Commentary: MLB players union finds representing Astros as well as opposing players isn’t easy

Tony Clark was hoarse. It had been 37 days since Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred issued the report that branded the Houston Astros as cheaters, more than enough time for the baseball world to digest it, debate it, and move on.

Instead, the sparks of disgust erupted into an inferno of outrage. Instead of letting the fire burn out, Manfred and the Astros tossed log after log onto the blaze.

This metaphor is exhausted. So is Clark’s voice. As the executive director of the players union, he meets with every team during spring training. On Wednesday, he held his first meeting this spring, with the players of the New York Mets.

Clark might have to talk about the report for another month, every time he enters a roomful of players angry that the Astros’ players cheated and got away with it.

On the day of the Dodgers’ first full-squad workout, players were continually asked about the Astros’ sign-stealing scandal and accompanying fallout.

The Astros lost their manager, general manager, and a few draft picks. The Astros’ players lost nothing: no suspensions and no forfeiture of the World Series championship they won in 2017, the year Manfred ruled they had cheated.

Wherever a television camera has ventured in spring training, anger has followed, from some of the game’s brightest stars: Mike Trout, Cody Bellinger, Justin Turner, Kris Bryant, Aaron Judge, Giancarlo Stanton.

Clark asks not for sympathy. But he is the guy left to explain to every team why Astros’ players were not punished.

“The rules on the books with regard to sign stealing clearly lay out that clubs and club personnel can be disciplined, and not players,” Clark said.

Before Manfred issued his report, did the union’s executive board — the elected player leadership — discuss whether players ought to be disciplined anyway?

“This wasn’t a situation where there was a conversation,” Clark said. “That’s what the rules stated. In order for that consideration to be made going forward, there’s going to have to be a change or an amendment to the rules.”

The accusatory questions directed at MLB commissioner Rob Manfred painted a picture of a sport that lost the trust of not only the public, but also its players.

Manfred might have explained that in his report, perhaps this way: Players were granted immunity, because we needed their testimony to get to the truth, and because our rules did not permit player discipline in this area. We look forward to working with the union to strengthen those rules.

Instead, over nine pages in which the word “immunity” never appeared but “transparency” did, Manfred wrote that the Astros’ players would not be disciplined because it would have been “difficult and impractical” — difficult to determine the degree of responsibility among individual players, impractical because so many of those players by now had joined other teams.

Clark must balance the wishes of Astros’ players against the wishes of players who hate the Astros. He could survey all the players, on a secret ballot, about whether the Astros should be stripped of their title. If an overwhelming majority voted yes, he could challenge Manfred to do it.

But why risk fracturing his membership with collective bargaining set to take place next year, when Clark will need a unified front more than ever? Better to look ahead, toward preventing another scandal rather than continuing to argue about this one.

“The player voice here is going to be dictating the best way for us to move forward,” Clark said, “both in the use of technology on and off the field, and with regard to the integrity of the game in general.”

What players want, Clark said, is continued access to video during games, using customized software that would allow a hitter to review his previous at-bats, with the video clips not starting until after the catcher has flashed the signs. That said, Clark indicated players are in favor of limitations on video.

“Guys want the replay room removed,” he said. “Guys want to talk about replay in general. Guys want to talk about removal of the live feed. Guys want to talk about removal of cameras, standardization of cameras in each of the ballparks, and they want to know where each of those cameras are and what each of those cameras do. They also want access to the information the cameras are providing, both on individual players and as a group.

“And they want to talk about a form of discipline associated with the particular nuances of this issue.”

The Houston Astros sign-stealing scandal has been a major topic of conversation at spring training. It’s been tough to keep up, but these memes ought to help.

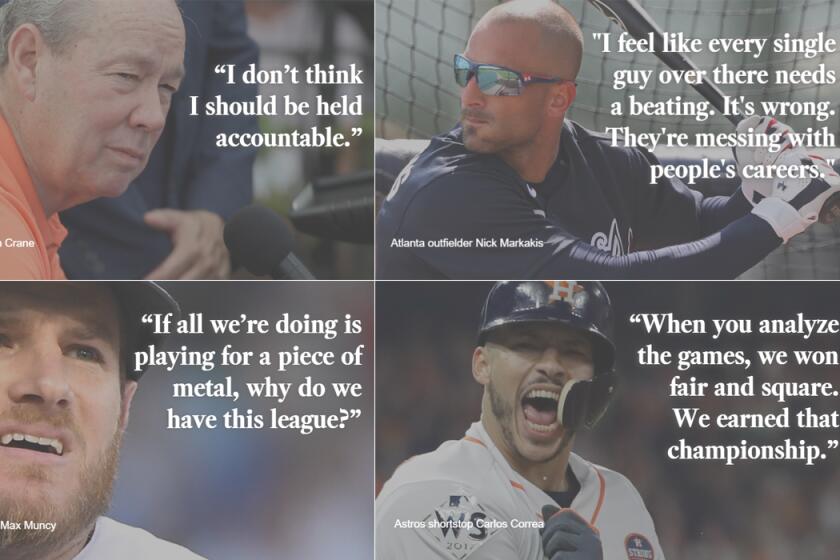

Manfred has said public shaming might be discipline enough for the Astros, which presumes they can be shamed. But their owner, Jim Crane, said that he did not believe he should be held accountable, and that the sign stealing might not have had an impact. Their shortstop, Carlos Correa, said the Astros won the World Series “fair and square.”

None of those comments quieted the storm. Neither did Manfred dismissing the World Series championship trophy as “a piece of metal,” a remark for which he later apologized.

On the other end of the telephone, Clark still sounded hoarse. Does he believe the anger the last two weeks was a response to what the Astros did by stealing signs, or to how the commissioner and the Astros have dealt with it?

Clark chuckled. He paused, for nine long seconds. He eventually offered an indirect answer, but the chuckle and the long pause spoke volumes.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.