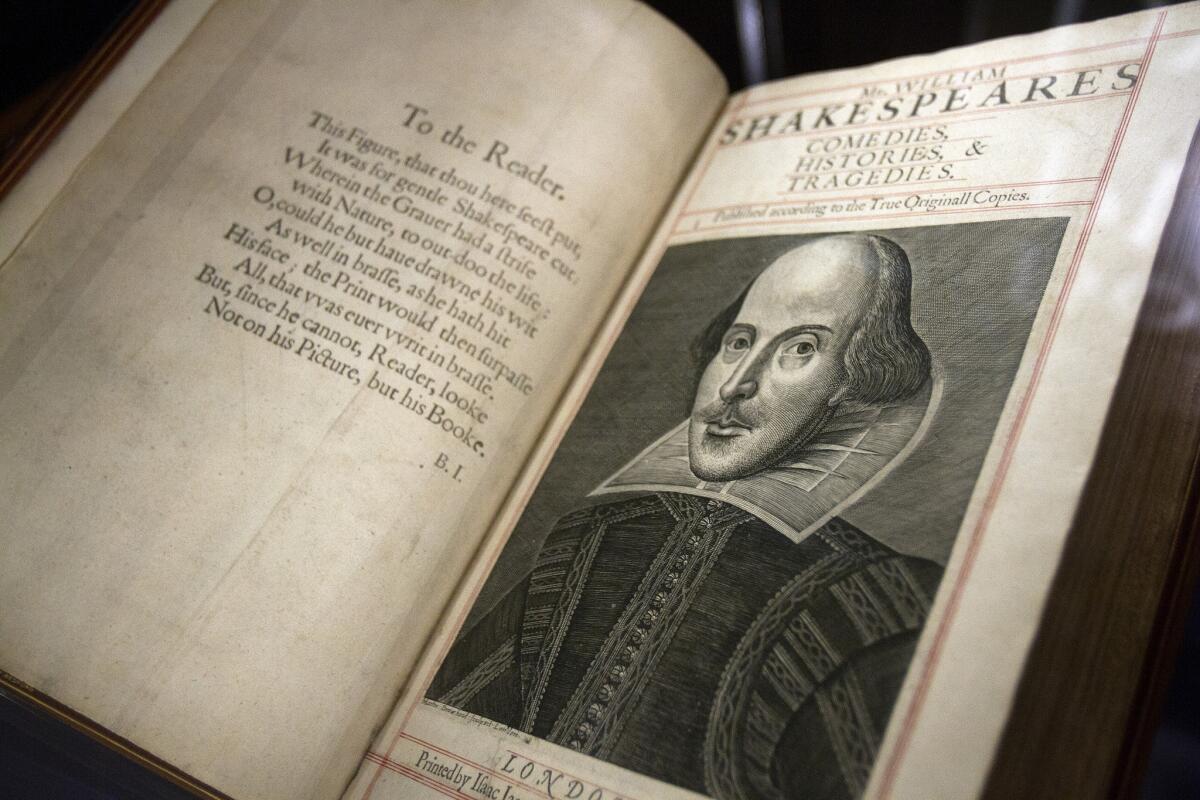

Study finds a disputed Shakespeare play bears the master’s mark

Chalk up another one for The Bard.

“Double Falsehood,” a play said to have been written by William Shakespeare but whose authorship has been disputed for close to three centuries, is almost certainly the work of the 16th century poet and playwright, new research finds.

Shakespeare appears to have had some assistance in the project from John Fletcher, a contemporary who is thought to have co-written three plays with the Bard -- including one on a theme similar to that of “Double Falsehood” -- near the end of Shakespeare’s life.

Nevertheless, “the entire play was consistently linked to Shakespeare with a high probability,” the authors of the new study wrote.

Those findings came after two researchers subjected the play’s language to psychological scrutiny and computer analysis so exhaustive that not a single pun, put-down, preposition or “prithee” went uncounted. The researchers’ method supercharges the practice of “styleometry” long used by scholars of literature by recruiting computers to churn through millions of sentences of text.

Aided by machine-learning programs, computers quickly discern linguistic regularities that become an author’s “signature.” When the authorship of a book or play is contested, computer-enhanced stylometry can compare suspected authors’ “signatures” to that of the disputed work, yielding a scientific basis for assigning authorship.

In the end, two psychology professors from the University of Texas in Austin declared that the author of “Double Falsehood” -- a tale of fathers, sons, duty and love set in Andalusia -- was Shakespeare, and not his acolyte Lewis Theobold.

Theobold, a Shakespeare scholar and avid collector of manuscripts, published the play in 1728, claiming it came from three original manuscripts written by the Bard. Those manuscripts, however, were said to have burned in a library fire. In the absence of physical proof, scholars’ suspicions fell upon Theobold as a literary imposter.

Under the supervision of University of Texas psychology professors Ryan L. Boyd and James W. Pennebaker, machines churned through 54 plays -- 33 by Shakespeare, nine by Fletcher and 12 by Theobold -- and tirelessly computed each play’s average sentence-length, quantified the complexity and psychological valence of its language, and sussed out the frequent use of unusual words.

“Our results offer consistent evidence against the notion that Double Falsehood is Theobold’s whole-cloth forgery,” wrote Boyd and Pennebaker. While Theobold’s “psychological signature” was not evident, it did make “passing statistical appearances” -- probably the result of Theobold’s penchant for heavy editing, they added.

The notion -- and method -- of creating a writer’s psychological signature opens up new avenues to authenticating disputed works, wrote Boyd and Pennebaker. But they underscored that it can also be used to provide a “better understanding of individuals’ composite mental lives.”

The researchers cite longstanding research that shows that the way writers use language, the words they choose, and even the length of their sentences bespeaks their cognitive style and temperament. A deep analysis of a writer’s verbal output can “paint a very rich picture of who that person is, how he or she think, and what he or she thinks about,” they write.

For Shakespeare, much of whose life remains a mystery, the analysis offers a bit of insight: his frequent use of prepositions suggests he was rigorously educated in grammar. His heavy use of “social content words” (vs. words related to thought processes or emotion) suggests he was more attuned to social niceties and advancement than he was either cerebral or preoccupied by his own or others’ feelings, the authors write.

Follow me on Twitter @LATMelissaHealy and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.