao brush, which reaches beyond the cervix and into the uterus, nearer to where ovarian and endometrial cancers take hold. Then they used the PapSeek test to sequence the samples, focusing on 18 genes that tend to develop mutations in those cancers. The test also checked the samples for aneuploidy, the presence of abnormal numbers of chromosomes in cells.

When the researchers used the longer Tao brush, they were able to detect endometrial cancer in all but 7% of the women who had the disease, and close to half of the ovarian cancers. Combined with the fact that these tests were performed with a mere swipe of the uterine wall, these measures of “sensitivity” — the ability to detect cancers that are actually there — represent a major improvement over the screening tests currently available.

When they supplemented the analysis of Pap and Tao brush samples with a hunt for mutated cells in the women’s blood, they were able to detect ovarian cancer in well over half of those who had it.

When endometrial and ovarian cancers are especially aggressive and when they have progressed to advanced stages, they are easier to find with existing screening methods. But an important measure of a test’s usefulness is whether it can detect the most aggressive types of cancer before they have metastasized.

By that measure too, the PapSeek test looked promising. When it was used to scan the Tao brush samples, it identified 89% of the high-grade endometrial cancers in patients while their malignancy was still confined to the endometrium. It was also able to identify 80% of those with high-grade ovarian cancers before they had spread.

Just as important, the tests were remarkably good at avoiding false-positive signals, which would needlessly alarm women and lead to riskier and more-invasive tests to confirm a diagnosis. For both types of cancer, the PapSeek test’s “specificity” — its ability to accurately recognize the absence of disease — approached 100%.

Papadopoulos said he was surprised and heartened that the Pap test — or a close variant of it — could be repurposed to look for gynecological cancers that are typically caught way too late.

While the team hopes to improve the test’s sensitivity, he said that even this early version would likely boost women’s chances of earlier detection by a considerable margin.

“It doesn’t have to be perfect to help at least some women” who might otherwise die of these stealthy cancers, Papadopoulos said. “Women are already used to having Pap smears, and everyone can give a vial of blood.”

MORE IN SCIENCE

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch counts 1.8 trillion pieces of trash, mostly plastic

To avoid germs on an airplane, consider booking a window seat

The National Academies take a hard look at the safety and quality of abortion care in the U.S.