His Lahaina restaurant was a Dodgers paradise. He lost it but says ‘I feel blessed’

LAHAINA, Hawaii — In March, my wife and I spent three days in Lahaina, staying two blocks off the now-decimated Front Street. On our first day, arriving after dark and tired from a long flight, we walked a short distance to a nearby Italian restaurant, Penne Pasta, for a late dinner.

As we relaxed, four shelves in a corner caught my eye. They were filled with bobbleheads, and only of Dodgers.

About five dozen of them.

As a lifelong Dodgers fan and Brooklyn native who saw one game in Ebbets Field when I was 7, my curiosity was piqued. I looked around. I was bowled over. Two-thousand-five-hundred miles west of Dodger Stadium was a mother lode of Dodgers memorabilia.

At my request, the smiling chef-owner, Juan Gomez, emerged from the kitchen, chatting with customers — locals and tourists alike — and joined our table. We returned each of the next two days.

As we talked over three meals, Gomez happily told me about the restaurant and of rooting for the Dodgers.

Penne Pasta and everything in it were destroyed when Lahaina was devastated by the monstrous, fast-moving wildfire on Aug. 8 that killed more than 100 people while leaving several hundred missing.

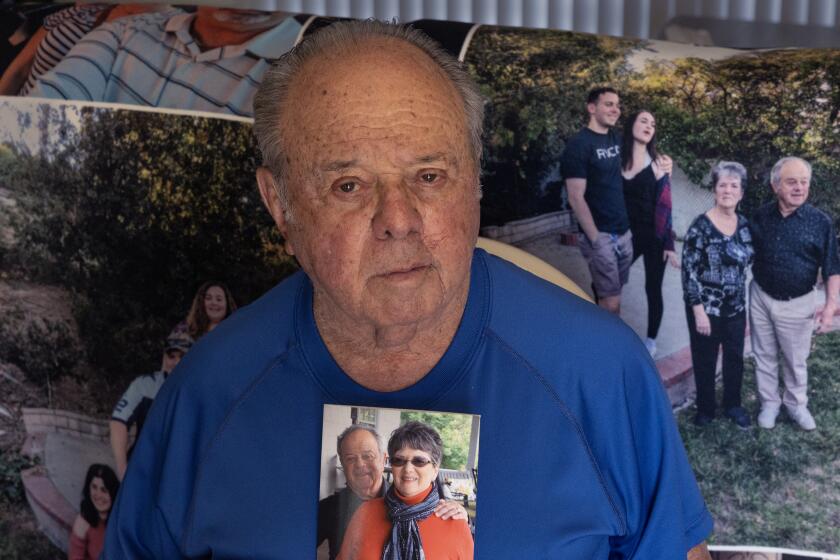

Gomez, 49, had worked nearly half his life at this casual, family-friendly restaurant located on a quiet side street a block and a half from the buzz of touristy Front Street, Lahaina’s main drag.

Starting as a dishwasher at the trattoria in 2001, Gomez moved up the eatery’s echelon — from cook to manager to chef to partner — and he learned the art of Italian cuisine, which he said he knew nothing about previously.

With 50 doubles, the Dodgers’ Freddie Freeman could challenge the MLB all-time single-season record held by an unknown nicknamed the Earl of Doublin’.

That all changed thanks to Gomez’s diligence and restaurant owner Mark Ellman — “my mentor and friend” — who not only taught the apt student the intricacies of being a chef but also how to run a restaurant.

“In 2009, I had started to realize that I wanted to work for myself and have my own restaurant. I brought it up with Mark and told him, ‘When the time comes, I’m going to do it,’” Gomez recalled.

Ellman, who died in February at 67, was a famed Hawaiian chef and restaurant owner. He sold Penne Pasta to Gomez in 2010, financing the loan on his own.

Gomez, who had become a U.S. citizen in 2006, continued to be the chef, developing specialties with his unique touches, such as baked ziti — “our No. 1 seller” — penne puttanesca and chicken piccata, putting in 70 to 80 hours weekly in the kitchen and dining area.

But not every week.

As much as he loved running the restaurant, consisting of about 10 tables inside and on a patio, Gomez also loved the Dodgers. He would take a week or two off each year and fly to Los Angeles, timing those visits with Dodgers home games and attending several of them.

A native of the Mexican state of Jalisco, Gomez became an enormous Dodgers fan thanks to his countryman Fernando Valenzuela.

In 1981, when Gomez was 7, Valenzuela, then 20, captured the attention and hearts of baseball fans in Mexico and the United States. The left-handed hurler from Sonora, whose eyes would look to the heavens before every pitch, helped the Dodgers win the pennant and, for the first time in 16 seasons, the World Series. Valenzuela received the National League Cy Young and rookie of the year, the lone player to win both in the same year.

The only games televised where Gomez lived were when Valenzuela took the mound. And he tried to watch every one of them.

In 1991, when he was 17, Gomez moved to Montebello, where he had completed the ninth grade. He did not return to school. Among his jobs was painting houses. Seeking a better life, he moved to Maui in 1995. But the hours were longer as he washed dishes at another restaurant and picked pineapples.

RJ Peete, the son of former NFL quarterback Rodney Peete and actress Holly Robinson-Peete, hasn’t let autism stop him from living his dream with the Dodgers.

His love for the Dodgers never waned and over the years, he began accumulating what would become a prodigious collection of Dodgers collectibles and memorabilia. They included multiple bobbleheads of Valenzuela, Clayton Kershaw, Vin Scully and Tommy Lasorda and others of less famous Dodgers, such as Cody Bellinger, Jeff Kent, Adrian Gonzalez, Yasiel Puig, Zack Greinke and Joc Pederson. And one of Ecuadorian-born Jaime Jarrín, the club’s longtime Spanish-language broadcaster who retired at the end of the 2022 season after 64 seasons, only three fewer than Scully.

Gomez’s first bobblehead was Paul Lo Duca, a Dodgers catcher from 1998 to 2004. It was a giveaway at Dodger Stadium. But most of Gomez’s collection came as gifts from customers who live on the mainland and would bring them on return visits.

Inside a glass case at Penne Pasta was an eclectic collection: a color photo of Sandy Koufax, a Ron Cey glove and an Austin Barnes 2020 World Series jersey. All were autographed. A giant color photo — perhaps four by eight feet — of a packed, opening-day crowd at Dodger Stadium was reproduced on one wall. All those items were given to Gomez by a friend who worked for the Dodgers.

Erwin Goldbloom still is reeling over the loss of his wife, Linda Goldbloom, who was killed after a foul ball hit her in the head at Dodger Stadium five years ago.

Inside Penne Pasta, every Dodgers game was shown on a huge TV.

During phone interviews since the fire, Gomez has shared the great pain of the disaster.

He lost the restaurant and all his memorabilia — Mark Langill, Dodgers team historian, said he will replace much of it, as “one collector to another” — in the catastrophic blaze, but Gomez knows that his problems are infinitesimal compared to those of others afflicted in the vast tragedy in West Maui.

The aura of death and destruction and shattered hopes will hang over this once-major whaling village for years to come.

“It is very frustrating that the dreams of so many people who worked hard for so many years to build their house, their business, through sweat and tears, and to get something for their family, and in one night ...” Gomez said, his voice trailing off.

“One part of me is gone, but I haven’t lost any family members, and all 10 of our employees, including my sister, Martha Yepez, are accounted for and are safe. I have lost some friends who were customers who became friends. Some of them have died. Some of them are still missing.”

A.J. Wilson, who worked in various capacities for Gomez during the last decade, said in March that Gomez “takes care of me. He’s like my dad.”

They thought the grass fire was contained, but wind conditions were still extreme. Now the decision to pull firefighters away shortly before the Maui fire reignited has become a flashpoint, as questions mount over whether more could have been done to stave off the destruction.

Like the other employees, he is now out of a job.

The restaurant was closed the day of the fire because a camera system at his home showed that Penne Pasta’s power had gone out early that morning, so Gomez and his wife, Esperanza, went there.

“We were trying to keep the food cold by running our generators,” he said.

That evening, with the Gomezes still in the restaurant, the fire quickly closed in.

“It was very windy, and everything started to get black,” he said. “I knew it was a big fire because you could see black smoke that was super, super thick. And you could hear the explosions, either of cars or propane tanks, and they were super loud. Police cars started driving by and broadcasting, ‘You have to go! You have to go!’”

The Gomezes left quickly and avoided getting caught in the large traffic jam of people fleeing. Their home, about a dozen miles away from Lahaina, escaped the fire.

Gomez’s two daughters, who had been visiting from Jalisco, were safe, having returned home a few days before the blaze.

As Maui hotel rooms sit empty after the deadly Hawaii wildfire that devastated Lahaina, some are sounding economic alarms, asking tourists to return.

Gomez has not been allowed to return to where the restaurant used to stand. Security forces initially kept people away as cadaver dogs searched for remains. But from photographs and videos he knows there is nothing left.

For years, Gomez never missed watching a Dodgers game. But he has seen only bits and pieces of games since the blaze. There are far more important things to weigh.

It is unclear what the future holds for the Gomezes.

“This is the longest that I haven’t been working in 28 years. It’s still too early to decide what we want to do,” he said, “and it’s not 100% our decision.”

Insurance issues must be resolved, as he did not own the two-story, wood-frame building that housed the restaurant.

“It’s up to the owners,” Gomez said. “Perhaps we’ll have to relocate. At this point, I don’t have a plan or a decision. I will just go with the flow. I feel calm. I feel blessed. We still have a roof. So many people don’t have anything to go back to. We just have to keep going with our lives. We have to rebuild or move on.”

Leader, of Carmel Valley, is a former editor for the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.