In the heart of Pluto, some of the youngest terrain in the solar system

When NASA’s New Horizons Spacecraft beamed back the first close-up images of Pluto’s surface in July of 2015, scientists were flabbergasted.

In those early, dizzying days last summer, the cold, distant dwarf planet was revealed to be a diverse and geologically active world with wide flat plains, towering mountains, rounded hills and a hazy atmosphere.

See the most-read stories in Science this hour >>

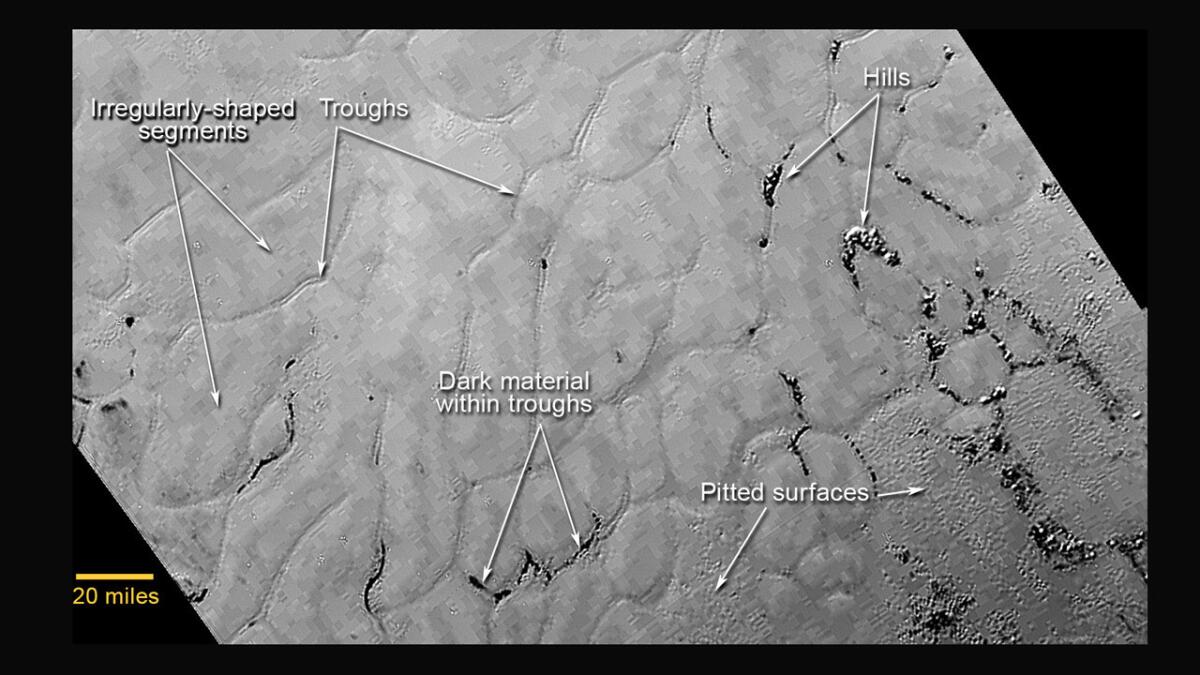

Almost all of it was unexpected, but one area in particular had researchers stumped. It was a bright sheet of nitrogen ice containing a series of smooth polygon shapes each between six and 24 miles in diameter and separated from one another by what appeared to be shallow troughs.

What was particularly striking about the region is that the whole 650 by 500 mile area was craterless, suggesting it had to be extremely young, geologically speaking.

“It couldn’t possibly be more than 100 million years old, and is possibly still being shaped to this day,” said Jeff Moore, leader of the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging team at NASA’s Ames Research Center at the time. “It could be only a week old, for all we know.”

He told reporters that he had nicknamed it “not-easy-to-explain-terrain.”

Geology on ice: Scientists unveil video of frozen mountains and plains on Pluto

Now, almost one year later, a pair of papers have appeared in Nature that seek to describe the processes that have sculpted this strange region.

The authors agree that the frequent resurfacing of Sputnik Planum is probably due to a process called convection.

To understand how this works, you first need to know that nitrogen ice is softer and more viscous than water ice – even at Pluto’s surface temperature of 35 degrees above absolute zero.

Scientists say that heat generated by the decay of radioactive materials in the interior of the planet warms the bottom of the thick sheets of nitrogen ice found in Sputnik Planum. The heated material expands thermally and becomes less dense. This makes it buoyant enough to rise up through the viscous ice layer, only to be cooled at Pluto’s surface and sink back down.

You can think of the process as a giant lava lamp that turns over the surface of the dwarf planet every 500,000 to 1 million years. That may sound like a long time, but experts say that makes Sputnik Planum one of the youngest terrains in the solar system.

“Geologically, it is just whipping around,” said Andrew Dombard, a planetary scientist at the University of Illinois at Chicago who was not involved in either study. “It is stunning. You don’t expect this kind of activity from a body that is so small and so far from the sun.”

The two papers agree that the convection process is responsible for Sputnik Planum’s polygons, but they are are not in perfect agreement.

One of the studies, lead by Alexander Trowbridge of the Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., found that the individual cells of warm ntirogen that have bubbled up to Pluto’s surface are about as deep as they are wide. The other study, lead by William McKinnon of Washington University in St. Louis, Mo., report that the cells are less tall then they are wide.

And this, says Dombard, is where things get interesting.

Scientific calculations suggest that Sputnik Planum is home to all the nitrogen on Pluto – a finding that scientists can’t yet explain.

If the Trowbridge group is right, and the cells are as deep as they are wide, that means Sputnik Planum – and Pluto itself – has more nitrogen in it then if McKinnon’s group is right.

Both hypotheses will be discussed by the scientific community and tested and retested until a favorite emerges.

Dumbard said that once scientists come to agreement on how much nitrogen there likely is on Pluto, they will be in a better position to investigate the even more puzzling question of why all of it ended up in one place.

“That is the part that is going to have the scientific community scratching their head for a while,” he said.

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE FROM SCIENCE

Pluto is defying scientists’ expectations in so many ways

Why male fruit flies have such enormous sperm

Health experts question federal study linking cellphones to brain tumors