U.S.-based trio share chemistry Nobel for quantum dots, used in electronics and medical imaging

STOCKHOLM — Three U.S.-based scientists won the Nobel Prize in chemistry Wednesday for their work on quantum dots — particles just a few atoms in diameter that can release very bright colored light and whose applications in everyday life include electronics and medical imaging.

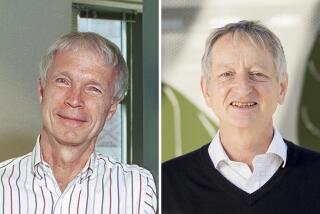

Moungi Bawendi of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Louis Brus of Columbia University and Alexei Ekimov of Nanocrystals Technology Inc. were honored for their work with the nanoparticles, which “have unique properties and now spread their light from television screens and LED lamps,” according to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which announced the award in Stockholm.

Quantum dots’ electrons have constrained movement, and this affects how they absorb and release visible light, allowing for very bright colors.

“Why does it matter ... that we can make tiny particles that nobody can see, but they have colors?” asked Pernilla Witting-Stafshede, a member of the Nobel committee that awarded the prize. “This is actually used today both in medicine and technology already out today. ... But we have displays on TVs, in your cellphone, that use quantum dots inside to make just brighter colors.”

The dots are nanoparticles that glow blue, red or green when illuminated or exposed to light. The color they emit depends on the size of the particles. Larger dots shine red, and smaller dots shine blue. The color change is due to how electrons act in more or less confined spaces.

Though physicists had predicted these color-change properties as early as the 1930s, creating quantum dots of specific controlled sizes was not possible in the lab for five decades more.

The Nobel Prize in physics goes to three scientists, including one at Ohio State, for giving us a glimpse of electrons in an attosecond -- one-billionth of one-billionth of a second.

“For a long time, nobody thought you could ever actually make such particles, but this year’s laureates succeeded,” said Johan Aqvist, chairman of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, adding that, for the particles to be useful, makers have to exercise “exquisite control of their size and surface.”

Ekimov, 78, and Brus, 80, were early pioneers of the technology, while Bawendi, 62, is credited with revolutionizing the production of quantum dots “resulting in almost perfect particles. This high quality was necessary for them to be utilized in applications,” the academy said.

Bawendi was awakened in Cambridge, Mass., by the call telling him he had won. He described himself as “very surprised, sleepy, shocked, unexpected and very honored.”

News of the winners was actually no surprise to some, because the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences sent out a news release by mistake to various media early Wednesday announcing the new laureates. A spokeswoman for the academy tried to walk back the release by saying that no final decision had been made at the time it was issued.

Nobel Prize winners Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman harnessed messenger RNA, an advance that led to the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines.

“This is very unfortunate,” Hans Ellegren, the secretary general of the academy, said at the news conference where the award was finally announced. “We do regret what happened.”

The Swedish academy, which awards the physics, chemistry and economics prizes, asks for nominations a year in advance from university professors and other scholars around the world.

A committee for each prize discusses candidates in meetings throughout the year. The committee then presents one or more proposals to the full academy for a vote. The deliberations are kept confidential for 50 years.

Bawendi said no one called him before the award was announced to tell him about the news release, and so he was surprised to receive the academy’s middle-of-the-night call.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

He said he was not thinking about the possible applications of his work when he started researching quantum dots. “The motivation really is the basic science — a basic understanding, the curiosity of ‘how does the world work?’ And that’s what drives scientists and academic scientists to do what they do,” he said.

Brus said he didn’t pick up the phone when the early-morning call came to notify him.

“It was ringing during the night, but I didn’t answer it because I’m trying to get some sleep, basically,” he told the Associated Press. He finally saw the news online when he got up about 6 a.m.

The most important things we know about the cosmos were discovered in the mountains above Los Angeles. ‘You don’t just throw away a historic place,’ says one of the volunteers trying to save it.

“I certainly was not expecting this,” Brus said.

The practical applications of quantum dots, such as creating the colors in flat-screen TVs, are something that he was hoping for when he started the work decades ago, he said.

“Basic research is extremely hard to predict exactly how it’s going to work out,” Brus said. “It’s more for the knowledge base than it is for the actual materials. But in this case, it’s both.”

Last year, Americans Carolyn R. Bertozzi and K. Barry Sharpless and Danish scientist Morten Meldal were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for developing a way of “snapping molecules together” that can be used to explore cells, map DNA and design drugs able to target diseases such as cancer more precisely.

Americans need science to sustain democracy and progress. The alternative is to follow the path of the Soviet Union: sidelining experts and sacrificing lives.

The Nobel announcements continue with the literature prize Thursday. The Nobel Peace Prize will be announced Friday and the economics award Monday.

The prizes carry a cash award of 11 million Swedish kronor ($1 million). The money comes from a bequest left by the prize’s creator, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, who died in 1896.