Coronavirus outbreak is now an international ‘public health emergency,’ WHO declares

The World Health Organization declared Thursday that the deadly outbreak fueled by a new coronavirus from China has become a global health emergency, citing fears that the microbe will soon reach smaller, poorer countries incapable of stemming its spread.

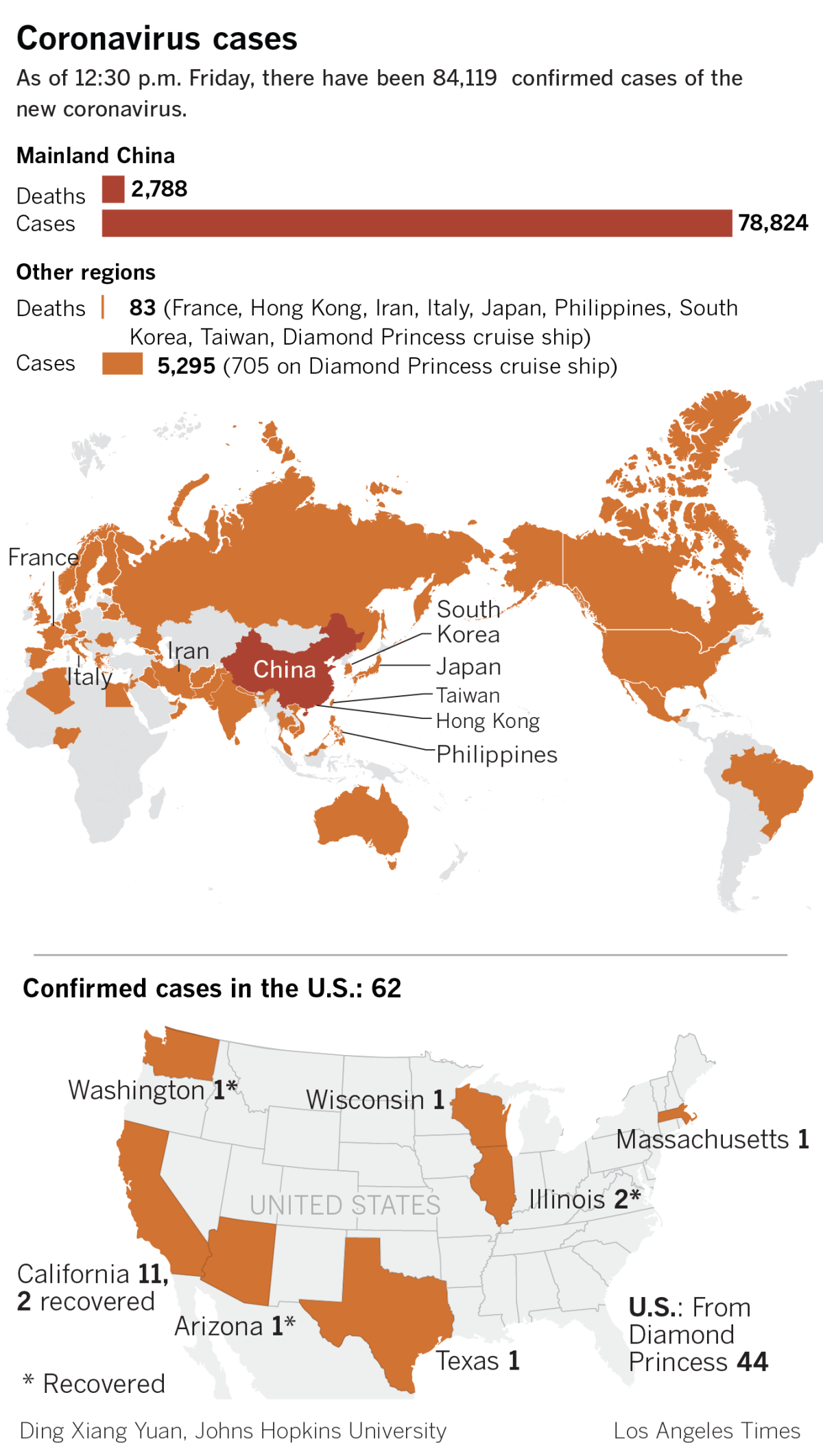

The decision will probably make new resources available to health officials around the world who are battling a virus that has sickened more than 9,770 people on four continents and claimed at least 213 lives. It will also establish WHO’s authority to lead the international response and strengthen the organization’s hand in shaping the domestic decisions of its 194 member nations.

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said the organization is not recommending any measures that would limit travel or international trade. Those are some of the most potent tools at his agency’s disposal, but they are not necessary at this time, he told reporters in Geneva.

The U.S. advised against all travel to China on Friday after the World Health Organization declared the outbreak of a new virus that has spread to more than a dozen countries a global emergency. The number of cases spiked more than tenfold in a week, including the highest death toll in a 24-hour period reported Friday.

Health experts who have been tracking the virus’ spread said the WHO’s declaration was more than justified.

“Declaring an emergency gives WHO the authority to make recommendations that are very influential,” said Lawrence Gostin, an expert on public health law at Georgetown University. “It signals to the world this is a global crisis and we all need to come together to address it.”

But experts also acknowledged that WHO has no way to enforce its recommendations or to constrain the actions of members. Even with the new declaration, the agency will be able to do little more than cajole and exhort the international community to cooperate, and to guide the efforts of philanthropies active in public health efforts.

Tedros took pains to reassure China that WHO’s declaration implied no criticism of the country’s actions, including the “extraordinary measures” it has taken to limit the spread of the novel coronavirus, known officially as 2019-nCoV. Among other things, the government ordered an unprecedented quarantine affecting 50 million people in 17 cities.

“China is setting a new standard for outbreak response, and it’s not an exaggeration,” he said.

Yet with the virus now present in 22 countries and territories, and with person-to-person transmission confirmed to have taken place in five countries besides China, the potential for it to cause mayhem in countries “with weaker public health systems” was Tedros’ chief concern.

“We must all act together now to limit further spread,” he said.

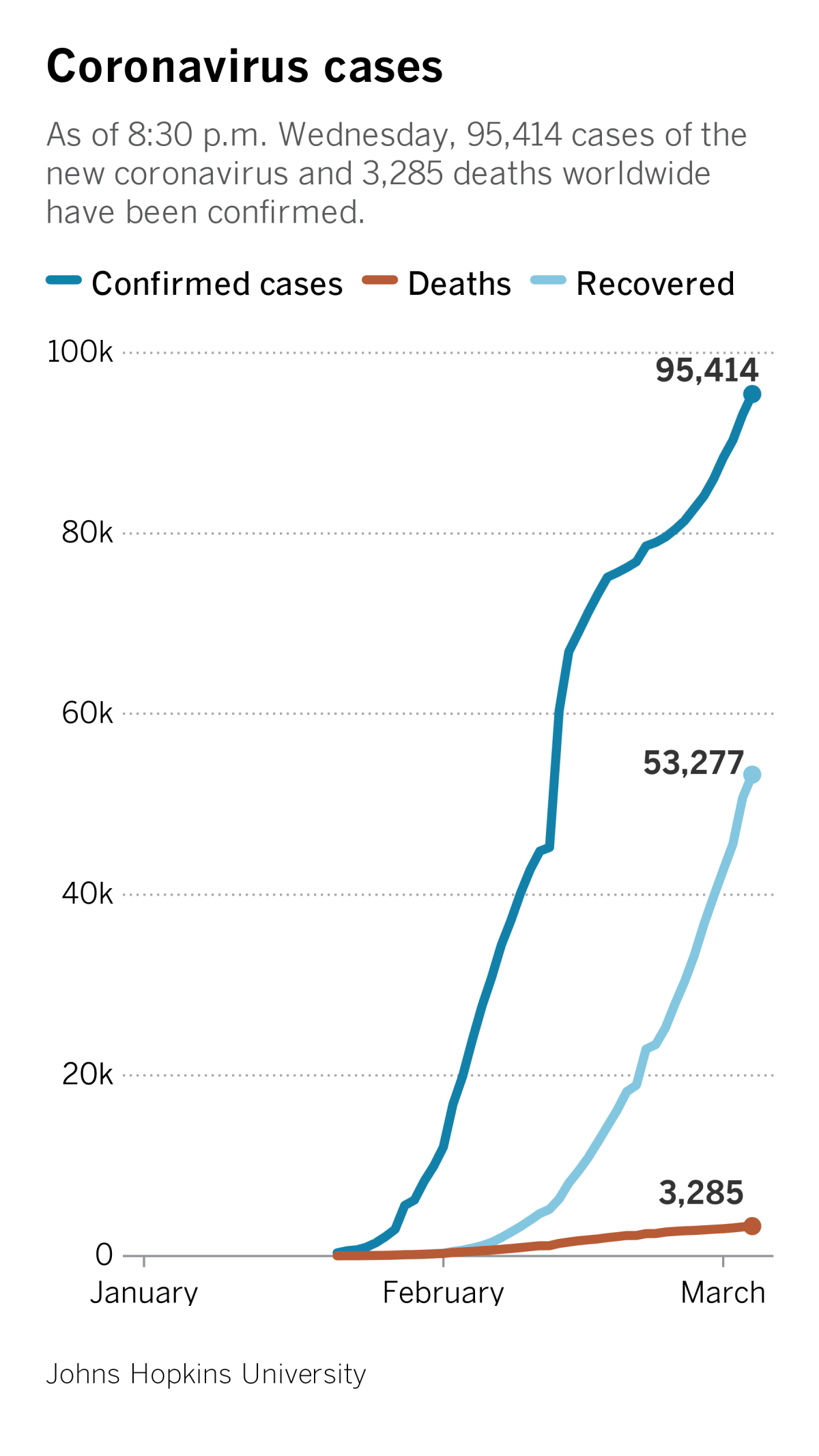

Researchers from China’s leading public health agency calculated that the epidemic established itself by doubling in size every 7.4 days, according to a report published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine. They also estimated that each person infected with the coronavirus passed it along to 2.2 others — on par with the 1918 Spanish flu.

An expert advisory committee debated for almost eight hours before recommending that WHO formally declare the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern. In doing so, the members recognized that the never-before-seen virus is spreading internationally, poses serious health threats, and could affect travel and trade.

China first informed WHO about cases of the new virus in late December. Experts say there is significant evidence the virus is being transmitted among people in China and have noted with concern several instances in other countries — including Japan, Germany, Canada, Vietnam, South Korea, France and most recently the U.S. — where there have also been isolated cases of human-to-human spread.

The spread of 2019-nCoV in Vietnam, a country with a rudimentary system in place to detect, track and isolate new infections, is particularly alarming to infectious disease experts.

Tedros made clear that the declaration must galvanize the international community’s efforts to help vulnerable countries fight the spread of coronavirus.

“We must support countries with weaker health systems” by providing them with tests that can quickly identify and treat those infected, he said. And when a vaccine to prevent infection becomes available, those countries must gain access to them, he added.

Dr. Tom Frieden, former director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, praised WHO for being realistic about the threat the outbreak presents. Thursday’s action “matches the situation on the ground,” he said.

The decision is likely to help channel more money and manpower toward countries such as Cambodia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Nepal and Thailand, all of which have seen a small number of infections. Additional resources from non-governmental organizations including Doctors Without Borders and charitable groups such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation could be extremely useful for governments struggling to bring in medical teams and identify infected persons, Gostin said.

But WHO’s direct influence is limited. It can’t force member countries to adopt trade or travel restrictions, nor can it prevent them from taking overly aggressive steps limiting the movement of people or goods.

“One sad truth about declaring an emergency is that it doesn’t legally and technically grant WHO any enhanced powers or release any emergency funding,” said Gostin, who added that such a crucial deficiency should be fixed.

In its deliberations leading to Thursday’s declaration, the WHO advisory committee relied on regulations adopted by the United Nations after the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, which sickened more than 8,000 people and caused 774 deaths. To declare an “emergency of international concern,” the agency must find that an outbreak “constitutes a public health risk to other states through the international spread of disease,” or that it poses a “significant risk of international travel or trade restrictions.”

A burgeoning Ebola epidemic in West Africa was designated a public health emergency of international concern in 2014, after the virus spread beyond its epicenter of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia to seven other countries, including the United States.

There are many things scientists really wish they knew about the coronavirus that has sickened thousands of people and caused at least 132 deaths.

In 2016, the international agency did the same for the rapidly spreading Zika virus as the mosquito-borne pathogen marched across the Americas, causing miscarriages and birth defects when pregnant women were infected.

Most recently, WHO declared a public health emergency in July as cases of Ebola mushroomed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and spilled over into neighboring Uganda.

But the agency declined on multiple occasions to give that status to an outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome, which is caused by another coronavirus that jumped from camels to humans. Though it sickened nearly 2,500 people in 27 countries and caused 858 deaths, WHO said travel and trade restrictions would not serve a public health purpose.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.